At the end of your life, if someone asks you what it all meant, what will you say? It’s a question that can’t be answered until after you’ve turned the final page, but there is an idea at least that death brings clarity, rendering all things simple from a strange perspective of subjective objectivity. This is the central idea behind Hirokazu Koreeda’s meta existential fantasy After Life (ワンダフルライフ, Wonderful Life) in which the recently deceased are given seven days’ grace in order to decide on their most precious memory so that a small collection of clerks working in an old-fashioned government building can “recreate” it through the medium of cinema, allowing a departing soul to take refuge in a single memory preserved in eternity.

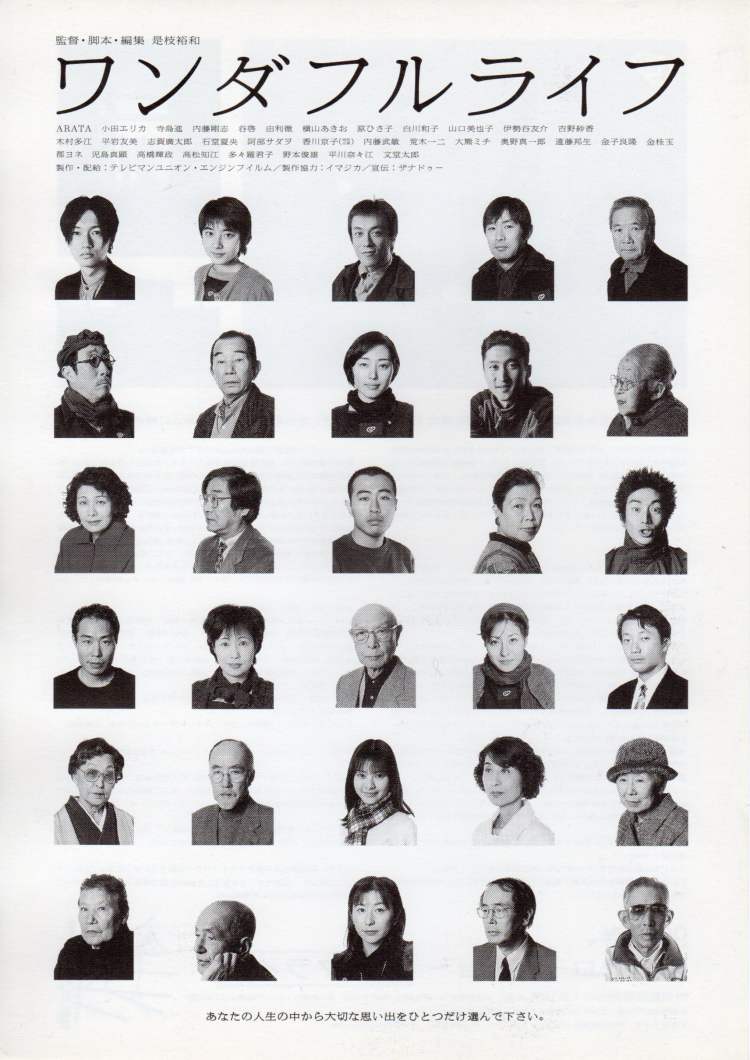

At the end of your life, if someone asks you what it all meant, what will you say? It’s a question that can’t be answered until after you’ve turned the final page, but there is an idea at least that death brings clarity, rendering all things simple from a strange perspective of subjective objectivity. This is the central idea behind Hirokazu Koreeda’s meta existential fantasy After Life (ワンダフルライフ, Wonderful Life) in which the recently deceased are given seven days’ grace in order to decide on their most precious memory so that a small collection of clerks working in an old-fashioned government building can “recreate” it through the medium of cinema, allowing a departing soul to take refuge in a single memory preserved in eternity.

Heaven’s waiting room, as it turns out, is apparently located inside the ghost of the Japanese studio system. The recently deceased give their names at the door and patiently wait for their turn with their allotted case manager whose job it is to offer after life counselling designed to bring them to the point of boiling their existence down to the single moment which defines it within the arbitrary three day time limit which gives the crew the time to put their memories into pre-production complete with old-fashioned stage sets and studio-era special effects.

The purpose of all of this is not is exactly clear, though a clue is perhaps offered when we discover that the clerks are able to order VHS tapes of the entirety of their subjects’ lives in the event that they are struggling to think of relevant moments in an existence which seems to have disappointed them. The point is not so much the literal truth of the memory, be it accurate or not, but its sensation and the transience of feeling which is then re-experienced through the medium of cinema, captured in celluloid as momentary permanence.

Consequently, the chosen moments are necessarily often ones of stillness which promise the kind of peace and serenity one is supposed to find in death. The moments are ones of silent togetherness, of natural beauty, of childish innocence, or unbridled joy but is each is perhaps the key to unlocking the enigma of a life and as such is a solution which points towards a question. One older gentleman, Watanabe (Taketoshi Naito), finds himself unable to choose. He views his life as the epitome of mediocrity and can find nothing in it that seems worthy of “eternity”. Watching the videotapes of his life, he sees himself as a young man vowing to make a mark and is desperate to find some evidence that he lived but like many does not find it. His life was happy by virtue of being not unhappy for all that it was perhaps unfulfilled but only through communing with himself after death is he able to reclaim the memory of his late wife (Kyoko Kagawa) with whom he never quite bonded in mild jealousy of her lingering attachment to her first love who fell in war.

This being a film from 1998 and mostly featuring those in their 70s and above, the war looms large from painful battlefield memories of fear and starvation to unexpected reunions and the joy of simple pleasures found even in the midst of hardship. The clerks who died young may look on in envy of Watanabe’s “ordinary” life in the knowledge of all they were denied, while others mourn for a future they will never see. Yet there are shorter sad stories here too from a high school girl (Sayaka Yoshino) whose original choice of a day out at Disneyland is deemed too prosaic, to a middle-aged bar hostess (Kazuko Shirakawa) reminiscing about an old lover who let her down, and a rebellious young punk (Yusuke Iseya) who flat out refuses to choose because he feels that is the best way to accept responsibility. Forced into a reconsideration of his own life, even a clerk is eventually moved by the realisation that even if he had previously believed his existence devoid of meaningful moments he has achieved something by featuring in those of others and is therefore also a meaningful part of a considered whole.

Making the most of his documentary background, interspersing “genuine” memories among the imagined, Koreeda’s heavenly fantasy is one firmly tied to the ground where seasons still pass, time still flows, and the relentlessly efficient march of bureaucracy continues on apace undaunted by the presence of death. Death may give life meaning, but it’s living that’s the prize in all of its glorious complexity filled with both beauty and sadness but always with light even in the darkest corners.

After Life screened as part of an ongoing Koreeda retrospective currently running at BFI Southbank.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

1 comment