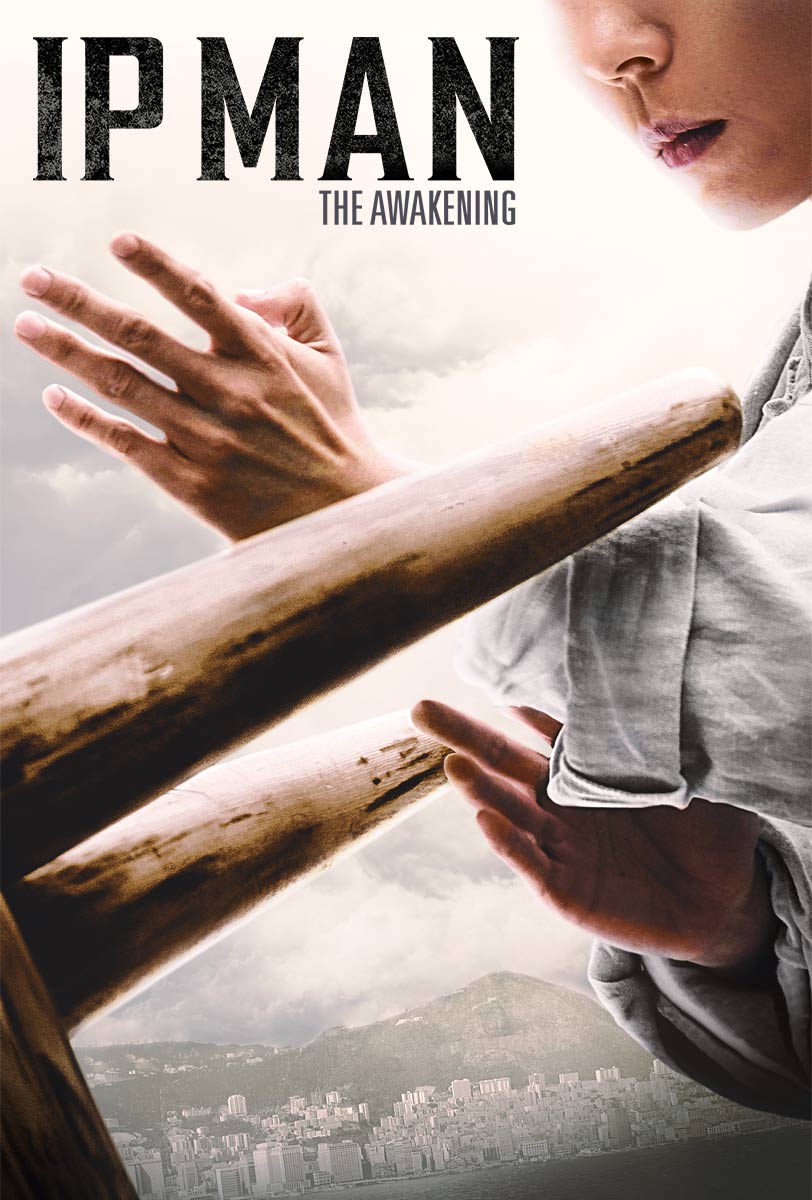

“Someone must stand up to injustice!” according to the young Ip Man (Miu Tse) newly arrived in Hong Kong and witnessing the abuses of colonialism first hand. A kind of origin story, the latest outing for the legendary hero, Ip Man: Awakening (叶问宗师觉醒, Yè Wèn zōngshī juéxǐng), has its degree of political awkwardness but essentially finds the young master coming to an understanding of the purpose of martial arts while realising that sometimes you have to play the long game and not every problem can be solved with Wing Chun alone.

This is something he discovers after stepping in to protect a young woman and her mother who are being hassled by muggers on a street car. Evidently, the thieves seem to have been emboldened and assume themselves to be under no threat from the passengers, driver, or indeed law enforcement and were not expecting to be challenged. Unfortunately, however, Ip Man’s gallant defence of the two women only brings him a whole mess of trouble in a new city in irritating a local gang who are it seems linked to arch villain Stark. A corrupt British official, Stark has been colluding with local police to run a lucrative people trafficking operation though even they are becoming worried by Stark’s increasing arrogance brazenly snatching young women off the street to sell abroad.

According to Stark, there are only two kinds of people, cheap and expensive, which bears out his imperialist worldview. Yet, Ip Man himself is perhaps awkwardly positioned as a Mainlander fighting colonial oppression in Hong Kong. According to his apathetic friend Feng perhaps it doesn’t matter who’s in charge because it’s all pretty much the same, but to Ip Man it does seem to matter though given the current situation between the two territories his words cannot help but seem ironic if not directly subversive. He seems to suggest that men like Feng, who later tries to appease Stark who has kidnapped his younger sister Chan, have enabled their own oppression and only by rising up against it can they be free which is it has to be said a series of mixed messages only finally resolved by Ip Man’s reminder that “We are all Chinese” during his final fight battling his way towards Stark.

Nevertheless, the battleground that develops is located firmly within the realms of marital arts with a stand-off between the Chinese Wing Chun and the almost forgotten British fighting style Bartitsu. Not content with subjugating Hong Kong, the British apparently have to prove their superiority even over this sacred territory only they’re as duplicitous and immoral about it as they are over everything else. Even so, Ip Man is able to overcome their blatant attempts to cheat through manipulating Feng and proves that Wing Chun is the best after all while Feng pays a heavy price for his complicity but is later forgiven having learned his lesson.

What Ip Man learns is that as his teacher points out righteousness requires both wisdom and resources. He can’t expect to solve all the world’s problems by wading in his with his fists and sometimes doing the right thing is going to land him in a world of trouble and complication but even so he has to do it because a “world in which asking for justice is wrong would be truly hopeless”. Perhaps more mixed messages, but leaning in to the Ip Man mythos as a man who stands firm in the face of oppression and fights for the rights of those who cannot fight for themselves.

Then again, this is a Mainland film and if was surprising that the spectre of police corruption was raised (it’s the British colonial police after all) the conclusion ensures that the authorities will finally get on the case and put a stop to the human trafficking ring once and for all while clearing out the corrupt imperialists. Ip’s sense of righteousness is well and truly awakened in the knowledge that he and his fists can make a real difference even if lasting change requires a little more finesse. With some nifty if occasionally unpolished action sequences Zhang Zhulin and Li Xijie’s take on the classic Ip Man story makes the most of its meagre budget while positioning Hong Kong veteran Tse Miu as the latest incarnation of the ever popular hero.

Ip Man: The Awakening is released in the US on DVD & blu-ray courtesy of Well Go USA on June 21.

Trailer (English subtitles)