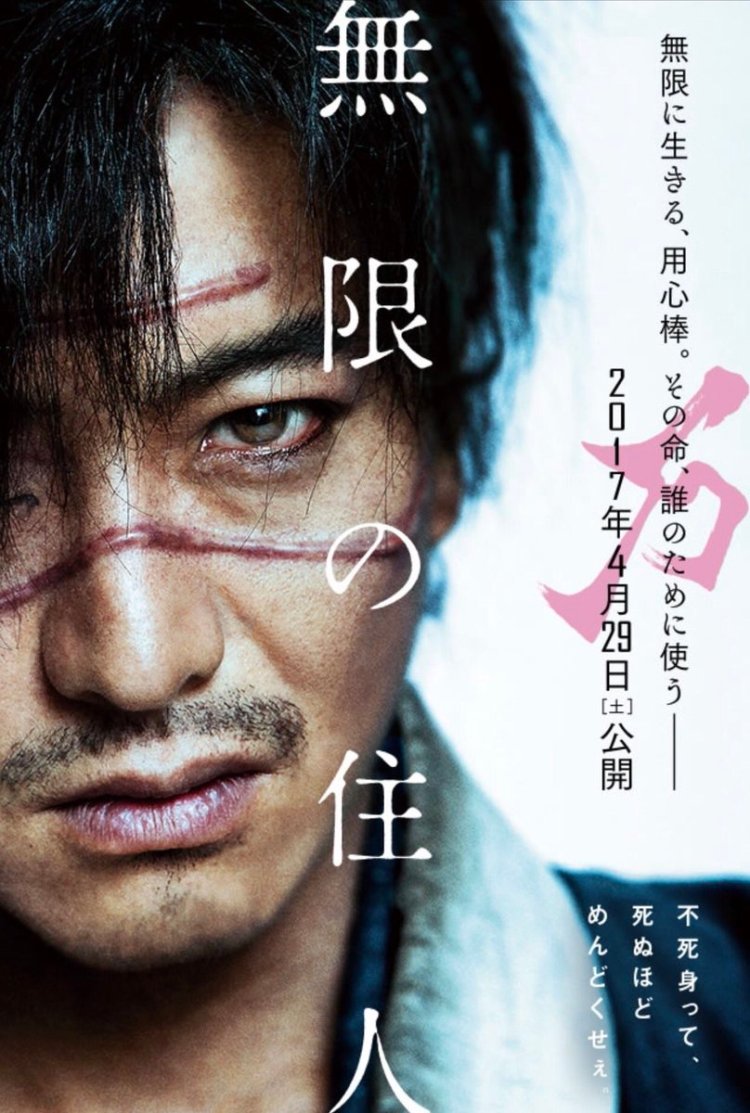

Generally speaking, revenge tends not to go very well in Japanese cinema. It has the tendency to backfire. When you’re immortal, however, perhaps revenge is risk worth taking – then again, it’s not your life your weighing. Takashi Miike is no stranger to the jidaigeki world, though in adapting Hiroaki Samura’s manga Blade of the Immortal (無限の住人, Mugen no Junin) he harks back to the angry, arty samurai films of the late 1960s from Gosha’s Sword of the Beast with which the manga features some minor narrative similarities, to Kobayashi’s melancholy consideration of corrupted honour, and the frantic intensity of Okamoto’s Sword of Doom.

Generally speaking, revenge tends not to go very well in Japanese cinema. It has the tendency to backfire. When you’re immortal, however, perhaps revenge is risk worth taking – then again, it’s not your life your weighing. Takashi Miike is no stranger to the jidaigeki world, though in adapting Hiroaki Samura’s manga Blade of the Immortal (無限の住人, Mugen no Junin) he harks back to the angry, arty samurai films of the late 1960s from Gosha’s Sword of the Beast with which the manga features some minor narrative similarities, to Kobayashi’s melancholy consideration of corrupted honour, and the frantic intensity of Okamoto’s Sword of Doom.

The film opens in black and white as a disgraced samurai, Manji (Takuya Kimura), tries to protect his younger sister, Machi (Hana Sugisaki), who has gone mad through grief only to see her murdered by a bounty hunter. Manji enters a state of furious, mindless killing which leaves the bounty hunter’s vast crowd of henchmen lying dead and Manji mortally wounded. Consumed by guilt and having lost the sister who was his sole reason for living, Manji longs for death but a mysterious old woman who calls herself Yaobikuni (Yoko Yamamoto) has other ideas and curses Manji to a life of eternal suffering by means of sacred bloodworms which give him the power of infinite, near instant healing.

Fifty years later, the land is at peace under the Tokugawa Shogunate but peaceful times are dull for warriors. The Itto-ryu school of swordsmanship has a mission – to take over all of the nation’s martial arts facilities and restore power to the sword. They have no honour or ideology save that of kill or be killed and are content to use any and all weapons which come to hand. A young girl, Rin (Yoko Yamamoto), is a daughter of one of these schools and has her eyes set on becoming a top swordswoman herself but when the Itto-ryu show up at her door, Rin’s father’s training proves worthless as he’s cut down with one blow while the gang kidnap Rin’s mother. The Itto-ryu’s sole concession to morality is in letting Rin alone, seeing as it’s “vulgar” to toy with children.

Rin vows revenge on the Itto-ryu’s leader, Anotsu (Sota Fukushi), at which point she runs into Yaobikuni who recommends she track down Manji and hire him as a bodyguard. Fifty years of immortality have turned Manji into an isolated, embittered wastrel with rusty swordskills but Rin’s uncanny resemblance to Machi eventually begins to move his heart. Despite generating a master/pupil, big brother/little sister relationship, Manji fails to teach Rin very much of consequence that might assist her in her plan to avenge her family, leaving her a vulnerable young woman beset by enemies and random thugs, and eventually caught up in a government conspiracy. The irony of Manji’s life is that he’s just not very good at the art of protection and all of his attempts to do something good usually provoke an even bigger crisis, in this case leaving his new little sister open to exactly the same fate as the one he failed to save for much the same reasons. Apparently, Manji has learned little during his extended lifetime except how to brood and glare resentfully at the world.

It turns out being immortal is kind of a drag. Manji wants to die because he can’t cope with the burden of his guilt, but another similarly cursed man he meets has lived much longer and lost far more, becoming tired of the business of of living. Manji’s existence has lost all meaning, but as he puts it to another world weary warrior who shares his brotherly grief, he’s not the only hero of a sad story. Rin’s need for vengeance gives him a purpose again – not just in the literal revenge, but in being the protector (though one could argue this is less positive than it sounds and might explain why he fails to teach Rin anything very useful, even if it doesn’t explain why she also forgets all her father’s teachings).

Rin remains conflicted over her mission of revenge, confessing to a similarly conflicted assassin that she agrees killing is wrong but that right and wrong no longer matter when it comes to people you love. A dangerous and dubious assertion, but it does bear out the more positive message that love, or at least learning to live for others, can be a transformative force for good as Manji allows himself to resume his role as the big brother despite his past failings. Violent and visceral, if also humorous, Blade of the Immortal is, oddly enough, a story of love but also of cyclical paths of violence and revenge, and of the general muddiness of assigning the moral high ground to those engaged in a quest for retribution.

Blade of the Immortal was screened as part of the BFI London Film Festival 2017 and will be released in UK cinemas courtesy of Arrow Entertainment on 8th December.

International trailer (English subtitles/captions)

Chinese independent cinema has been in the ascendent recently, becoming a regular presence at high profile festivals. This year’s selection of films from the mainland includes two very different animated features alongside comedy, action and arthouse.

Chinese independent cinema has been in the ascendent recently, becoming a regular presence at high profile festivals. This year’s selection of films from the mainland includes two very different animated features alongside comedy, action and arthouse. Two giants of Hong Kong cinema return – celebrated filmmaker Ann Hui with a tale of love and resistance, and legendary cinematographer Christopher Doyle shooting a noir fairytale for Jenny Suen.

Two giants of Hong Kong cinema return – celebrated filmmaker Ann Hui with a tale of love and resistance, and legendary cinematographer Christopher Doyle shooting a noir fairytale for Jenny Suen. Japanese entries are dominated by animation but there’s also space for Takashi Miike’s manga adaptation Blade of the Immortal which headlines the Thrill section, as well as Naoko Ogigami’s latest Close-Knit, and the recent 4K restoration of 60s avant-garde masterpiece Funeral Parade of Roses.

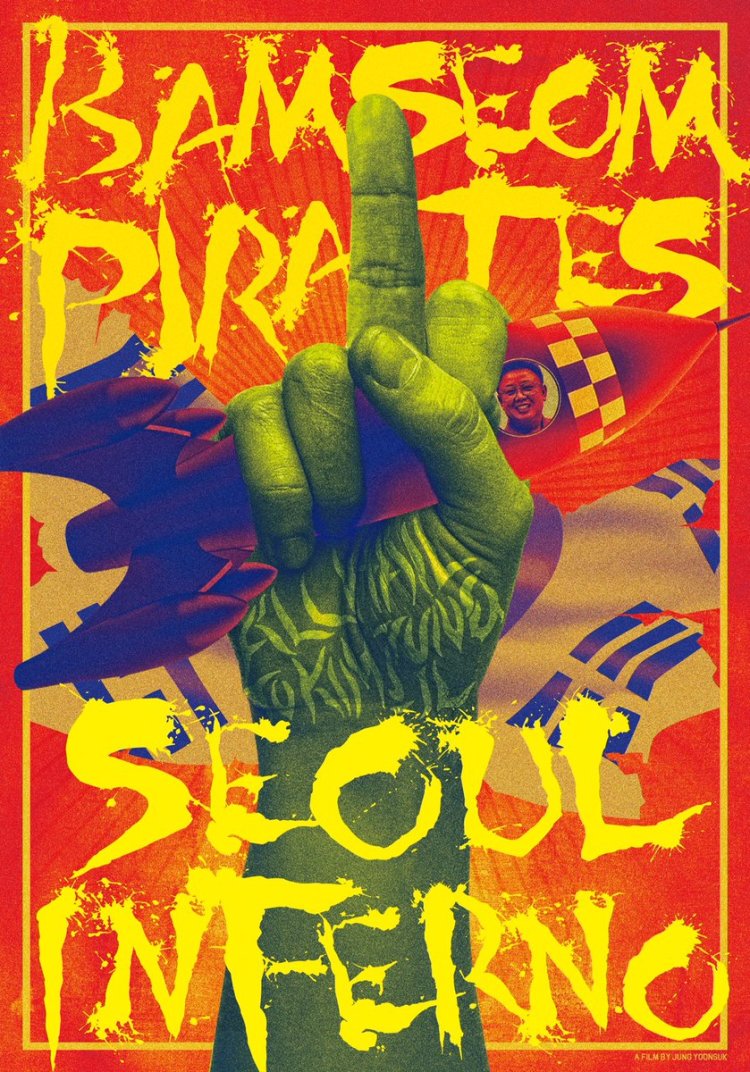

Japanese entries are dominated by animation but there’s also space for Takashi Miike’s manga adaptation Blade of the Immortal which headlines the Thrill section, as well as Naoko Ogigami’s latest Close-Knit, and the recent 4K restoration of 60s avant-garde masterpiece Funeral Parade of Roses. Everything you’d expect from Korea from anarchic documentary to violent procedural and the annual return of Hong Sang-soo.

Everything you’d expect from Korea from anarchic documentary to violent procedural and the annual return of Hong Sang-soo. Thailand’s two entries feature youth looking forward and age looking back.

Thailand’s two entries feature youth looking forward and age looking back.

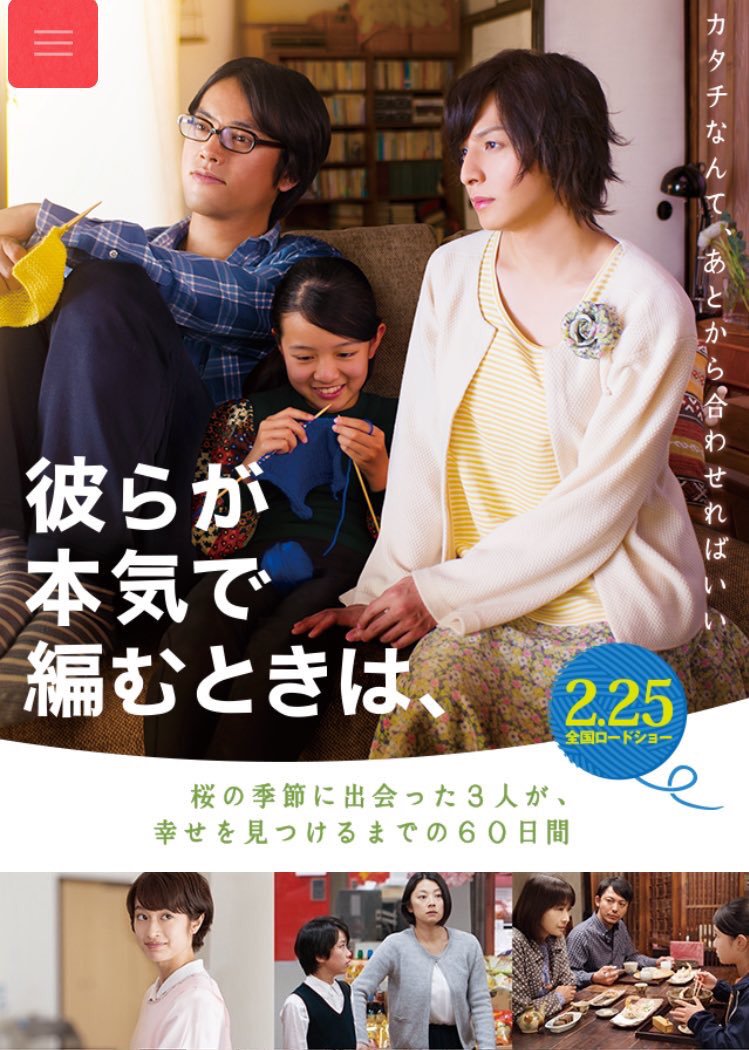

While studying in the US, director Naoko Ogigami encountered people from all walks of life but on her return to Japan was immediately struck by the invisibility of the LGBT community and particularly that of transgender people. Close-Knit (彼らが本気で編むときは, Karera ga Honki de Amu Toki wa) is her response to a still prevalent social conservatism which sometimes gives rise to fear, discrimination and prejudice. Moving away from the quirkier sides of her previous work, Ogigami nevertheless opts for a gentle, warm approach to this potentially heavy subject matter, preferring to focus on positivity rather than dwell on suffering.

While studying in the US, director Naoko Ogigami encountered people from all walks of life but on her return to Japan was immediately struck by the invisibility of the LGBT community and particularly that of transgender people. Close-Knit (彼らが本気で編むときは, Karera ga Honki de Amu Toki wa) is her response to a still prevalent social conservatism which sometimes gives rise to fear, discrimination and prejudice. Moving away from the quirkier sides of her previous work, Ogigami nevertheless opts for a gentle, warm approach to this potentially heavy subject matter, preferring to focus on positivity rather than dwell on suffering.