Can a creator be held legally responsible for what other people might decide to do with their creation? For some, that is the essential question of the trial at the centre of Yusaku Matsumoto’s legal drama Winny, but in speaking more to the present day than the early 2000s in which the real life events took place the film is more concerned with freedom of speech in a society in which established authorities may seek to resist the democratisation of information.

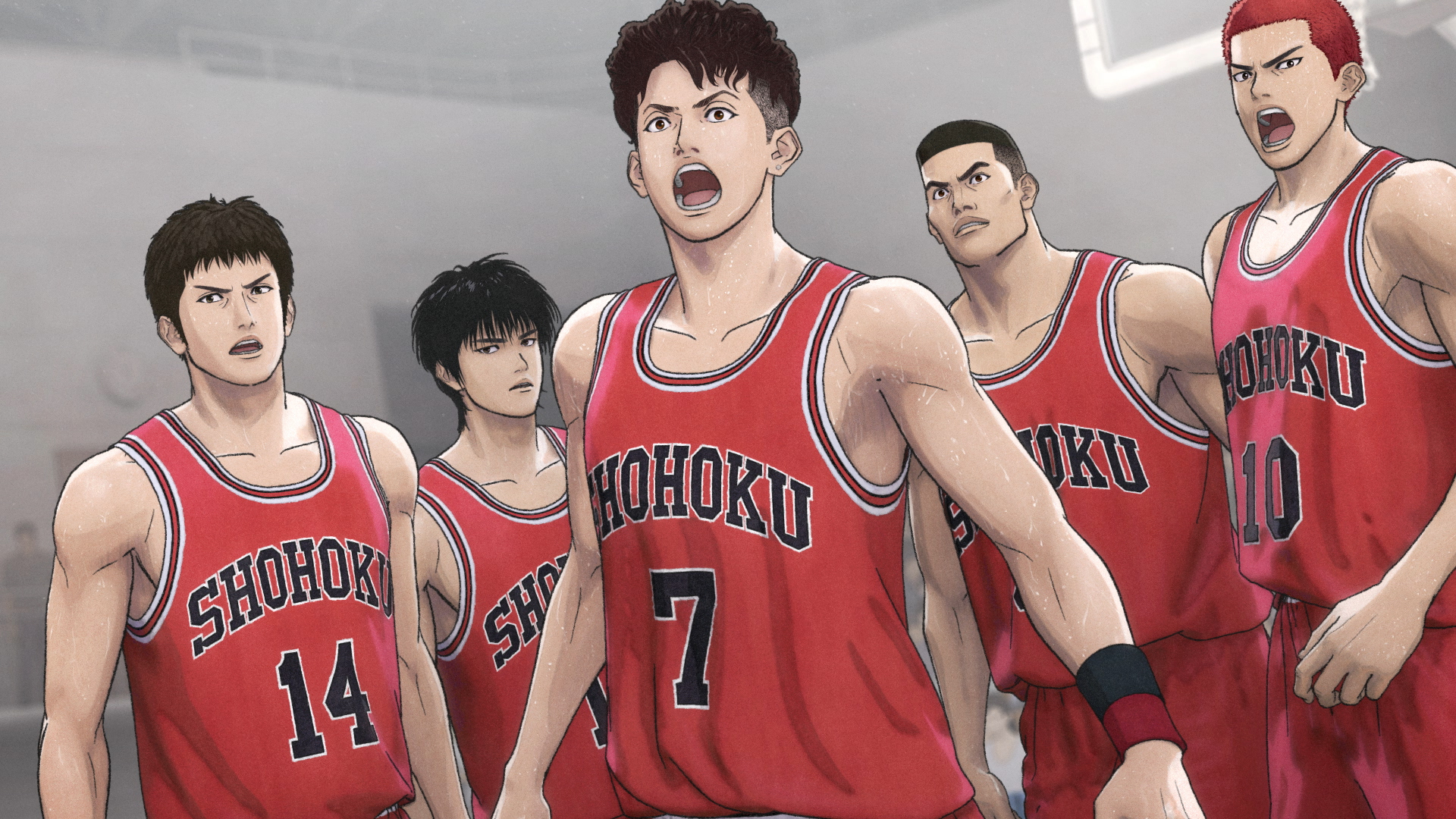

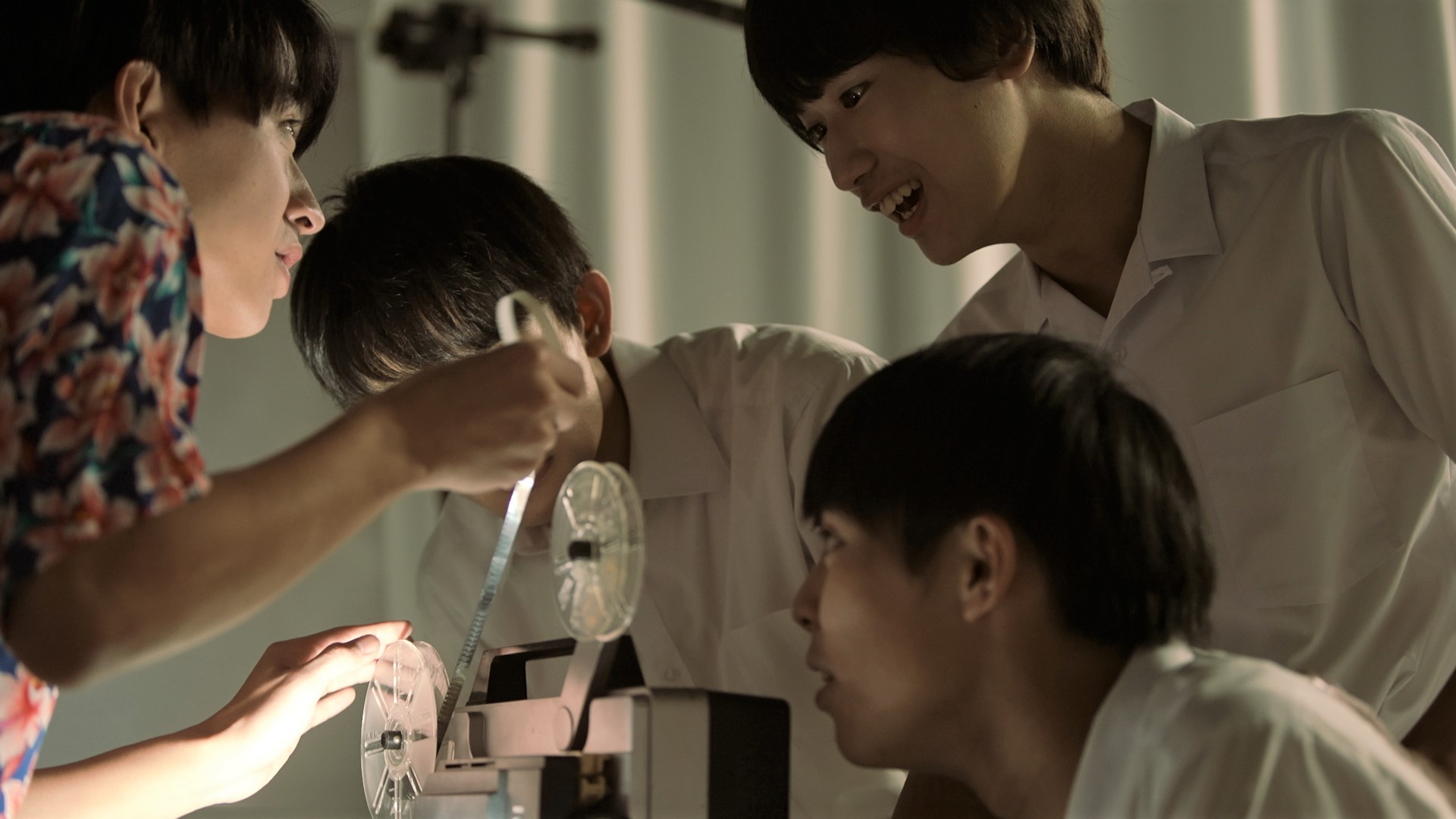

A talking head seen on television at one point suggests that peer-to-peer file sharing programme Winny disrupts the democratic copyright regime, but according to its creator Isamu Kaneko (Masahiro Higashide) the appeal of peer-to-peer is that it is by nature democratic in forging a network of machines on an equal footing. Nevertheless, in November 2003 two people were arrested for using Winny to share copyrighted material and Isamu’s home was searched by the Kyoto police who arrested him for aiding and abetting copyright infringement. He and his lawyers argue that to charge the developer is wrongheaded and irresponsible in that it will necessarily stifle technological advance if developers are worried about prosecution if their work is misused by others while his intention in any case had not been to undermine copyright laws but essentially for technological innovation in and of itself.

Meanwhile, the film devotes much of its running time to a concurrent police corruption scandal in which a lone honest cop is trying to blow a whistle on a secret slush fund founded on fraudulently produced expense receipts. The implication is that the reason the police decided to go after Isamu is that they feared Winny’s potential to expose their own wrongdoing. A member of the police force had apparently used Winny and introduced a vulnerability to the police computer system that allowed confidential data to be leaked, and Winny is indeed later used to publicly disseminate evidence which proves the claims of the whistleblower, Semba (Hidetaka Yoshioka), are true. Semba had previously tried to take his concerns to the press privately but was ignored, the editor simply printed a police press release without investigation unwilling to rock the boat. But a programme like Winny exists outside of the establishment’s control which is why, the film suggests, the police in particular resent it.

A younger officer Semba reproaches at his station gives the excuse that everybody does it and refusing to fill in the false receipts would make it difficult for him to operate in an atmosphere in which corruption has become normalised. Even the police use Winny, a prison guard confiding in Isamu that he’s used the programme to download uncensored pornography while prosecution lawyers conversely attempt to embarrass Isamu by leaking pictures of his porn collection to the press and bringing it up on the stand. “Everybody does it” is not a good defence at the best times aside from being a tacit admission of guilt but reinforces a sense that the police operates from a position of being above the law. A particularly smug officer thinks nothing of perjuring himself on the stand, spluttering and becoming defensive when Isamu’s lawyers expose him in a lie.

Isamu is depicted as a rather naive man whose social awkwardness and childlike innocence leave him vulnerable to manipulation. He’s told to sign documents by the police so he signs them thinking it’s better to be cooperative, taking the advice he’s given when he questions a particular sentence that he can correct it later at face value while assuming that he’ll be able to straighten it all out in court by telling them the truth and that he signed the documents because the police told him to. Meanwhile, he’s almost totally isolated, prevented from talking to friends and family out of a concern that he may use them to conceal evidence.

The film seems to suggest that the stress of his ordeal which lasted several years may have led to his early death at the age of 42 soon after his eventual acquittal. In any case he finds a kindred spirit in his intellectually curious lawyer (Takahiro Miura) who defends him mostly on the basis that the right to innovate must be protected and a developer can not be responsible for the actions of an end user any more than a man who makes knives can be held accountable for a stabbing. Matsumoto captures the sense of wonder Isamu seems to feel for the digital world and has a great deal of sympathy for him as an innocent caught up in a game he doesn’t quite understand while fiercely defending his right to express himself, along with all of our own, without fear no matter what the implications may be.

Winny screens in New York Aug. 2 as part of this year’s JAPAN CUTS.

Original trailer (no subtitles)