There’s something quite poignant in the central themes of Yuzuru Tachikawa’s impassioned jazz anime Blue Giant that these very young men have decided to dedicate themselves to art that even they describe as dying. At their earliest meeting, saxophone player Dai (Yuki Yamada) and pianist Yukinori (Shotaro Mamiya) have a minor disagreement with Yukinori critical of the musicians he was previously playing with describing them as old and their lack of innovation as the reason that the art is decline but according Dai they are also the bearers of its legacy and the ensures of its survival.

It’s an ironic moment at least in that Yukihiro will also later be criticised for a “boring” performance style that plays it safe by concentrating on technical proficiency as opposed to the unbridled anarchy embodied by Dai whose determination to become the world’s greatest jazz player comes off as earnest more than arrogant and a mark of his intense self-belief which also generous and kind rather than jealous or petty. Like many anime heroes, Dai is a young man making the journey to the city and struggling to fulfil his dreams amid its various pressures. On arrival in Tokyo he struggles to find somewhere to practice that is both free of city noise and unlikely to disturb those around him but eventually discovers a small oasis not so different from the riverbank he played by in Sendai.

We’re often reminded that music can be a lonely profession with the implication that Dai has had to sacrifice other areas of his life to dedicate himself to perfecting his art but has achieved surprising skill for only three years experience. Yukinori began playing at four and is envious of an innate talent he doesn’t believe he has or at least to the same extent as Dai. Then again, it may just be that his talent lies elsewhere and he has not yet quite discovered it. Rather than a musical rivalry the pair fall into a mutually beneficial rhythm in which they encourage each other to improve even if as Yukinori said jazz bands aren’t intended to stay together for long and are only ever more like stepping stones to somewhere else.

Their brotherhood is further tested by Dai’s decision to bring in his equally dejected friend Tamada (Amane Okayama) as their drummer despite his never having played the drums before insisting that it would be wrong to frustrate his newfound interest in music. Like the others, Tamada is struggling to rediscover himself after working hard to get into a university in Tokyo but bored by his lectures and disappointed in his fellow students who already seem to be playing the salaryman game. He’s drawn to music in part because of Dai’s love for it and it does seem to be his passion rather than jazz itself that wins over new converts to the supposedly dying art.

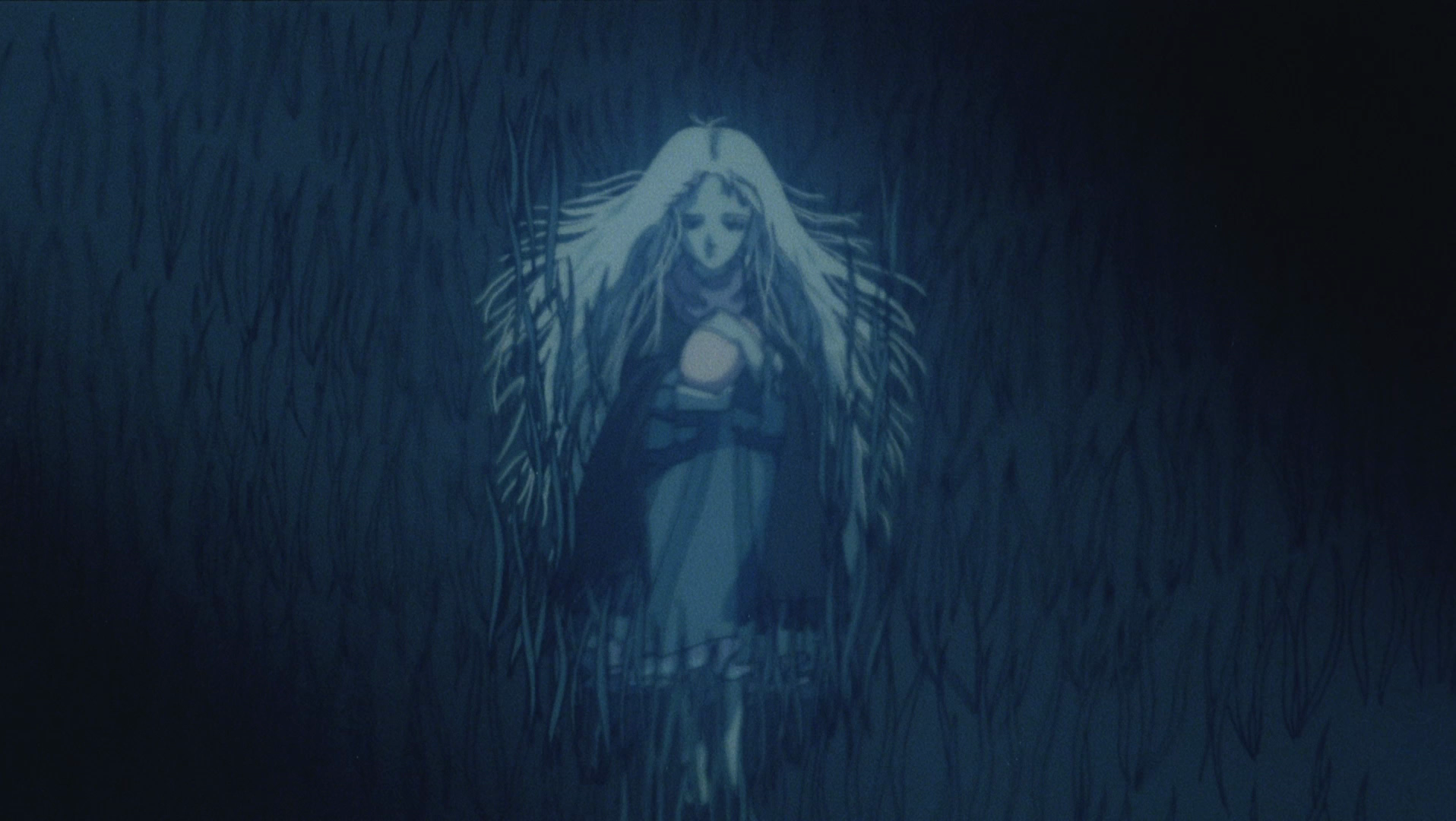

Dai claims to have fallen for jazz because it’s “hot” and “intense” and allows him a means to express himself in freely in a way that becomes almost infectious in its dynamism. Adapted from Shinichi Ishizuka’s manga, the animation emphasises the physicality of performance and the strength and stamina required to become a successful musician though the use of rotoscoping for additional authenticity sometimes seems oddly static and uncanny while largely at odds with the more expressive aesthetics with which the background drama is imbued. Even so Tachikawa echoes the freewheeling nature of the medium through drifting off into abstract, psychedelic sequences that attempt to visualise the transcendent and liberating quality of jazz.

Much of that featured in the film is composed by international jazz pianist Hiromi Uehara which lends a kind of irony to Yukinori’s growing realisation that his piano is the weak link as long he remains unable to unlock his potential and express himself freely through music rather than fallback on the safety and security of tried and tested techniques. In any case, it’s the relationships between them that propel the boys forward towards their respective destinies which may or may not coincide but are as much founded on friendship and solidarity as they are on a love of music.

Blue Giant opens in UK cinemas on 31st January courtesy of Anime Limited.

International trailer (English subtitles)

Images: © Blue Giant Partners