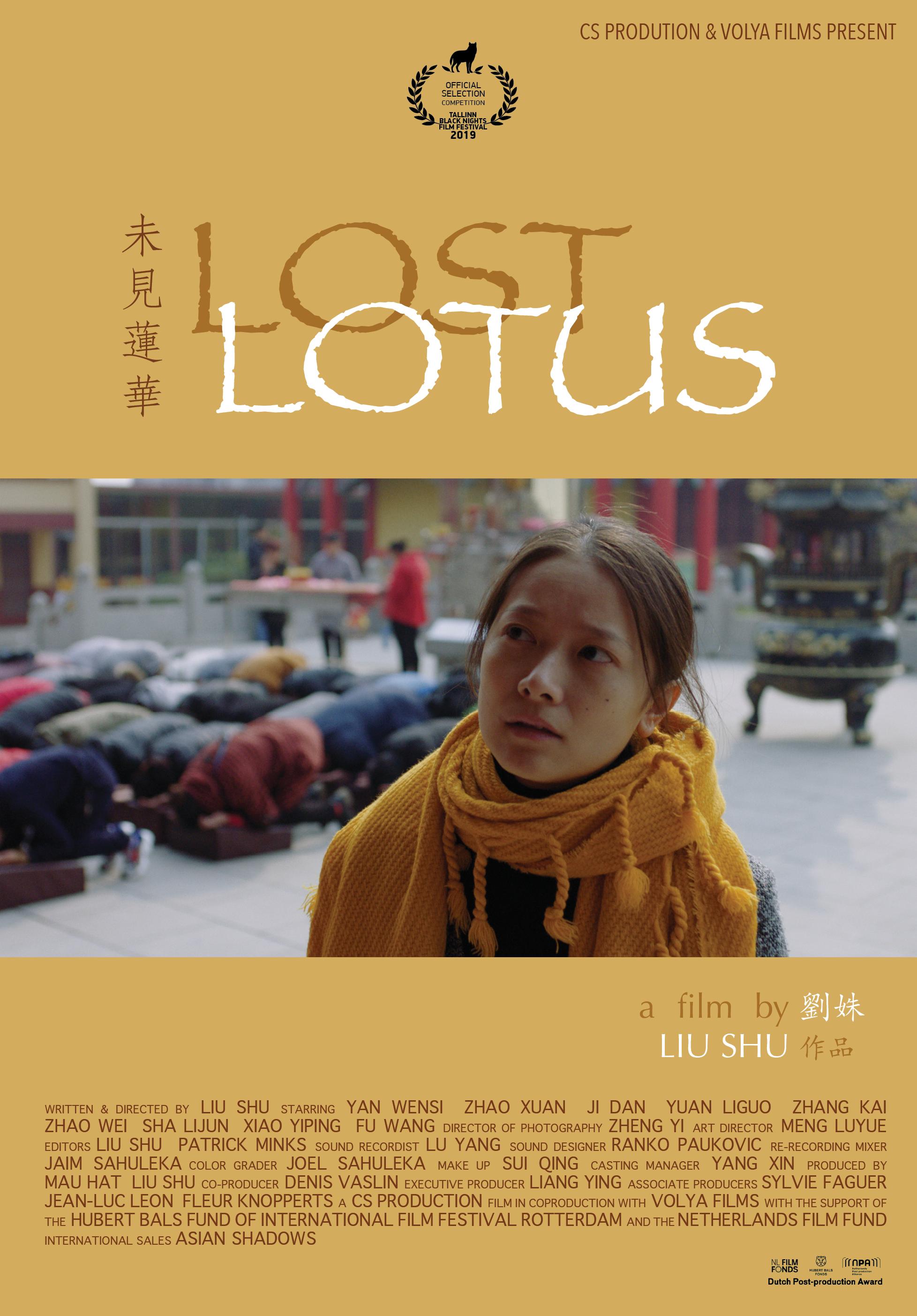

A grieving woman finds herself caught between the tenets of Buddhist thought and the contradictions of the modern China in Liu Shu’s emotionally complex drama, Lost Lotus (未见莲华, wèi jiàn lián huá). The paradoxes of Buddhism are, in a sense, a mirror for those of the contemporary society which has become mercilessly consumerist, obsessed with the material in direct rejection of the spiritual, yet even those who outwardly profess Buddhist values of compassion, goodness, and forgiveness are not perhaps free of the consumerist mindset in which everything has a price and for every transgression there is simply a fine to be paid in the next life rather than this.

An intellectual teacher, Wu Yu (Yan Wensi) describes herself as irritated by her mother’s (Zhao Wei) devotion to Buddhism, viewing it in a sense as slightly backward and superstitious. Nevertheless when her mother is suddenly killed in a late night hit and run, she finds herself agreeing to hold a traditional Buddhist funeral guided by her mother’s friends at the temple despite having been warned by the police that going ahead with the cremation will obviously make it much more difficult to find the killer. While immersing herself in Buddhist thought helps her reconnect with her mother and deal with her grief, she continues to search for the driver determined to get some kind of Earthly justice in addition to the karmic.

Increasingly worried and frustrated by Yu’s growing religious mania, her husband (Zhao Xuan) concentrates on finding those responsible in the hope of bringing closure so that they can try to move on with their lives as a couple. A kind and compassionate, modern man (he evidently does all the cooking), Yu’s husband does his best to support his wife in the depths of her grief but is himself conflicted particularly when he discovers that the man driving the car is a member of a rich and powerful elite who believes himself to be above the laws of men.

Yu’s newfound Buddhism begins to change her outlook, though she struggles to orient herself in a world which is so at odds with its twin contradictory philosophies. Running parallel to her own quest for justice, she finds herself drawn into the struggles of one of her pupils who wanted to quit school because he has to look after his father who was badly beaten by thugs working for developers angry that he had refused relocation. Yu is originally quite unsympathetic, she and her husband blaming the boy’s father for valuing money over his life, cynically believing he must have been angling for a bigger compensation pay out though of course it is probably not so simple. While Yu and her husband are a two-income, professional household, the boy’s family are living in poverty having been evicted from their home, the father bedridden because of his injuries and therefore unable to work. Yu’s quest for justice strains her relationship with her husband and may later have economic consequences as his career prospects are used as a tool to convince them to back off, but her need for retribution affects only herself. The boy’s mother, however, feels terribly guilty knowing her obsessive quest to have the thugs held accountable is endangering her son’s future, but knowing also that she cannot simply give up and let them win.

This is exactly the dilemma that preoccupies Yu as she weighs up how much of her anger is personal and how much societal. The driver, Chen (Xiao Yiping), offers them sizeable compensation which her husband is minded to accept, not for its monetary value but because taking the money means it’s over. But Yu wants “justice”, she resents the idea that there was a price on her mother’s life or that the culprit can simply pay a fine to assuage his guilt. Even justice, it seems, has been commodified. Yet Chen is also a Buddhist, subverting his beliefs to absolve himself in emphasising that all is fated and Yu’s mother’s death is a result of her karma from a previous life. His sin now pay later philosophy grates with Yu, undermining her new found faith in the Buddhist principles of compassion and goodness as the supposed devotee directly refuses to apologise for his role in the death of her mother.

As her husband asks her, however, what sort of justice is she looking for? Does she want an apology, a jail sentence, to kill him with her own hands? Yu doesn’t know, lost in a fog of grief and spiritual confusion attempting to parse the contradictions of her mother’s faith and a society that has become selfish and consumerist, founded on elitist inequality which allows the rich and powerful to escape the constraints of conventional morality let alone the laws of men. In the end the only justice she can find is a retributive act of violence that perhaps forces Chen to feel something at least of her pain, paving the way for a kind of catharsis though not perhaps healing. An embittered portrait of the modern China, Lost Lotus suggests there can be no justice in an unjust society and only an eternal purgatory for those who cannot abandon their desire to find it.

Lost Lotus streamed as part of this year’s San Diego Asian Film Festival.