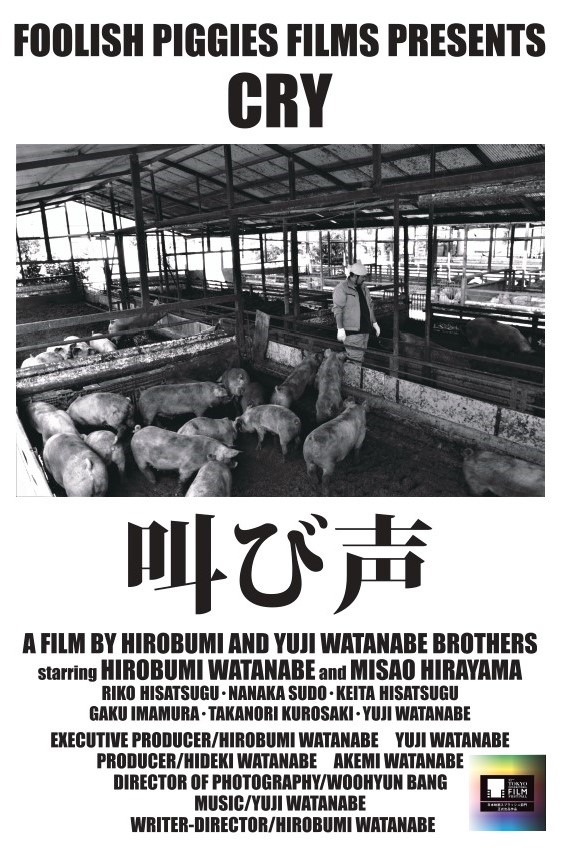

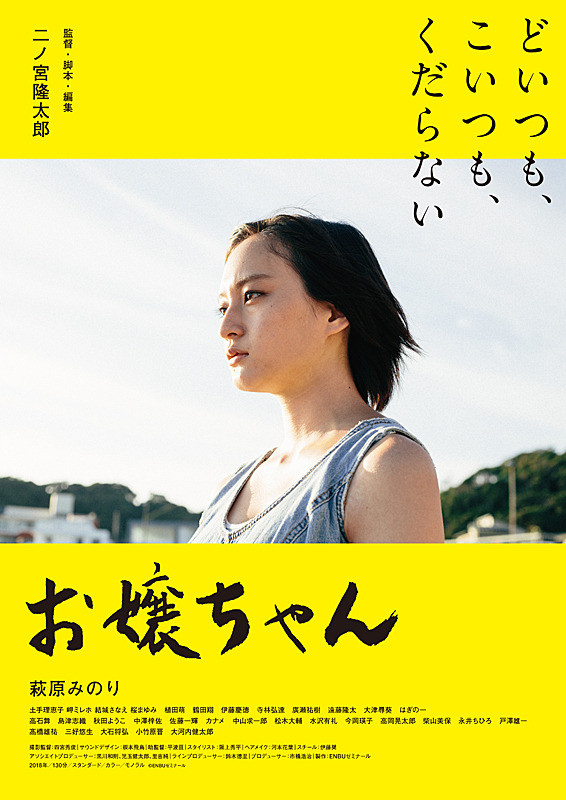

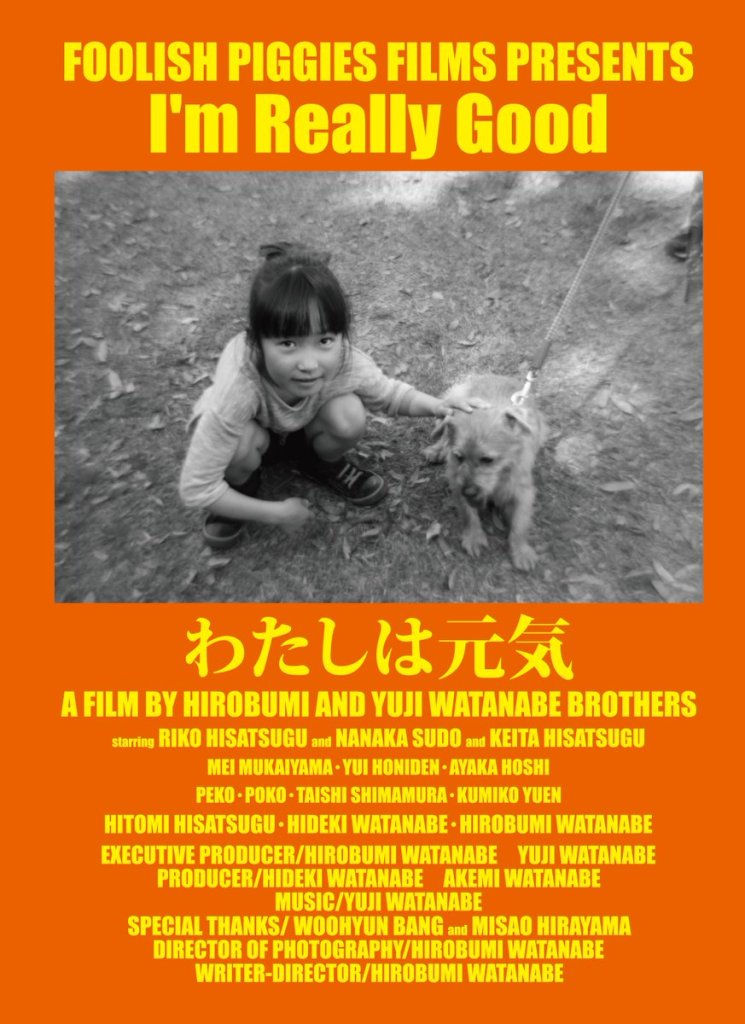

Hirobumi Watanabe has made a name for himself as a purveyor of deadpan wit, often shooting in a stark black and white and casting himself as a sometimes irate monologuer inhabiting a world of silence. With I’m Really Good (わたしは元気, Watashi wa Genki), however, he for the most part stays behind the camera which he operates for himself for the first time in the absence of regular cinematographer Bang Woo-hyun, and subverts the conceits of Poolsideman to show us the innocent world of childhood, following an energetic little girl through one ordinary, though as it turns out, packed with small incident day.

After opening with a colour sequence in which Riko (Riko Hisatsugu), a very energetic young girl, shoots an encouraging iPhone video, Watanabe returns to a more familiar black and white to find her playing with her best friend Nanaka (Nanaka Sudo), and then waking up to the sound of bird song ready for a brand new day. Like the hero of Poolsideman, she is constantly exposed to the radio news though, we can assume, she is not the one who put it on or actively listening to it. The central irony is that, where Poolsideman’s hero found himself driven in dangerous directions by reports of death, violence, and war, Riko is largely indifferent to the current pensions crisis which seems to be dominating the news. As a child, pensions are not something she is particularly worried about, though in a very real sense this will one day affect her especially in its implications for Japan’s rapidly ageing society as the discussion moves on to potential tax reform and ideas to combat a stagnating economy. In any case, Riko carries on playing happily with her friends, the news washing over her as perhaps it should.

Meanwhile, her days are filled with ordinary things like walking to school with her brother and Nanaka, chatting about what’s for lunch and what they had for dinner, playing shiritori, and enjoying the pleasant rural landscape. In the evening they make the exact same journey in reverse, returning to their homes where they do their homework and wait patiently for their parents to return from their jobs to make dinner. On this particular day, two unusual events occur the first being she’s ended up with Nanaka’s homework book by mistake and needs to return it. The second is a visit from a strange man with the bizarre name of Kamekichi Jinguji (Hirobumi Watanabe) who claims to be from a company selling textbooks that will send even the dimmest of students to the top of the class.

Luckily Riko is not duped by Kamekichi whose rather bizarre scam is undermined when she tells him her dad’s a policeman which sends him into a bit of a panic, but his presence does perhaps hark back to the pensions crisis as Riko finds herself targeted by a problem which is usually associated with the elderly in being doorstepped by a fraudulent salesman taking advantage of the fact she is currently without responsible adults with both parents out working. He tries the same thing with Nanaka who is almost taken in, but catches her just after Riko has arrived to give the book back, pausing only to remind the girls that they are the future and it’s their job to build a better Japan. Particularly ironic advice from a guy conning children out of their pocket money in exchange for phoney textbooks, not to mention somewhat unfair in projecting the responsibility for fixing a series of social problems like the pensions crisis into the future when it’s people like him who should be fixing them now to make the better world possible while little girls like Riko and Nanaka play happily enjoying a carefree childhood.

To that matter, Riko’s childhood seems to be pretty carefree. She hangs out with Nanaka, plays football, enjoys the pleasant country environment and is surrounded by loving family even if sad that her policeman dad often works late and can’t join them for dinner while her older brother is forever playing video games at the table. The politicians on the news debate what standard of life is appropriate, trying to get out of their responsibilities by splitting hairs about the “model family”, but Riko carries on enjoying her ordinary days oblivious to the troubles of the world around her. “I’m really good!” she affirms in her introductory video after politely enquiring after the viewers’ health, and it’s as good a mission statement as you’re likely to find.

I’m Really Good is available to stream worldwide until July 4 as part of this year’s Udine Far East Film Festival.

Festival trailer (English captions)