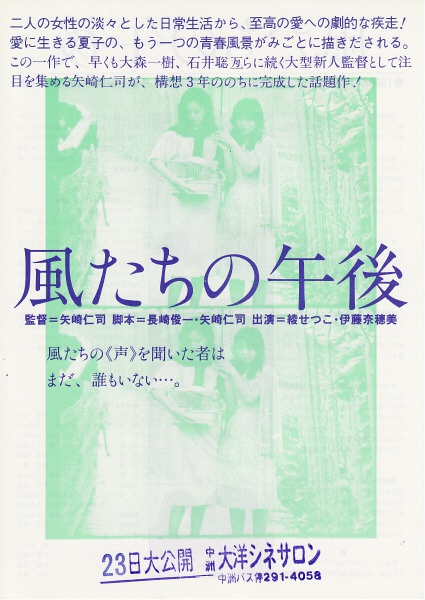

Even in the Japan of 1980, many kinds of love are impossible. Afternoon Breezes (風たちの午後, Kazetachi no gogo), the indie debut from Hitoshi Yazaki follows just one of them as a repressed gay nursery nurse falls hopelessly in love with her straight roommate. Based on a salacious newspaper report of the time, Afternoon Breezes is a textbook examination of obsessive unrequited love as its heroine is drawn ever deeper into a spiral of inescapable despair and incurable loneliness.

Nursery nurse Natsuko (Setsuko Aya) is in love with her hairdresser roommate Mitsu (Naomi Ito), who seems to be completely oblivious of her friend’s feelings. Mitsu has a boyfriend, Hideo (Hiroshi Sugita), and the relationship is becoming serious enough to have Natsuko worried. Hideo, unlike Mitsu, is pretty sure Natsuko is a lesbian and in love with his girlfriend but finds the situation amusing more than anything else. Beginning to go out of her mind with frustration, Natsuko tries just about everything she can to break Mitsu and Hideo up including introducing him to another pretty girl from the nursery, Etsuko (Mari Atake). Hideo is not exactly a great guy and shows interest in Etsuko though does not seem as intent on leaving Mitsu as Natsuko had hoped. Desperate times call for desperate measures and so Natsuko steels herself against her revulsion of men and seduces Hideo on the condition that he end things with her beloved Mitsu. He does, but the plan goes awry when Natsuko realises she is pregnant with Hideo’s child.

Less about lesbianism and more about love which can never be returned slowly eroding a mind, Afternoon Breezes perfectly captures the hopeless fate of its heroine as she idly dreams a future for herself which she knows she will never have. Natsuko buys expensive gifts for her roommate, returns home with flowers and courts her in all of the various ways a shy lover reveals themselves but if Mitsu ever recognises these overtures for what they are she never acknowledges them. Her boyfriend, Hideo, seems more worldly wise and makes a point of cracking jokes about Natsuko, asking Mitsu directly if her friend has a crush on her but Mitsu always laughs the questioning off. Mitsu may know on some level that Natsuko is in love with her, she seems to be aware of her distaste for men even if she tries to take her out to pick one up, but if she does it’s a truth she does not want to own and when it is finally impossible to ignore she will have nothing to do with it.

Despite Mitsu’s ongoing refusal to confront the situation, Natsuko basks in idealised visions of domesticity as she and Mitsu enjoy a romantic walk in the rain only to have their reverie interrupted by a passing pram containing a newborn baby. What Natsuko wants is a conventional family life with Mitsu, including children. After their walk, the pair adopt a pet mouse which Natsuko comes to think of as their “baby” but like a grim harbinger of her unrealisable dream, the mouse dies leading Mitsu to bundle it into a envelope and leave it on a rubbish heap along with Natsuko’s heart and dreams for the future.

When her colleagues at the nursery get stuck into the girl talk and ask Natsuko about boyfriends, her response is that she would not “degrade” herself yet that is exactly what she finally resorts to in an increasingly desperate effort to get close to Mitsu. After her attempts to get him to fall for another girl fail, Natsuko’s last sacrificial offering is her own body, surrendered on the altar of love as she pleads with the heartless Hideo to leave Mitsu for good. Though her bodily submission is painful to watch in her obvious discomfort her mental degradation has been steadily progressing as Hideo deliberately places himself between the two women, even going so far as to disrupt a seaside holiday planned for two by inviting himself along.

Yazaki perfectly captures Natsuko’s ever fracturing mental state through the inescapable presence of the dripping tap in the girls’ apartment which becomes a dangerous ticking in Natsuko’s time bomb mind. Occasionally gelling with clocks and doors and other oppressive noises, the internal banging inside Natsuko’s head only intensifies as she’s forced to endure the literal banging of Mitsu and Hideo’s lovemaking during her romantic getaway. Just as an earlier scene found Natsuko sitting on the swing outside embracing the flowers she’d brought for Mitsu only to find Hideo already there, Natsuko’s fate is to be perpetually left out in the cold, eventually resorting to rifling through her true love’s rubbish and biting into a half eaten apple in a desperate attempt at contact.

Natsuko’s love is an impossible one, not only because Mitsu is unable to return it, but because it is essentially unembraceable. In a society where her love is a taboo, Natsuko is not able to voice her desires clearly or live in an ordinary, straightforward way but is forced to act with clandestine subtlety. After Hideo unwittingly deflowers her and laughs about it, stating that she “must really be gay” Natsuko lunges at him with a knife, suddenly overburdened with one degradation too many. Though the prospect of the baby may raise the possibility of a happy family, albeit an unconventional one, the signs point more towards funerals than christenings, so devoid of hope does Natsuko’s world seem to be. Shot in a crisp 16mm black and white, Afternoon Breezes owes an obvious debt to the art films of twenty years before with its long takes, static camera giving way to handheld, and flower-filled conclusion, but adds an additional layer of youthful anxiety as its heroines find themselves moving into a more prosperous, socially liberal age only to discover some dreams are still off limits.

These days we think of Sion Sono as the recently prolific, slightly mellowed former enfant terrible of the Japanese indie cinema scene. Hitting the big time with his four hour tale of religion and rebellion Love Exposure before more recently making a case for ruined youth in the aftermath of a disaster in Himizu or lamenting the state of his nation in Land of Hope what we expect of him is an energetic, sometimes ironic assault on contemporary culture. However, his beginnings were equally as varied as his modern output and his first feature length film, Bicycle Sighs (自転車吐息, Jidensha Toiki), owes much more to new wave malaise than to post-punk rage.

These days we think of Sion Sono as the recently prolific, slightly mellowed former enfant terrible of the Japanese indie cinema scene. Hitting the big time with his four hour tale of religion and rebellion Love Exposure before more recently making a case for ruined youth in the aftermath of a disaster in Himizu or lamenting the state of his nation in Land of Hope what we expect of him is an energetic, sometimes ironic assault on contemporary culture. However, his beginnings were equally as varied as his modern output and his first feature length film, Bicycle Sighs (自転車吐息, Jidensha Toiki), owes much more to new wave malaise than to post-punk rage.