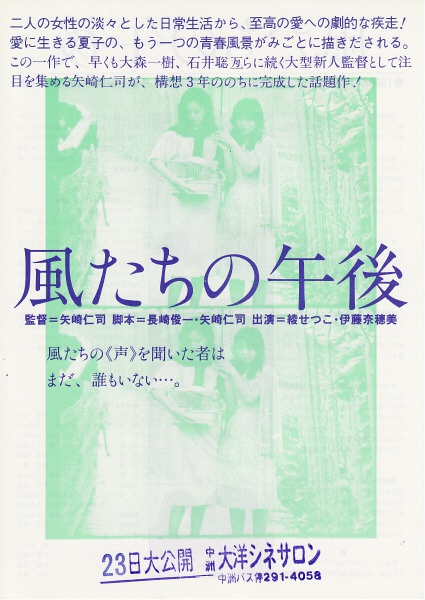

Even in the Japan of 1980, many kinds of love are impossible. Afternoon Breezes (風たちの午後, Kazetachi no gogo), the indie debut from Hitoshi Yazaki follows just one of them as a repressed gay nursery nurse falls hopelessly in love with her straight roommate. Based on a salacious newspaper report of the time, Afternoon Breezes is a textbook examination of obsessive unrequited love as its heroine is drawn ever deeper into a spiral of inescapable despair and incurable loneliness.

Nursery nurse Natsuko (Setsuko Aya) is in love with her hairdresser roommate Mitsu (Naomi Ito), who seems to be completely oblivious of her friend’s feelings. Mitsu has a boyfriend, Hideo (Hiroshi Sugita), and the relationship is becoming serious enough to have Natsuko worried. Hideo, unlike Mitsu, is pretty sure Natsuko is a lesbian and in love with his girlfriend but finds the situation amusing more than anything else. Beginning to go out of her mind with frustration, Natsuko tries just about everything she can to break Mitsu and Hideo up including introducing him to another pretty girl from the nursery, Etsuko (Mari Atake). Hideo is not exactly a great guy and shows interest in Etsuko though does not seem as intent on leaving Mitsu as Natsuko had hoped. Desperate times call for desperate measures and so Natsuko steels herself against her revulsion of men and seduces Hideo on the condition that he end things with her beloved Mitsu. He does, but the plan goes awry when Natsuko realises she is pregnant with Hideo’s child.

Less about lesbianism and more about love which can never be returned slowly eroding a mind, Afternoon Breezes perfectly captures the hopeless fate of its heroine as she idly dreams a future for herself which she knows she will never have. Natsuko buys expensive gifts for her roommate, returns home with flowers and courts her in all of the various ways a shy lover reveals themselves but if Mitsu ever recognises these overtures for what they are she never acknowledges them. Her boyfriend, Hideo, seems more worldly wise and makes a point of cracking jokes about Natsuko, asking Mitsu directly if her friend has a crush on her but Mitsu always laughs the questioning off. Mitsu may know on some level that Natsuko is in love with her, she seems to be aware of her distaste for men even if she tries to take her out to pick one up, but if she does it’s a truth she does not want to own and when it is finally impossible to ignore she will have nothing to do with it.

Despite Mitsu’s ongoing refusal to confront the situation, Natsuko basks in idealised visions of domesticity as she and Mitsu enjoy a romantic walk in the rain only to have their reverie interrupted by a passing pram containing a newborn baby. What Natsuko wants is a conventional family life with Mitsu, including children. After their walk, the pair adopt a pet mouse which Natsuko comes to think of as their “baby” but like a grim harbinger of her unrealisable dream, the mouse dies leading Mitsu to bundle it into a envelope and leave it on a rubbish heap along with Natsuko’s heart and dreams for the future.

When her colleagues at the nursery get stuck into the girl talk and ask Natsuko about boyfriends, her response is that she would not “degrade” herself yet that is exactly what she finally resorts to in an increasingly desperate effort to get close to Mitsu. After her attempts to get him to fall for another girl fail, Natsuko’s last sacrificial offering is her own body, surrendered on the altar of love as she pleads with the heartless Hideo to leave Mitsu for good. Though her bodily submission is painful to watch in her obvious discomfort her mental degradation has been steadily progressing as Hideo deliberately places himself between the two women, even going so far as to disrupt a seaside holiday planned for two by inviting himself along.

Yazaki perfectly captures Natsuko’s ever fracturing mental state through the inescapable presence of the dripping tap in the girls’ apartment which becomes a dangerous ticking in Natsuko’s time bomb mind. Occasionally gelling with clocks and doors and other oppressive noises, the internal banging inside Natsuko’s head only intensifies as she’s forced to endure the literal banging of Mitsu and Hideo’s lovemaking during her romantic getaway. Just as an earlier scene found Natsuko sitting on the swing outside embracing the flowers she’d brought for Mitsu only to find Hideo already there, Natsuko’s fate is to be perpetually left out in the cold, eventually resorting to rifling through her true love’s rubbish and biting into a half eaten apple in a desperate attempt at contact.

Natsuko’s love is an impossible one, not only because Mitsu is unable to return it, but because it is essentially unembraceable. In a society where her love is a taboo, Natsuko is not able to voice her desires clearly or live in an ordinary, straightforward way but is forced to act with clandestine subtlety. After Hideo unwittingly deflowers her and laughs about it, stating that she “must really be gay” Natsuko lunges at him with a knife, suddenly overburdened with one degradation too many. Though the prospect of the baby may raise the possibility of a happy family, albeit an unconventional one, the signs point more towards funerals than christenings, so devoid of hope does Natsuko’s world seem to be. Shot in a crisp 16mm black and white, Afternoon Breezes owes an obvious debt to the art films of twenty years before with its long takes, static camera giving way to handheld, and flower-filled conclusion, but adds an additional layer of youthful anxiety as its heroines find themselves moving into a more prosperous, socially liberal age only to discover some dreams are still off limits.

The well known Natsume Soseki novel, Botchan, tells the story of an arrogant, middle class Tokyoite who reluctantly accepts a teaching job at a rural school where he relentlessly mocks the locals’ funny accent and looks down on his oikish pupils all the while dreaming of his loyal family nanny. Hiroshi Shimizu’s Nobuko (信子) is almost an inverted picture of Soseki’s work as its titular heroine travels from the country to a posh girls’ boarding school bringing her country bumpkin accent and no nonsense attitude with her. Like Botchan, though for very different reasons, Nobuko also finds herself at odds with the school system but remains idealistic enough to recommend a positive change in the educational environment.

The well known Natsume Soseki novel, Botchan, tells the story of an arrogant, middle class Tokyoite who reluctantly accepts a teaching job at a rural school where he relentlessly mocks the locals’ funny accent and looks down on his oikish pupils all the while dreaming of his loyal family nanny. Hiroshi Shimizu’s Nobuko (信子) is almost an inverted picture of Soseki’s work as its titular heroine travels from the country to a posh girls’ boarding school bringing her country bumpkin accent and no nonsense attitude with her. Like Botchan, though for very different reasons, Nobuko also finds herself at odds with the school system but remains idealistic enough to recommend a positive change in the educational environment. Isn’t it sad that it’s always the kids that end up hurt when parents fight? Throughout Shimizu’s long career of child centric cinema, the one recurring motif is in the sheer pain of a child who suddenly finds the other kids won’t play with him anymore even though he doesn’t think he’s done anything wrong. Four Seasons of Children (子どもの四季, Kodomo no Shiki) is actually a kind of companion piece to

Isn’t it sad that it’s always the kids that end up hurt when parents fight? Throughout Shimizu’s long career of child centric cinema, the one recurring motif is in the sheer pain of a child who suddenly finds the other kids won’t play with him anymore even though he doesn’t think he’s done anything wrong. Four Seasons of Children (子どもの四季, Kodomo no Shiki) is actually a kind of companion piece to  It would be a mistake to say that Hiroshi Shimizu made “children’s films” in that his work is not particularly intended for younger audiences though it often takes their point of view. This is certainly true of one of his most well known pieces, Children in the Wind (風の中の子供, Kaze no Naka no Kodomo), which is told entirely from the perspective of the two young boys who suddenly find themselves thrown into an entirely different world when their father is framed for embezzlement and arrested. Encompassing Shimizu’s constant themes of injustice, compassion and resilience, Children in the Wind is one of his kindest films, if perhaps one of his lightest.

It would be a mistake to say that Hiroshi Shimizu made “children’s films” in that his work is not particularly intended for younger audiences though it often takes their point of view. This is certainly true of one of his most well known pieces, Children in the Wind (風の中の子供, Kaze no Naka no Kodomo), which is told entirely from the perspective of the two young boys who suddenly find themselves thrown into an entirely different world when their father is framed for embezzlement and arrested. Encompassing Shimizu’s constant themes of injustice, compassion and resilience, Children in the Wind is one of his kindest films, if perhaps one of his lightest. It’s tough being young. The Boss’ Son At College (大学の若旦那, Daigaku no Wakadanna) is the first, and only surviving, film in a series which followed the adventures of the well to do son of a soy sauce manufacturer set in the contemporary era. Somewhat autobiographical, Shimizu’s film centres around the titular boss’ son as he struggles with conflicting influences – those of his father and the traditional past and those of his forward looking, hedonistic youth.

It’s tough being young. The Boss’ Son At College (大学の若旦那, Daigaku no Wakadanna) is the first, and only surviving, film in a series which followed the adventures of the well to do son of a soy sauce manufacturer set in the contemporary era. Somewhat autobiographical, Shimizu’s film centres around the titular boss’ son as he struggles with conflicting influences – those of his father and the traditional past and those of his forward looking, hedonistic youth. Like many other areas of the world in the first half of the 20th century, Japan also found itself at a dividing line of political thought with militarism on the rise from the late 1920s. Despite the onward march of right-wing ideology, the left was not necessarily silent. Ironically, the then voiceless cinema was able to speak for those who were its greatest consumers as an accidental genre was born detailing the everyday hardships faced by those at the bottom end of the ladder. These “proletarian films” or “tendency films” (keiko eiga) were increasingly suppressed as time went on yet, in contrast to the more politically overt cinema of the independent Proletarian Film League of Japan, continued to be produced by mainstream studios. Long thought lost, Shigeyoshi Suzuki’s What Made Her Do It? (何が彼女をそうさせたか, Nani ga Kanojo wo Sousaseta ka) was a major hit on its original release with some press reports even claiming the film provoked riots when audiences were passionately moved by the heroine’s tragic descent into madness and arson after suffering countless cruelties in an unfeeling world.

Like many other areas of the world in the first half of the 20th century, Japan also found itself at a dividing line of political thought with militarism on the rise from the late 1920s. Despite the onward march of right-wing ideology, the left was not necessarily silent. Ironically, the then voiceless cinema was able to speak for those who were its greatest consumers as an accidental genre was born detailing the everyday hardships faced by those at the bottom end of the ladder. These “proletarian films” or “tendency films” (keiko eiga) were increasingly suppressed as time went on yet, in contrast to the more politically overt cinema of the independent Proletarian Film League of Japan, continued to be produced by mainstream studios. Long thought lost, Shigeyoshi Suzuki’s What Made Her Do It? (何が彼女をそうさせたか, Nani ga Kanojo wo Sousaseta ka) was a major hit on its original release with some press reports even claiming the film provoked riots when audiences were passionately moved by the heroine’s tragic descent into madness and arson after suffering countless cruelties in an unfeeling world.

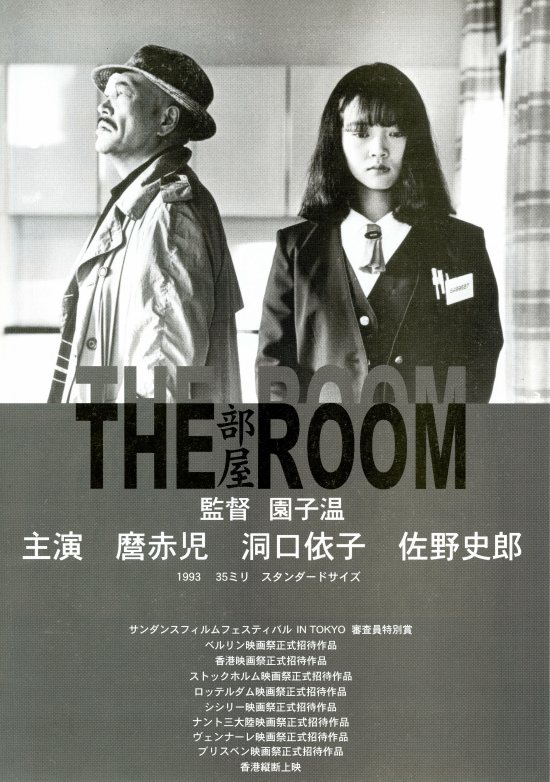

Though the later work of Sion Sono is often noted for its cinematic excess, his earlier career saw him embracing the art of minimalism. The Room (部屋, Heya) finds him in the realms of existentialist noir as a grumpy hitman whiles away his remaining time in the search for the perfect apartment guided only by a detached estate agent.

Though the later work of Sion Sono is often noted for its cinematic excess, his earlier career saw him embracing the art of minimalism. The Room (部屋, Heya) finds him in the realms of existentialist noir as a grumpy hitman whiles away his remaining time in the search for the perfect apartment guided only by a detached estate agent. Hibari Misora was one of the leading lights of the post-war entertainment world. Largely active as a chart topping ballad singer, she also made frequent forays into the movies notably starring with fellow musical stars Izumi Yukimura and Chiemi Eri in the

Hibari Misora was one of the leading lights of the post-war entertainment world. Largely active as a chart topping ballad singer, she also made frequent forays into the movies notably starring with fellow musical stars Izumi Yukimura and Chiemi Eri in the  Pop stars invading the cinematic realm either for reasons of commerce, vanity, or just simple ambition is hardly a new phenomenon and even continues today with the biggest singers of the era getting to play their own track over the closing credits of the latest tentpole feature. This is even more popular in Japan where idol culture dominates the entertainment world and boy bands boys are often top of the list for any going blockbuster (wisely or otherwise). Cycling back to 1955 when the phenomenon was at its heyday all over the world, So Young, So Bright (ジャンケン娘, Janken Musume) is the first of four so called “three girl” (Sannin Musume) musicals which united the three biggest female singers of the post-war era: Hibari Misora, Chiemi Eri, and Izumi Yukimura for a music infused comedy caper.

Pop stars invading the cinematic realm either for reasons of commerce, vanity, or just simple ambition is hardly a new phenomenon and even continues today with the biggest singers of the era getting to play their own track over the closing credits of the latest tentpole feature. This is even more popular in Japan where idol culture dominates the entertainment world and boy bands boys are often top of the list for any going blockbuster (wisely or otherwise). Cycling back to 1955 when the phenomenon was at its heyday all over the world, So Young, So Bright (ジャンケン娘, Janken Musume) is the first of four so called “three girl” (Sannin Musume) musicals which united the three biggest female singers of the post-war era: Hibari Misora, Chiemi Eri, and Izumi Yukimura for a music infused comedy caper. Hiroshi Shimizu takes another relaxing sojourn in 1938’s The Masseurs and a Woman (按摩と女, Anma to Onna), this time in a small mountain resort populated by runaways and bullish student hikers. Once again Shimizu follows an atypical narrative structure which begins with the two blind masseurs of the title and the elegant lady from Tokyo but quickly broadens out to investigate the transient hotel environment with even a little crime based intrigue added to the mix.

Hiroshi Shimizu takes another relaxing sojourn in 1938’s The Masseurs and a Woman (按摩と女, Anma to Onna), this time in a small mountain resort populated by runaways and bullish student hikers. Once again Shimizu follows an atypical narrative structure which begins with the two blind masseurs of the title and the elegant lady from Tokyo but quickly broadens out to investigate the transient hotel environment with even a little crime based intrigue added to the mix.