There has of late been an unfortunate trend of historical revisionism in recent Chinese cinema which has sought to look back at the Cultural Revolution with a kind of fond remembrance for a more “innocent” time. Mostly coming from directors in their 50s and 60s who were themselves young during the last years of Maoism, films such as Feng Xiaogang’s Youth have attempted to draw a sharp contrast with the collectivist past and consumerist present as if to lament the passing of a kinder era, but have also largely located themselves within the cosseted group of youngsters working for the regime and therefore shielded from the intense cruelty of the age.

There has of late been an unfortunate trend of historical revisionism in recent Chinese cinema which has sought to look back at the Cultural Revolution with a kind of fond remembrance for a more “innocent” time. Mostly coming from directors in their 50s and 60s who were themselves young during the last years of Maoism, films such as Feng Xiaogang’s Youth have attempted to draw a sharp contrast with the collectivist past and consumerist present as if to lament the passing of a kinder era, but have also largely located themselves within the cosseted group of youngsters working for the regime and therefore shielded from the intense cruelty of the age.

Songs of the Youth 1969, the debut (and to this date only) narrative feature film from director Ye Jing, is much the same in this regard in that it deliberately recreates his own longed for adolescence as young man fighting, he thought at the time, for a better China. Lamenting that the young people of today have no idealism, he describes the Cultural Revolution as a “rock ‘n’ roll movement” in which intellectual youth chased love and freedom through venerating Mao. Looking at footage of himself on screen, he urges the youngsters not to pity the kids in the square even though they were being “brainwashed” but to admire them because they were fighting passionately for something they believed in.

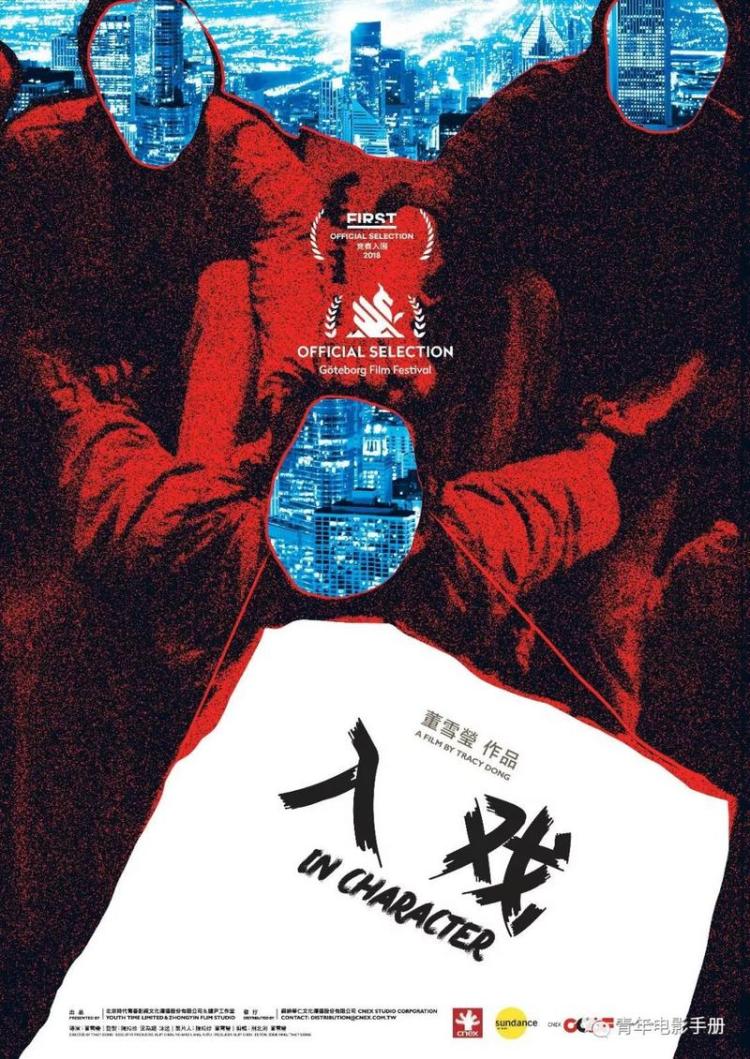

Dong Xueying, the director of In Character (入戏, Rùxì), came on board with the intention of exploring the living conditions of Chinese actors but quickly found herself sucked into an alternate reality in documenting the behind the scenes production of Songs of the Youth 1969 as Ye sends his cadre of youngsters off to an abandoned munitions factory in Sichuan for “the Cultural Revolution Experience”. During this time, they must prepare by living under contemporary conditions – wearing Red Army uniforms, surrendering their phones and other modern communication devices, and learning the various revolutionary songs which operated as a key part of the movement.

Although the young men and women are merely actors born long after the Cultural Revolution had ended, the “experience” quickly turns into a kind of social experiment along the lines of Stanford Prison as the intense mob mentality of the era begins to take hold. An early visit from Ye finds them furiously role playing, greeting him as if they were ghosts of his past waiting more than 40 years for his return. Playfully singing bawdy and suggestive songs, they embrace the sense of fun loving youth the director seems to be looking for but a fatal mistake by one young actor abruptly turns the tables, recalling the fear and danger that many must surely have felt in an era of intense suspicion puritanical scrutiny.

Many had openly laughed during rehearsals as they spouted the outdated Maoist quotations and learned the choreography for revolutionary ballet, but the fervour eventually takes hold and it’s not long before they begin turning on each other. First it’s a minor complaint blown out of all proportion about inattention and fiddling with fingernails instead of concentrating on collective concerns, and then an outright attack on one of their number who has made an obvious if understandable mistake – he asked for a few days off on hearing a relative was dangerously ill, and not only that, he misspelled Chairman Mao’s name in his apology letter. Jiang Siyuan’s request seriously upset Ye who is now convinced that the modern youth is selfish and irresponsible and that the youngsters still haven’t absorbed the spirit of the Cultural Revolution. Upset that Jiang may have ruined all their hard work, the actors subject him to a Struggle Session in which he must self criticise while they each berate him for damaging the integrity of their common project.

Ironically enough, the “film” has taken the place of the revolutionary ideal, while Ye has become a kind of Mao figure as a faraway authority whom they must worship and placate to make their dream come true. Despite their modern upbringings, the actors quickly succumb to the worst tendencies of the age as they consent to oppress each other, going along with the austerity of the ideology which instructs them to rid themselves of their “selfish” instincts in order to serve the collective while simultaneously emphasising their individual will to ensure their place in the film which necessarily means that Jiang must surrender his human feeling and accept he may never see his grandfather again.

Ye promises them the time of their lives in an experience he hopes will be life changing in the same way, presumably, he feels his own youthful brush with the revolution to have been, but their memories of the munitions factory are likely to be less positive as they ruminate on the immediacy with which they were able to betray each other in service of an empty ideal. Dong’s camera captures not only the misguided romanticisation of the Cultural Revolution by those like Ye disillusioned with the path of modern China, but its frightening legacy in the ease with which such inhumanity takes hold.

In Character was screened as part of the 2019 Chinese Visual Festival.

Original trailer (English subtitles)