As the heroine of Kota Yoshida’s Snowdrop (スノードロップ) says close to the end of the film, you can become used to living in miserable circumstances and bear it because it is your normal but being suddenly confronted by them does nothing other than compound your misery. At least that’s how it seemed to her while attempting to register for social security payments after her father suffers a workplace accident and needs surgery they can’t afford in order to be well enough to be employed and earn money.

Then again, her family circumstances are a little unusual in that her father, Eiji, left when she was little only to return 25 years later and ask to be taken in again swearing he’d work hard. Nearly 20 years after that, Naoko (Aki Nishihara) has had to give up working to care for her mother who has advanced dementia and requires round the clock care leaving Eiji as the only breadwinner though he is also elderly and working only as a newspaper delivery man which already makes it very difficult for them to make ends meet. It’s Eiji’s boss who suggests they apply for government help so that Eiji can get treatment for the gout that’s affecting his legs and get well enough to work again, though it’s clear that the family feel a degree of shame about the idea of accepting assistance even though as social worker Munemura points out it’s something that’s available to everyone should they ever need it.

The problem is however that you have to prove that you’re struggling which can be a long and difficult process. Naoko later describes it as a kind of humiliation, that she was forced to parade her penury and by doing so was confronted by the misery of her circumstances. Munemura describes her as a very earnest woman and is impressed by the way she meticulously fills in all the correct forms while the house, when they come to inspect it, is tidy and well kept (something which might actually go against you in other countries) even if they’re eying up her car and wondering if she really needs it. Munemura also sympathises with her on a personal level, realising from the forms that Eiji must have been absent from the family for an extended period and that they suffered because of it while it must also have been hard for Naoko caring for her severely ill mother alone for over 10 years.

Naoko herself has a largely beaten down, defeated aura in which she’s given up on the idea of a future for herself. She later describes caring for her mother as its own kind of escape in that she always found it difficult to get along with other people and never felt confident at work so being a carer became a kind of identity for her that she also feared losing if they were successful in their application and were able to secure nursing assistance for her mother. As well-meaning as Munemura is, she is not perhaps in the position of being able to see or deal with all sides of the issues someone like Naoko faces and is therefore shocked by the dark place her despair eventually takes her. Munemura faces a similar issue with a woman in her 70s whose claims that the cleaning job they insisted she take was simply too difficult for her at her age is treated with less than total sympathy by her slightly more cynical colleague.

A largely unexplored subplot in which it’s implied there was another sister who was given up because of the father’s abandonment and the family’s poverty hints at a deep-seated childhood trauma but also fissure within the family itself as Naoko explains her actions solely with the justification “we were a family” as if she too feared being left behind or abandoned even while her older sister has evidently been able have a family of her own though is also very sympathetic towards Naoko and in no way holds her responsible anything that happened. All she really wanted was an escape from her misery, which she may in a way get with the fresh shoots of a new life already visible to her if only she can embrace them. Shot with a detached naturalism, Yoshida’s drama is often bleak though does not lack for empathy and especially for those like Naoko who are largely left to deal with their misery all alone.

Snowdrop screened as part of this year’s Osaka Asian Film Festival.

Original trailer (English subtitles)

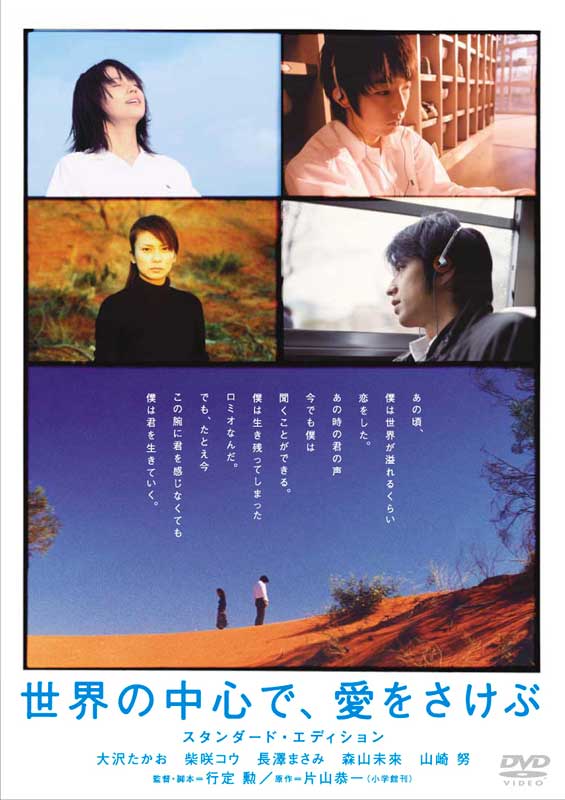

Just look at at that title for a second, would you? Crying Out Love, in the Center of the World, you’d be hard pressed to find a more poetically titled film even given Japan’s fairly abstract titling system. All the pain and rage and sorrow of youth seem to be penned up inside it waiting to burst forth. As you might expect, the film is part of the “Jun ai” or pure love genre and focusses on the doomed love story between an ordinary teenage boy and a dying girl. Their tragic romance may actually only occupy a few weeks, from early summer to late autumn, but its intensity casts a shadow across the rest of the boy’s life.

Just look at at that title for a second, would you? Crying Out Love, in the Center of the World, you’d be hard pressed to find a more poetically titled film even given Japan’s fairly abstract titling system. All the pain and rage and sorrow of youth seem to be penned up inside it waiting to burst forth. As you might expect, the film is part of the “Jun ai” or pure love genre and focusses on the doomed love story between an ordinary teenage boy and a dying girl. Their tragic romance may actually only occupy a few weeks, from early summer to late autumn, but its intensity casts a shadow across the rest of the boy’s life.