How should you deal with the traumatic past? In Chong Keat-Aun’s Snow in Midsummer (五月雪) it becomes clear that this past has not been dealt with and that its heroine has been living in a kind of limbo unable to move fully forward with her life in the constant search to discover what happened to her father and brother during the 513 Incident in 1969. The first act devotes itself to the slowly unfolding horror of the massacre which erupted shortly after a general election during which a number of smaller parties affiliated with the Chinese community had begun to gain ground from the Malay-dominated Alliance Party.

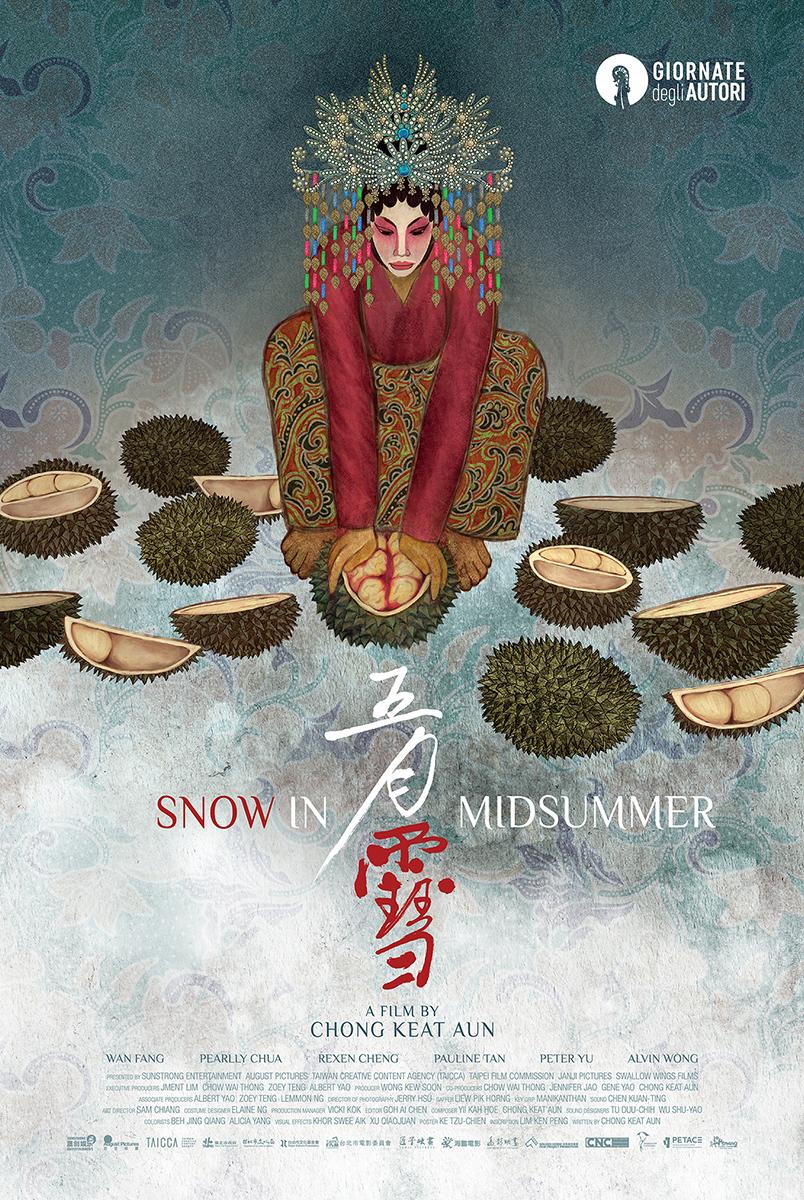

Bullied by her classmates as a Chinese student in a Malay school, Ah Eng spends the night of the massacre hiding in the backstage area of a Cantonese opera troupe as if in a literal act of taking refuge in fantasy. The film’s title alludes to the famous Cantonese opera Snow in Midsummer, actually “Snow in June” here retitled as “Snow in May”. The play’s theme is injustice as its heroine is condemned to die for a crime she didn’t commit, someone remarking that the gods must be outraged to provoke such an aberration of the natural order as snow in the height of summer. The ageing leader of the opera troupe ventures out during the incident in search her friends and relatives who had gone to the local cinema. Unable to open the door, she climbs onto the roof and sings a lament decrying the bloodshed and her own cruel fate as she watches the city burn beneath her.

A similar lament is sung 49 years later in a graveyard we’re told is set to be “redeveloped”. The opera troupe had performed here for the dead during the intervening years, but in an event echoing that of 1969 are challenged by authorities asking if they have permits. That was in the past, they’re told, this is now and their performance causes a disturbance to a mosque which has recently been built close to the site. In a touch of irony, the taxi driver who brings the middle-aged Ah Eng to the cemetery asks her if she’s going to the leprosy hospital remarking that the Chinese community usually refuse to go anywhere near it. Each of the headstones, many of which read simply “unknown Chinese”, is marked “courtesy of the Malaysian government”, but it’s clear that this site was chosen because of its remoteness for similar reasons to the leper colony because they did not really want to address what had happened in any meaningful way.

That Ah Eng returns 49 years later hints at spiritual echoes of cycles of rebirth, but Ah Eng has lives her whole life in limbo haunted by the impossibility of discovering the resting place of her father and brother. Her father had refused to take her to the cinema, leaving her and her mother to watch the opera alone in echoes of the patriarchal oppression she continues to face as a middle-aged woman whose husband reacts with violence and anger simply because he suspects she intends to return to Kuala Lumpur to mourn her loss. Her sister-in-law gives her a lift to the station, but insists on being called by her Chinese name revealing that’s divorced her Muslim husband and intends to move to Australia with her child. On her arrival in the city, Ah Eng passes by the former sit of the Majestic Theatre which is now a fancy hotel with the same name in a very changed city. Her former Malay school is now Chinese but has a stand outside it selling Islamic food where the Cantonese opera troupe discuss their visit to the cemetery.

“The past is dream,” the old woman sings to the grave echoing the surreality that runs through Chong Keat-Aun’s vision of the past as a man rides his elephant through the streets and lives the tale of a king forced to drink the Sultan’s foot water as a symbol of his subjugation, while others at the theatre are sold of a tale of a king with a quite literal bloodlust sustaining himself on the suffering of his subjects. A melancholy contemplation on lingering trauma, loss, and memory Chong Keat-Aun ends with a poignant image of comfort and catharsis but one is which is forever haunted by an intangible past and the wandering, unseen ghosts of buried injustice.

Snow in Midsummer screens as part of this year’s Taiwan Film Festival in Australia.

Trailer (Traditional Chinese / English subtitles)