What does “freedom” actually mean? Su I-Hsuan’s post-martial law drama Who’ll Stop the Rain? (青春並不溫柔) sees a younger generation struggle to shake off the authoritarian yoke meanwhile it seems clear that freedom has its limits and has not been granted equally to or by all. Set in 1994 it takes place against the longest student strike in the nation’s history and ultimately pits the forces of protest and complicity against each other in the constant struggle for individual freedom.

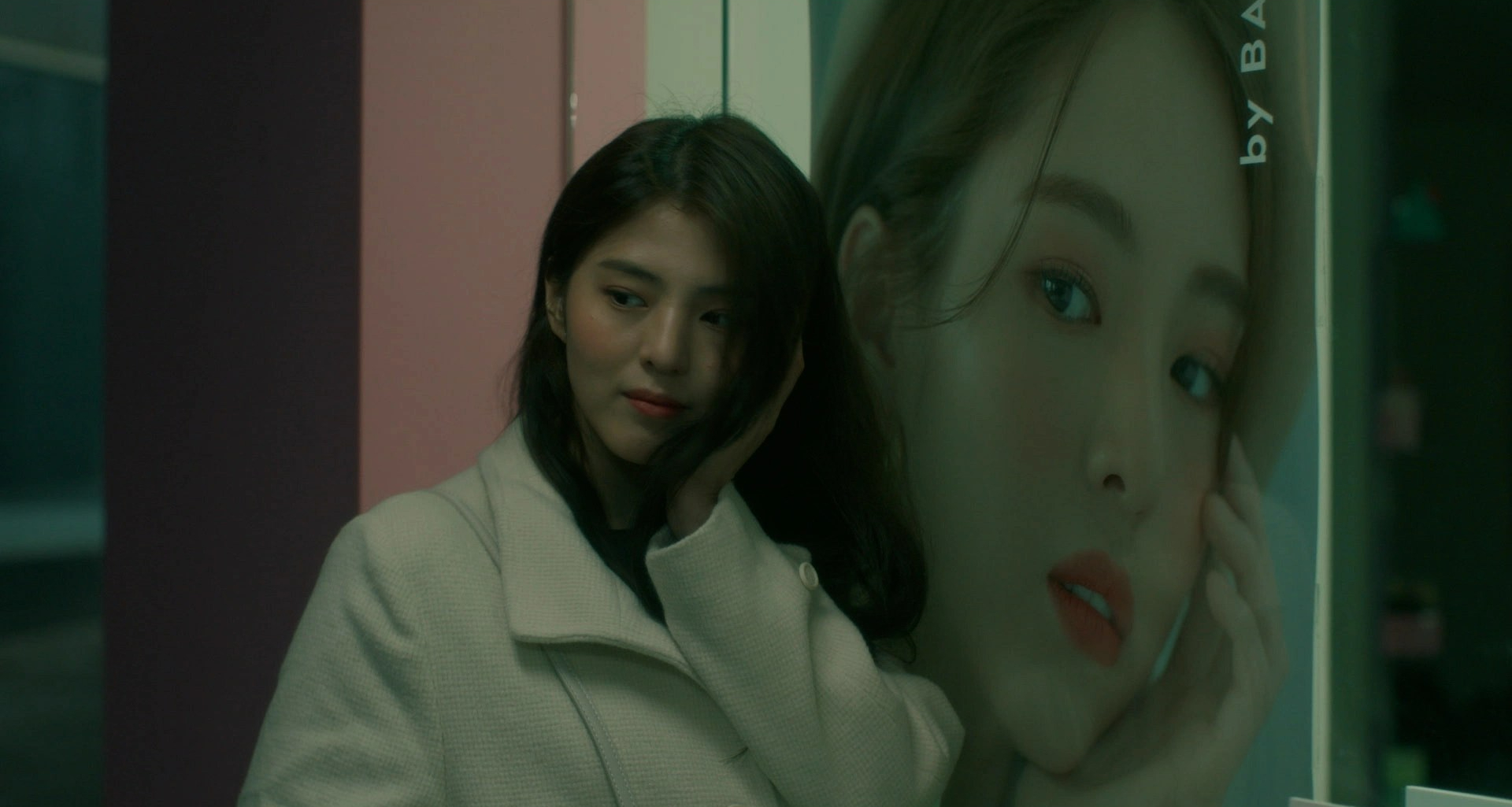

Free-spirited Chi-wei (Lily Lee) might be something of an outlier in this age, later expressing confusion to the comparatively repressed Ching that she doesn’t understand why they’re fighting for freedom when freedom was something they had always possessed. Yet at the university she finds herself constrained in what is supposed to be an artist’s school, denied creative freedom by stuffy professors who mark their students not by the quality of their work but their obedience and willingness to accept the lessons the professors see fit to give them. Chi-wei’s professor gives her telling off because he says her hair’s too messy, then humiliates her in front of the class by throwing her work on the floor and telling her to start again. Chi-wei, however, remains defiant and continues to work her own way regardless of what the teachers may say.

It’s after a chance encounter with Ching (Yeh Hsiao-Fei) that she’s drawn into the student movement which opposes the authoritarian rule of the professors and demands greater creative freedoms for the students and society at large as this generation who came of age after martial law considers the kind of future they envision for themselves. But like any student movement, there are innate tensions within the group with some suggesting that its leader, Kuang (Roy Chang), is merely trying to relive the White Lily movement and is in fact less committed to the cause than he seems as evidenced by his willingness to enter dialogue with the staff against the wishes of his girlfriend, Ching.

Unlike the others, Ching is a law student and not and artist. She’s also the daughter of a prominent, conservative and patriarchal politician and the group is somewhat ironically often dependent on her familial wealth. Her background perhaps makes it harder for her to emerge into a new, ostensibly freer age as bound by a set of ideas otherwise alien to Chi-wei who is at any rate absolutely herself and unafraid to be so. Ching tells her that she longs to be part of a group, which is presumably why she’s joined the artists in their protest even if others accuse her of simply rebelling against her privilege, which is something Chi-wei has little need for as she has already discovered the power of freeing her mind.

It’s these forces that generate the push and pull between the two women as Chi-wei is eventually awakened to her sexuality by Ching only to experience her pulling away in her deeply internalised shame. Even so, she takes an approach that largely avoids direct confrontation but allows her to stay by Ching’s side, patient yet confused in attempting to create a safe space that Ching can accept as her own. Both women are also constrained by forces of traditional patriarchy with even Kuang stating that perhaps women shouldn’t be too independent after all or else they wouldn’t need him in an ironic moment foreshadowing his total redundancy. Meanwhile, Chi-wei is aggressively pursued by a fellow student who won’t be deterred by her frequent rejections and general lack of interest in men while ironically trying to convince her she’s been “brainwashed” by the strikers and is really a good girl, like him willing to bend to the authoritarian yoke.

Perhaps it’s telling that it’s only once the strike is over and following a confrontation with her authoritarian father that Ching is able to overcome the barriers that prevent her from embracing her true desires and authentic self. In her opening voiceover, Chi-wei reflects that back then they still believed a tiny flame could burn down the forest implying at least that she was mistaken but even if a wider revolution ends if not exactly in failure than in compromise, disappointment, and rancour, it is true enough that the spark between these women was enough to burn through the forces that kept them apart to find a more individual kind of freedom that exists outside of oppressive superstructures even if as Ching says protest never ends.

Who’ll Stop the Rain screened as part of this year’s BFI Flare.

Trailer (English subtitles)