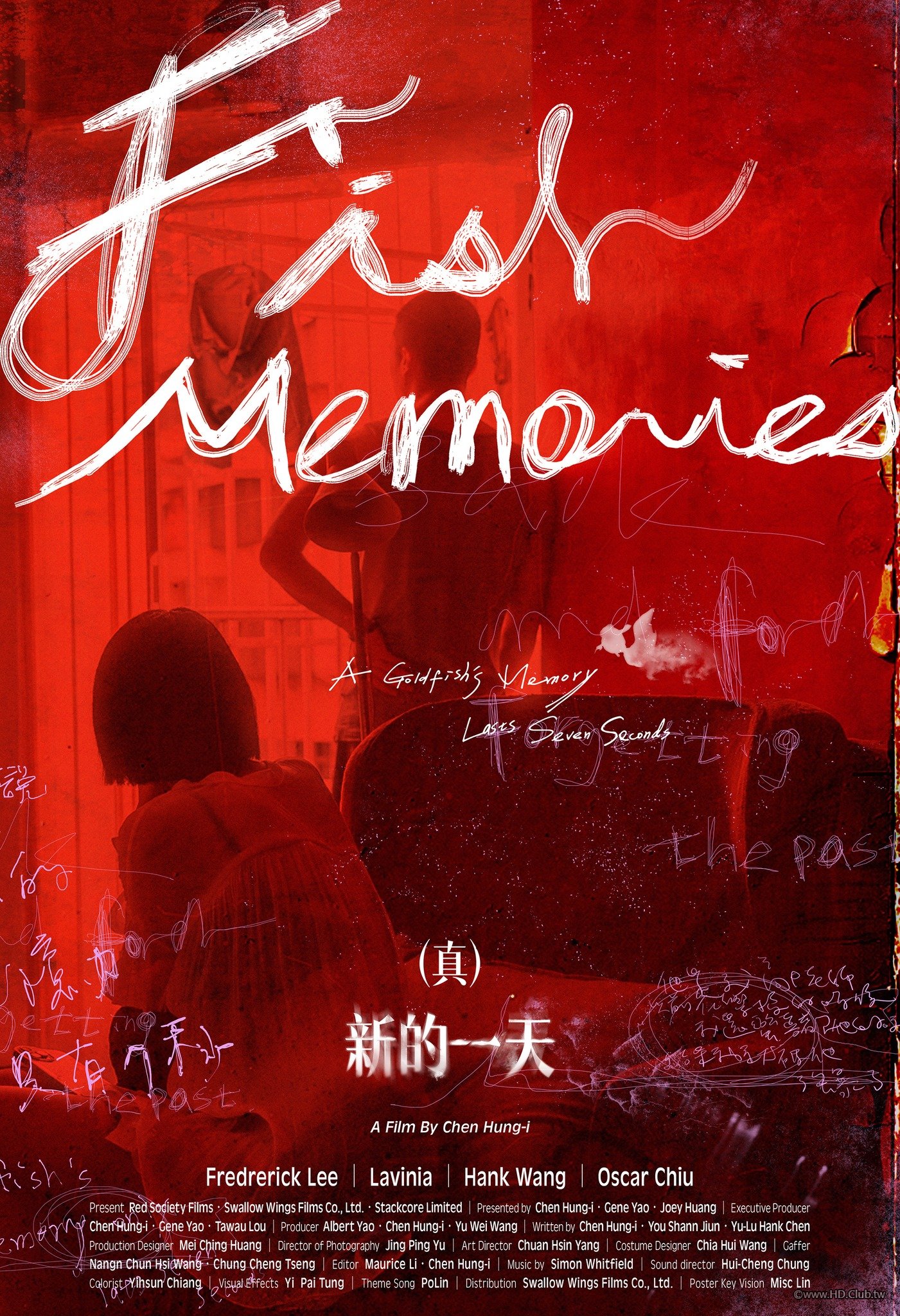

The sometime narrator at the heart of Fish Memories ((真)新的一天, (zhēn) Xīn de tiān) says that she wishes her memory were like that of a fish, no longer than seven seconds, and that she were able to be free of her traumatic past by forgetting it. But of course, she is unable to forget and like her boyfriend, Shang, and the middle-aged man with whom the pair eventually form a twisted relationship, a kind of orphan drifting in the wake of parental failure.

Businessman Zi Jie (Frederick Lee) also seems to drifting, seemingly dissatisfied with his financially comfortable but emotionally empty existence. He later says that his own parents only cared about about money and sent him away to Singapore when he was a teenager only for their business to then fail. He feels as if he’s done better than them, at least, but when asked how to avoid loneliness he answers only “earning money, spending money, earning money”. He has a girlfriend of around his own age, but bristles when she expresses a desire for greater intimacy and ends up pushing her away while beginning to bond with Shang (Hank Wang), a teenager he meets in a convenience store while picking up a parcel. He runs into the boy a few more times and ends up developing a friendship with him and also his same age girlfriend Zhen Zhen (Lavinia) who is still in high school and claims to have been sexually assaulted by one of her teachers who’s apparently done the same thing to several other girls with no apparent consequences.

Zi Jie’s relationship with the teens straddles an awkward divide, partly parental and partly friendly. He seems to partially regresses in their company, drinking incredibly expensive wine but also sitting around playing video games and agreeing to childish dares such as the one in which he ends up swapping places with Shang, waking up in his walkup apartment and dressing in his clothes. Shang’s living environment is not ideal, Zi Jie balks at the stairs while the place is cramped and filled with junk and Shang evidently rarely does no laundry but to Zi Jie it represents a kind of freedom. Of course, he can always return to his luxury apartment which still has power even during an outage which is an option not open to Shang who nevertheless seems to increase in confidence while wearing Zi Jie’s fancy tailored suit. Several times he approaches his rundown apartment block and looks to the sky as if echoing his sense of aspiration though that turns out not to be the reason he’s interested in Zi Jie.

When he first gave him a car ride, Shang blunts told Zi Jie he wouldn’t sleep with him because he liked girls, remarking that Zi Jie looked “a bit gay”, but a sexual relationship does eventually evolve between the trio even as they also form an unconventional family unit. When they sit down to breakfast together with the doors onto the courtyard open and the sun drifting in with idyllic view behind, Zhen Zhen remarks that it’s the kind of moment she’s been waiting for all her life despite the awkwardness of this quasi-incestous and definitely inappropriate relationship given that the teens are underage and Zi Jie is a wealthy middle-aged man keeping them in his apartment.

But it’s perhaps when the streams start to cross that things begin to go wrong, Zi Jie making a huge miscalcutation while in the teens’ world that provokes a tragic event biding each of them together though only in the darkest of ways. The three of them are each in their way trapped in a tank, no more free than the fish they place inside it and in the end able to find freedom, of one kind or another, by remembering and acknowledging the truth. Repressing his sexuality and chasing only empty financial success has evidently left Zi Jie a hollow, broken man seeking to reconnect with his younger self through his relationship with Shang which in its way also prevents him from acknowledging the vast gulf that exists between them in their differing circumstances but also unites them in a shared feeling of irresolvable loneliness and the legacy of parental abandonment in a sometimes indifferent society defined by economic success.

Fish Memories screens 8th September in Melbourne as part of this year’s Taiwan Film Festival in Australia.

Original trailer (Traditional Chinese / English subtitles)