Possession Street is a real street in Hong Kong, but its name doesn’t hint at the supernatural. Rather, it’s located on the former site of Possession Point where the British took possession of Hong Kong in 1841. Nevertheless, there is definitely some body snatching going on in Jack Lai’s claustrophobic zombie-esque horror set in the decidedly purgatorial space of a shopping centre on the brink of demolition.

Indeed, it’s the vendors themselves that are in someways zombies. Representatives of a generation that is tired of fighting and barely clinging on to what they’ve got, they run their moribund stores stubbornly refusing to move with the times almost as if they were haunting the place. A former stuntman, Sam (Philip Keung Hiu-Man) runs an unprofitable video shop that plays classic Hong Kong wuxia movies of the kind he used to be in. Sam’s wife left him taking their daughter Yan with her when the shop first ran into financial difficulty and Sam refused to do much about it other than swear it would figure itself out in the end.

Which is one way to say young Yan (Candy Wong Ka-Ching) escaped the mall, though she continues to idolise her father and has developed a love of film precisely because of what he taught her. She tells him that she’s dropping out of uni to become a filmmaker because she wants to keep Hong Kong cinema alive in what seems to be a meta comment on the state of the industry in which Hong Kong cinema itself has become a kind of zombie, like the vendors simply treading water while trapped in a constant state of decline in its conflicted necessity to please the Mainland censors.

In this way, the claustrophobic space of the post-war shopping centre stands in for Hong Kong itself. A place that’s lost its lustre and fallen behind the times, the mall has fallen into a state of disrepair. Many of the stores have already closed and there’s not much footfall. The mall has a serious rat problem, though really that’s about to be the least of its worries. Even so, it’s the rodents who are partially responsible for chewing on the power cables and requiring a trip to the super secret meter room where one of the vendors accidentally damages the seal keeping a not all that ancient evil from bubbling to the surface.

As the ghost later explains, like the vendors they are those who have been left behind by the new Hong Kong and cannot progress into its future. The mall was built on top of an air raid shelter which was sealed shut by an American bomb leaving all those inside to turn to depraved acts of survival such as cannibalism along with violent outrages like rape before dying horribly inside. Their resentment has awakened another ancient evil that wants to kill everyone in the world, beginning with everyone in the mall which is locked shut until the following morning. Clearly influenced by the the Last of Us with its fungal zombies who spread the curse by coughing up a visible miasma and are covered in pustular growths, the infected echo a particular face of evil such as the fat cat capitalist constant running down his daughter who is the only one who tries to help him. He remarks that he’s glad her brother never showed up, because now the family name will continue.

Meanwhile, Yan has been a part of this community since she was a child and fond attachments to many of the vendors including the Taoist priest whom she once-called Uncle Con-Man. Master Mak (Alan Yeung Wai-Leun) was entrusted with a mission by his former master who knew about the air raid shelter and was the guardian standing it over it, making the sure the evil didn’t leak out, but Mak has lost the faith and with the imminent demise of the shopping centre come to the conclusion that it’s time to call it quits. There is then something in the fact that this Taoist philosophy actually works and proves the only real way of overcoming the supernatural threat as if calling forth the spirit of Hong Kong. On the other hand, it’s really Yan who is trapped in this place and seeking escape in permission to move on but also to continue fighting for the Hong Kong that’s disappearing in keeping its cinema alive. When Sam tells her “ga you,” he echoes the words of the protestors while ironically telling her not to give up even though life rarely turns out the way you hoped. In effect, she liberates them all including herself from a self-imposed limbo of resigned stagnation while walking into the light of a new day determined to fight for the kind of future she wants for herself rather than what anyone else might have wanted for her.

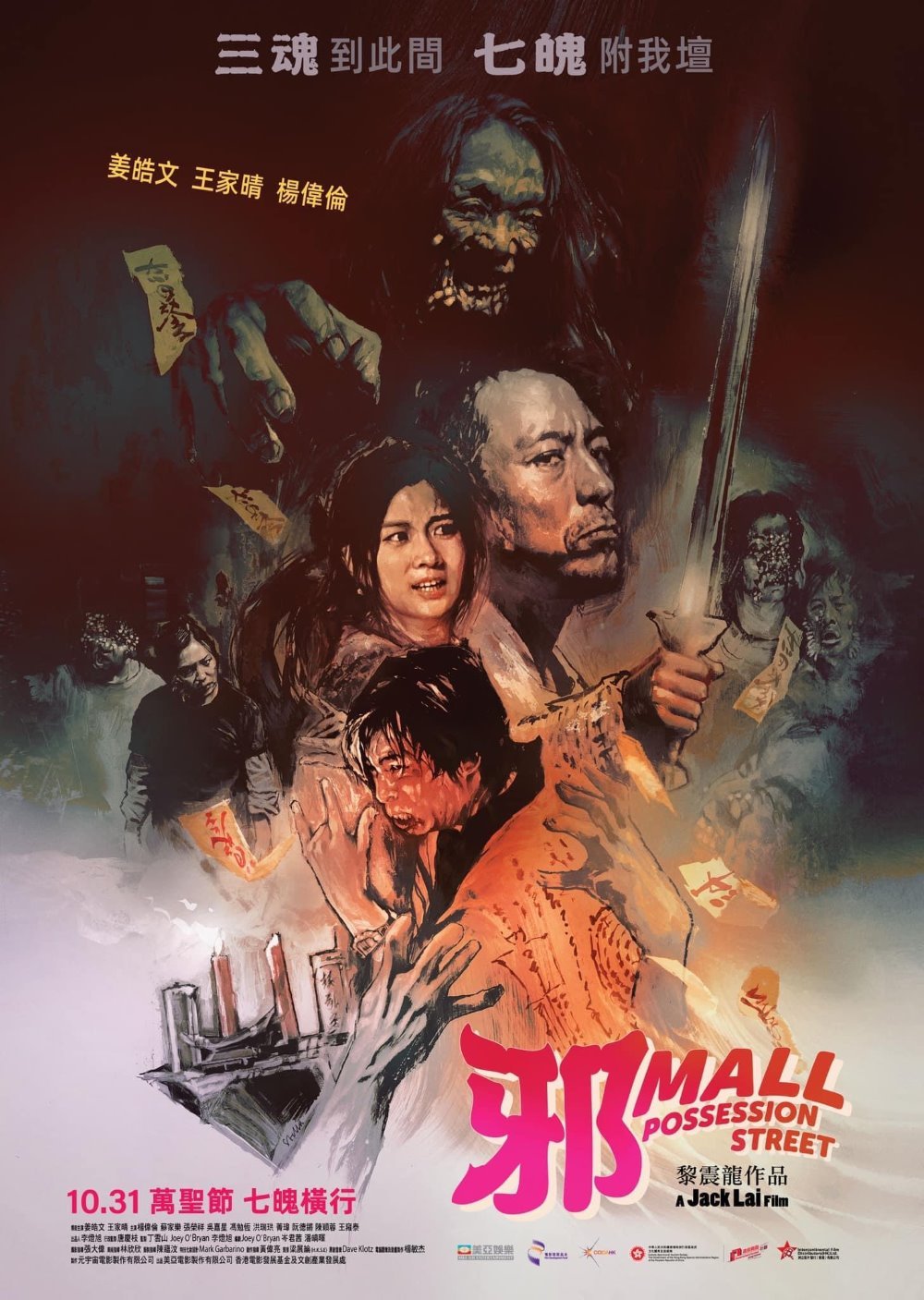

Possession Street screened as part of this year’s Focus Hong Kong.

Trailer