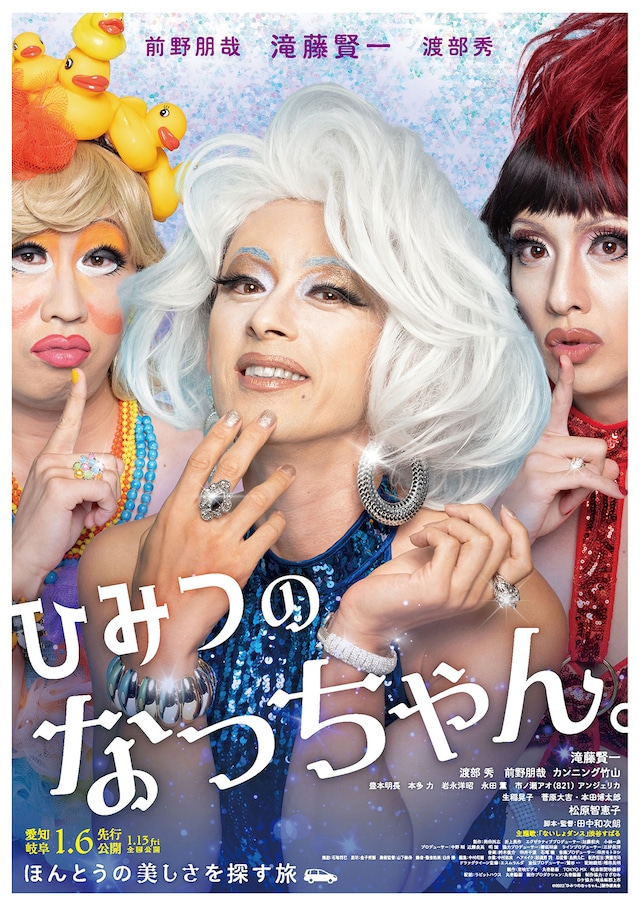

On learning that their friend and mentor has died, a trio of drag queens vows to do whatever it takes to fulfil her wishes and ensure her family never know about her sexuality in Yasujiro Tanaka’s road trip comedy Natchan’s Little Secret (ひみつのなっちゃん。, Himitsu no Natchan). In some ways it may seem old-fashioned, that rather than ensuring her family knew who she really was they decide to honour Natchan’s desire for secrecy but nevertheless meditate on the nature family while finally landing on a poignant sense of loss for all that secrecy entails.

Virgin (Kenichi Takito), an accountant by day and former drag queen who’s lost the taste for dancing, and Morilyn (Shu Watanabe) who works at the bar Natchan owned, are forced to confront the fact that in many ways they didn’t even know Natchan at all. They don’t know her address or hometown and have only the vague idea that she was estranged from her family. Virgin reflects that she was “secretive”, but in the end none of them really know what to do now that she’s gone. Another drag queen turned TV celebratory, Zubuko (Tomoya Maeno), laments that some take their secret to their grave realising that’s exactly what Natchan has done. That’s one reason why the trio become obsessed with the idea of cleaning out Natchan’s flat to make sure that her family don’t find anything they weren’t expecting.

But then again, the trio frequently refer to the gay community as their family while claiming Natchan as their own. Without really thinking about it, Morilyn allowed hospital staff to assume he was family in a more legal sense and started making funeral arrangements. He also packs up some of Natchan’s property without realising he could be accused of theft while trying to tidy up her life. They may feel that the birth family are in a sense intruding, reasserting ownership over someone they never accepted in life and preventing those who truly loved them to honour their wishes. Yet Natchan’s mother (Chieko Matsubara) turns out to be sweet old lady who is in her way hurt that she and her son became estranged wishing that they could have been closer while he was alive.

It’s she who eventually invites them to Natchan’s rural hometown which is famous for a particular kind of festival dance. None of them are sure they want to go, partly because they fear accidentally blowing Natchan’s cover but also the social attitudes of what they imagine to be a more conservative, traditional area. Only it appears quite the reverse is true. Residents at the inn where they stay actually have a fierce curiosity about drag and enthusiastically enjoy a risqué routine performed by Morilyn and Zubuko while even a manly man later shrugs his shoulders and claims it’s not so different from Gujo Odori which also makes people sparkle.

Maybe Natchan’s little secret is that she was a person who had learned to see the beautiful things in life and wanted others to see that they were beautiful too even if some told them that weren’t or they didn’t feel that they were. Virgin describes Morilyn’s straightforward living as a beautiful thing, especially as he recounts being made to do karate by conservative parents afraid of what the neighbours would think of their effeminate son, an experience he describes as emotionally destabilising and has led to a degree of repression as an adult. Virgin is out at work and well liked by a collection of female colleagues but now only dances alone at home and keeps it as her own kind of secret. Yet through their various adventures on the road the trio begin to come to new acceptances of themselves as they prepare to say goodbye to Natchan while comically affecting the tropes of conventional masculinity in an attempt not to give the game away. They wander through queer spaces in search of her and rediscover their own sense of family realising that they did know Natchan after all or at least all that was important to know as did others even if they pretended not to because that seemed to be how she wanted it. Finding liberation amid the Gujo Odori, the trio finally say goodbye but also discover a new sense of solidarity and self-acceptance joining the dance at which all truly are welcome.

Natchan’s Little Secret screened as part of this year’s Camera Japan.

Original trailer (no subtitles)