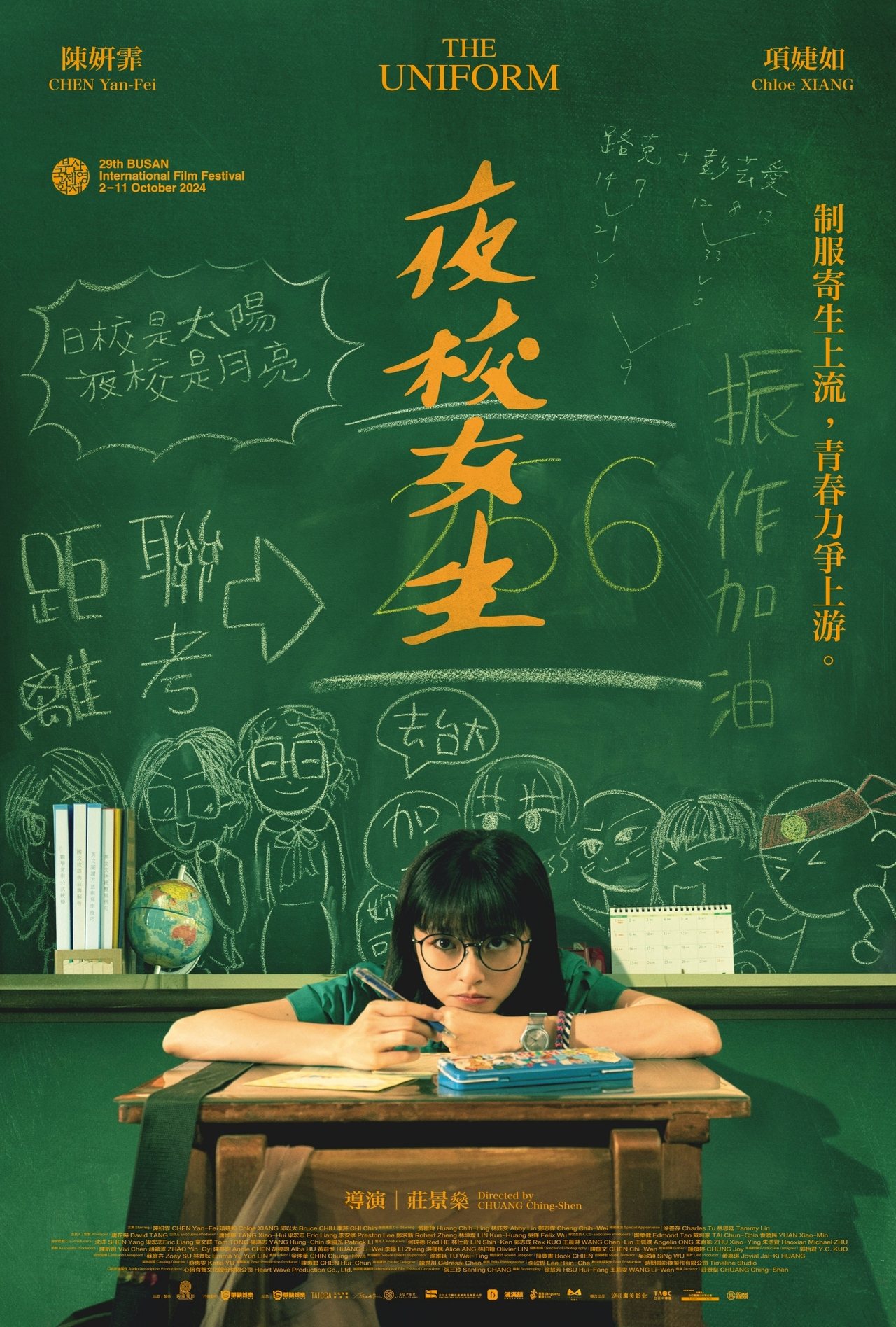

The problem for Ai (Buffy Chen Yan-fei) is that a minor difference in her uniform causes her to be treated differently. Set in the late ‘90s, Chuang Ching-Shen’s The Uniform (夜校女生, yèxiào nǚshēng) uses the school to examine the stratified nature of the contemporary Taiwanese society and the elitism that governs it. Having failed the main exam, Ai has won a place at a prestigious girls academy but been relegated to the “night school”. To maximise its efficiency, the school operates on a shift system with day pupils attending classes until 4.30pm and the night students taking over until 9. Though there isn’t supposed to be any difference between the two, the night students are treated as a kind of overflow intake and looked down on by the day pupils while some complain that they’re unfairly using up resources which should be theirs by right.

Despite the differences between them, Ai strikes up an unexpected friendship with a day student with whom she shares a desk, Min (Chloe Xiang Jie-ru). Shy and somewhat timid, Ai is taken by Min’s free spiritedness and often skips out on her classes to do fun things with her like going to a club to see Mayday before they were famous. Min, obviously, never misses out on her education and though she later reveals her own sense of insecurity in not feeling that she fits in at the school nor really deserves to be there, does not really understand Ai’s situation nor her own feelings of frustration and futility. Ai, meanwhile, is attracted by the upper-middle class atmosphere of the day pupils and increasingly embarrassed by her own more humble home life.

Ai’s father died in an accident and her mother runs a cram school out of their home. Ai’s mother (Chi Chin) is always trying to save money and picking up mismatched furniture for free, much to Ai’s annoyance, while Ai also does a series of part-time jobs including working at a ping pong club at the weekend though her mother doesn’t really want her doing sports because they’re unladylike and not all that useful for landing a place at a top university. The reason she sent her to the academy was to give her a leg up into what she sees as a conventionally successful life by getting a degree and finding a man with a professional job to marry. Ai’s resentment is partly provoked by this sense of being railroaded towards a future she might not want while at the same time facing tremendous pressure and afraid that in the end she won’t be able to measure up to her mother’s expectations.

It’s at the ping pong club that she first meets Luke (Chiu Yi-tai), a handsome student from the elite boys’ school, and begins to strike up a relationship with him before Min tells her she likes him too. This ordinary teenage love triangle is coloured be class conflict in which Ai doubts she has the right to go after Luke because he is from a wealthy family, lying to him to cover up the fact that she and Min skip school by swapping their shirts which are embroidered in different colours for day and night students by claiming to be a pupil in the elite advanced class while hiding from him that she’s actually a night pupil. After beginning to suspect that Luke might actually like Ai, Min too begins to look down on her as if she thought that Ai were forgetting her place and has no right to date him because, unlike her, she is not his social equal.

As for Luke himself, he’s actually rather bland and in part because his own life seems so easy because of his family’s wealth though he too later lets slip that he feels embarrassed by his parent’s apparently secret divorce and has only just begun to let go of the idea of them getting back together. For much of the film, it seems like he’s merely in the way of the relationship between the two girls which more successfully overcomes the barrier of class. After vicariously enjoying living Min’s lifestyle, Ai eventually comes to realisation that she and Luke are “not the same” and come from different worlds. He doesn’t really care about that, and seems to have become aware of his privilege abandoning a plan to get into university by competing in the maths olympiad and take the exam instead in the interests of “equality,” which is a well-meaning gesture but not really the bold act of egalitarianism he thinks it is even if also emphases his commitment to Ai in his willingness to break down class barriers that might otherwise work to his advantage.

As a means of denying her reality, Ai escapes through writing letters to Nicole Kidman with the help of a young man who speaks English and works in her aunt’s video store but is eventually jolted into adulthood by a more literal earthquake that reminds her how precious each of her relationships is and fragile the world around her. Through her various friendships, Ai comes to understand that almost everyone she knows also suffers with feelings of inferiority or a lack of confidence, weighed down by the pressure to achieve social success which might not be what they want anyway, but that they can overcome them together through understanding and mutual support that crosses class boundaries. Charmingly nostalgic, the film has a sense of hope for the future that it is indeed possible to achieve success on your own terms while prioritising your friendships and taking care of those around you.

The Uniform screens in Chicago 12th April as part of the 19th edition of Asian Pop-Up Cinema.

Trailer (English subtitles)