“Mama, why wasn’t I born in America?” a salesman promoting a programme bringing women from China to give birth in the US so that their child will have citizenship rather manipulatively states in an almost certainly made-up quote from a child jealous of another’s life of baseball playing freedom abroad. The never quite explained mystery at the centre of Leslie Tai’s documentary How to Have an American Baby is why exactly so many families find US citizenship so desirable given that they have no immediate intention of living there themselves.

A father later suggests that he was looking for “security”, perhaps implying a sense of anxiety regarding the future direction of China while others insist they want their kids educated in the US presumably to take advantage of more global opportunities (additional press materials also suggest a desire for a legal security not afforded to children born out of wedlock). But it’s also true that the US has shockingly high maternal mortality rates in comparison to the rest of the developed world and that, though it seems they may not have realised it, these women are risking their lives and the lives of their unborn children undergoing an incredibly stressful and difficult period of confinement and later medical procedure usually alone and unable to speak the language. Most of the women appear to be under the care of Mandarin-speaking doctors, yet their manner is often rough and unkind while at least one woman seems to suspect that the advice she’s being given may not be impartial. As non-residents who do not have medical insurance, the parents assume that the hospitals are taking advantage of the Chinese patients and charging whatever they like with rates far higher than locals would typically pay.

One could therefore say that this is a very circular business. The hospitals make their money and they’re happy, while a small industry seems to have arisen with Chinese migrants running maternity hospitals to facilititate this practice. However, largely unable to speak English themselves, they can offer little help in a crisis and as they are operating in a legal grey area are not keen to get involved in any disputes. One woman, Lele, who unfortunately loses her baby she suspects as a result of medical malpractice is kept isolated from the other mothers and given almost no support. In the lengthy birth scene in which one mother undergoes a difficult labour lasting more than a day, the director is called away to translate for Lele with alarming warnings about a baby “coding” and that there is something wrong with their heartbeat all of which only places further stress on the mother giving birth who worries that her own anxiety is the reason the delivery is taking so long.

Meanwhile, alarm is being raised by residents of the local area in which many of these “maternity hotels” are situated. They complain about increased traffic and noise due to the fact that ordinary family homes are now being used for a commercial purpose though one woman’s suggestion that they report such an innocuous sound as a baby crying (incorrectly assuming the women are also giving birth at the hotel) could obviously have unintended consequences and speaks to a greater degree of ingrained prejudice. A local government representative suggests that beyond instituting checks to ensure building safety there isn’t much they can do as the hotels aren’t breaking any laws or occupancy rules and even if they were they’d just pay someone to lease another property under a different name and set up somewhere else.

As the salesman had suggested, for some of the women US citizenship is a status symbol and something they’re made to feel they’re denying their children if they chose to give birth to them at home. This process is expensive, and many of the families lead lives far more materially comfortable in China than they likely would in the US yet they see US citizenship as something that will be extremely beneficial to their children and so naturally want to give them the best if also securing their own status in being able to give it to them. Perhaps as one man at the neighbourhood meeting suggests, it’s only “smart” to take advantage of this obvious business opportunity but it’s also true that it’s the families who are perhaps being exploited in being missold a safe and easy path to engineering future possibility for their as yet unborn children.

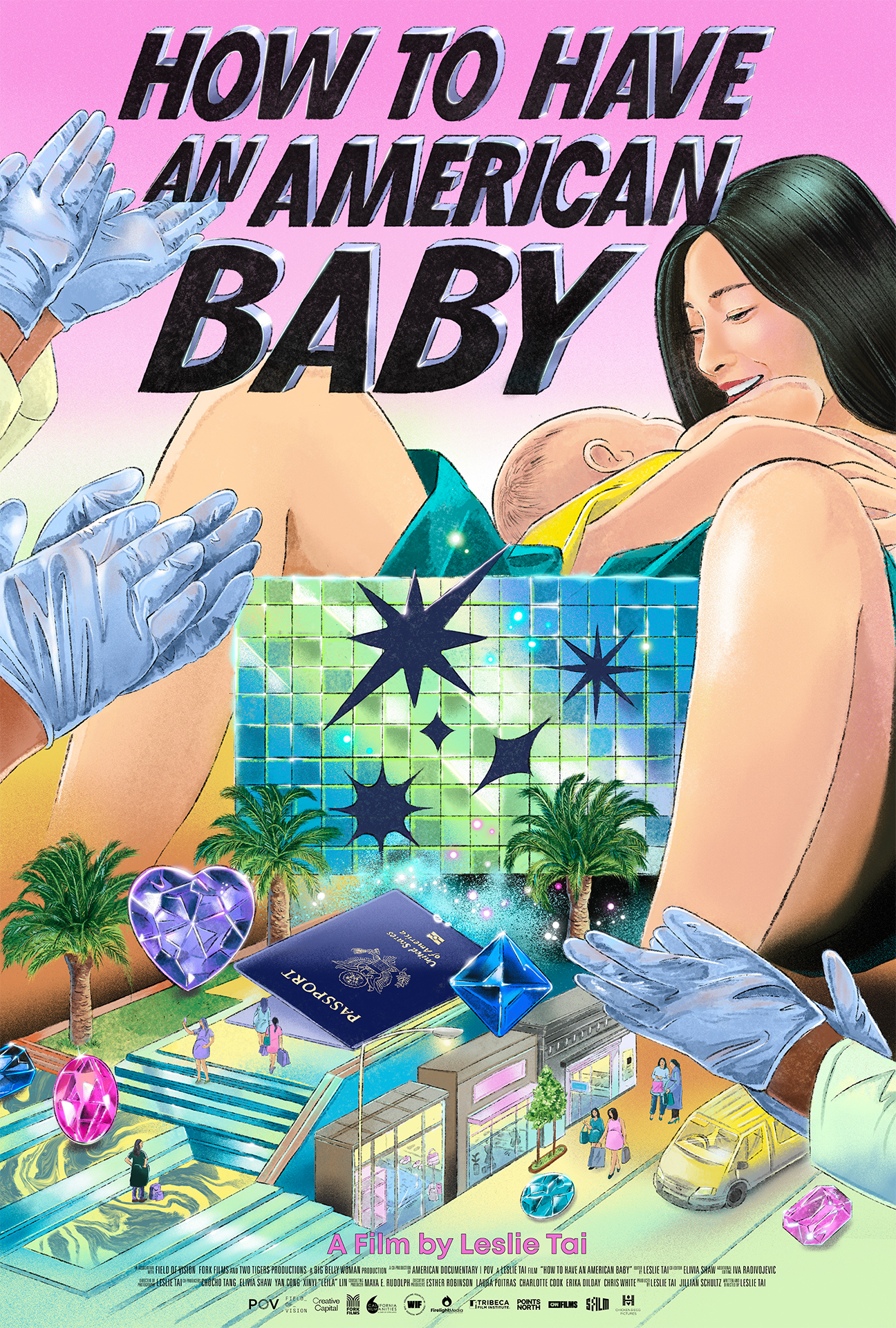

How to Have an American Baby screens Nov. 14 as part of DOC NYC and will be available to stream in the US until Nov. 26 before making its broadcast premiere on Dec. 11th on POV.

Original trailer (English subtitles)