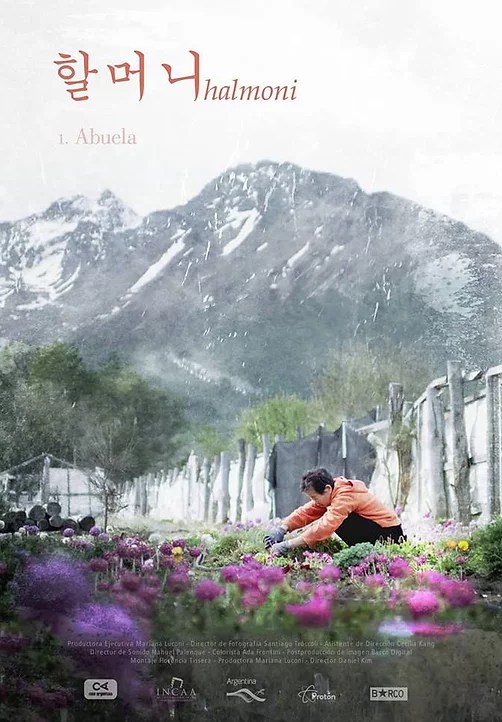

A Korean grandmother creates a paradise amid the arid lands of Argentina in Daniel Kim’s personal documentary, Halmoni. Underneath the film’s title, the Spanish translation, Abuela, appears hinting at the duality of cultures which the director contemplates while examining the longterm effects of the migration on his family who seem to console themselves with the notion that home is a place where you “live with a fully belly” while his grandmother finds a reason to live in the cultivation of land, planting flowers that will bloom long after she is gone.

Kim’s grandparents married during the chaos of the Korean War and migrated to Argentina after a fire claimed the school where his grandfather had been working as a teacher. Travelling firstly to Brazil, the family then came to Argentina and received land from the government with a plan of growing lettuce which was otherwise thought unsuited to the terrain though grandfather was confident he could make it work after seeing fields of chicory growing in the same area. Though there have apparently been some problems with money and ownership, the farm now appears large and successful with the family still working it, the grandmother explaining that work keeps her alive and gives her life both rhythm and meaning.

Yet it’s obvious that life there has not been easy. The land and farmhouse are very remote and when the family first arrived, there was not even a road that led to it. The grandfather and his son made one themselves while the son was later forced to give up on his education in Buenos Aires to help his family run the farm. As we later discover both men later took to drink in disappointment with their lives and eventually died of it. The women of the family who have largely kept the farm going also complain about the extreme cold and heavy snow which further isolate it and trap them in a liminal place that is both Korea and Argentina and simultaneously neither.

The daughter suggests she’d rather be in Buenos Aires, but when she’s in Buenos Aires all she thinks about is the farm. Later in the film, the grandmother travels to Korea for the first time in 23 years and is moved on realising that she no longer recognises her now middle-aged nephew. Many of her friends and remaining family members encourage her to return to Korea, but she points out that her children and grandchildren are all settled in Argentina while the cultures have become so blurred for her that she lives moment to moment not always sure of what is Korea and what is Argentina. Another woman later says something similar but in Spanish, that if she were to go to Korea she doesn’t think she would feel Korean but neither does she feel Argentinian in Argentina and does not know where she is from.

Yet the grandmother’s friends also worry for her when she tells them that despite her long years of hard work she has no savings while those who migrated to America or stayed in Korea were often able to find financial stability that will accompany them into old age. Kim briefly includes a scene from home video in which one of the children angrily challenges the grandfather and accuses him of misusing money while also raising some kind of religious dispute which receives no further explanation but hints at a buried resentment and discord within the family which is otherwise absent from the cheerful footage of them celebrating a wedding and coming together with other members of the Korean community. Meanwhile the government is said to have taken back half of their land when the farm experienced financial difficulty and that it was the inability to finish what his father had started that later drove the son to drink. Even so another of the women hurriedly finishes her tea worried that people watching the film will assume they are lazy while a man behind her counters that they should show them that they rest too. The grandmother tells her granddaughter about planting seeds and that some flowers must disappear so that new ones can grow as she patiently tends to her orchards, a hard-won paradise forged in arid land by little more than love and perseverance.

Halmoni screens at the Korean Cultural Centre, London on 4th August as part of Korean Film Nights 2022: Living Memories.