A changing China tries to recapture its sense of possibility by regaining its reputation as a ping pong powerhouse in Deng Chao and Yu Baimei’s rousing table tennis drama, Ping Pong: The Triumph (中国乒乓之绝地反击, Zhōngguó Pīngpāng zhī Juédì Fǎnjī). China can lose at any other sport, but not ping pong according to one aggrieved player making a dramatic return to the national team and echoing a sense of resurgent energy even as embattled coach Dai (Deng Chao) struggles to convince those around him that China can prevail.

As the film begins, Dai is an exile living in Rome and training the Italian national team. He has fully acclimatised to the comparatively relaxed Italian society, is dressed in a stylish tailored suit and wool overcoat, and has a fashionable European haircut. But to some, including it seems an institutionally racist police force, he’ll always be an other as he discovers on trying to report a mugging but ending up getting arrested himself and questioned by a cop who doesn’t like it that he’s wearing an expensive watch. With his wife heavily pregnant, Dai decides to return home to China but is offered only an assistant coaching job and given a pokey flat that doesn’t even have its own bathroom in contrast to the spacious house the family were living in in Rome while the Chinese national team flounders in an ongoing decline.

Dai’s fortunes in Italy play into the persistent message of contemporary mainstream Chinese cinema that there are no safe places for the Chinese citizen outside of China and that the only solution is to return home as soon as possible, while it’s also clear that his Westernisation is portrayed as a kind of bourgeois decadence that must eventually be corrected. On return to China, Dai continues to dress in his Italian suit rather than the team tracksuits worn by the other coaches until he’s fully reassimilated into the team and he’s even at one point criticised for spending too much time on his hair that could better be spent on training. Nevertheless, as he later points out they’re being beaten by European teams who are often trained by Chinese coaches who like him decided to chase their fortunes abroad in the confusions of early ‘90s China.

A lengthy sequence near the film’s beginning suggests that the Chinese players feel the game has been taken away from them unfairly, that though they did not invent ping pong, it has become so integral to the Chinese identity that its loss strikes at the heart of the nation’s vision of itself. Afraid of China’s success, international nations conspired to effect the restriction in trade of a special kind of glue China used for paddles while modifying the rules so that they were more in favour of taller European players rather than small and speedy Chinese sportsmen whose techniques are no longer a fit for the contemporary game. Dai’s battle is partly to force change among traditionalists and convince them that China needs to up its game to meet international competition if it is to reclaim its sporting crown.

It’s tempting to read the film as an allegory for China’s current economic ambitions if also a look back to a time of defeat in which the nation righted itself and became champions once again through unity, hard work, and faith in the future. The message is rammed home in the final pep talk Dai gives to a nervous player whose wealthy family disapprove of his choices and regard him as an embarrassment, reminding him that while their Swedish rivals took time out for holidays, sleeping, and eating breakfast they trained every minute of every day and he should learn to trust in that when faced with the seemingly insurmountable mountain of the European champion. Another player is told that he could lose the use of his arm if he continues playing but does so anyway (and is later fine), while it’s clear that Dai has made sacrifices which have strained his familial relationships in spending so much time away from his wife and young son.

There’s also a subtle current of less palatable national unity in Dai’s wife’s claim that their son is slow to speak not only because his father is away so often but that he’s surrounded by too many different dialects and it’s impeding his development, making an uncomfortable argument for the primacy of standard Beijing-accented Mandarin. Nevertheless, the message is fairly clear in the frequent cut backs to young children watching the games and once again seeing China on the world stage, gaining a new sense of possibility for their own lives in the vicarious success of sporting championship. Deng and Yu shoot the matches with breathless intensity and an unexpected immediacy as the ball seems to barrel through the camera, and at one point takes the place of the star on the Chinese flag. “Chinese are the most diligent” Dai reminds his player, certain that they will get there in the end through sheer force of will, hard work, personal sacrifice for the national good, and above all togetherness as they battle seemingly insurmountable odds to reclaim their sporting crown and with it a national identity.

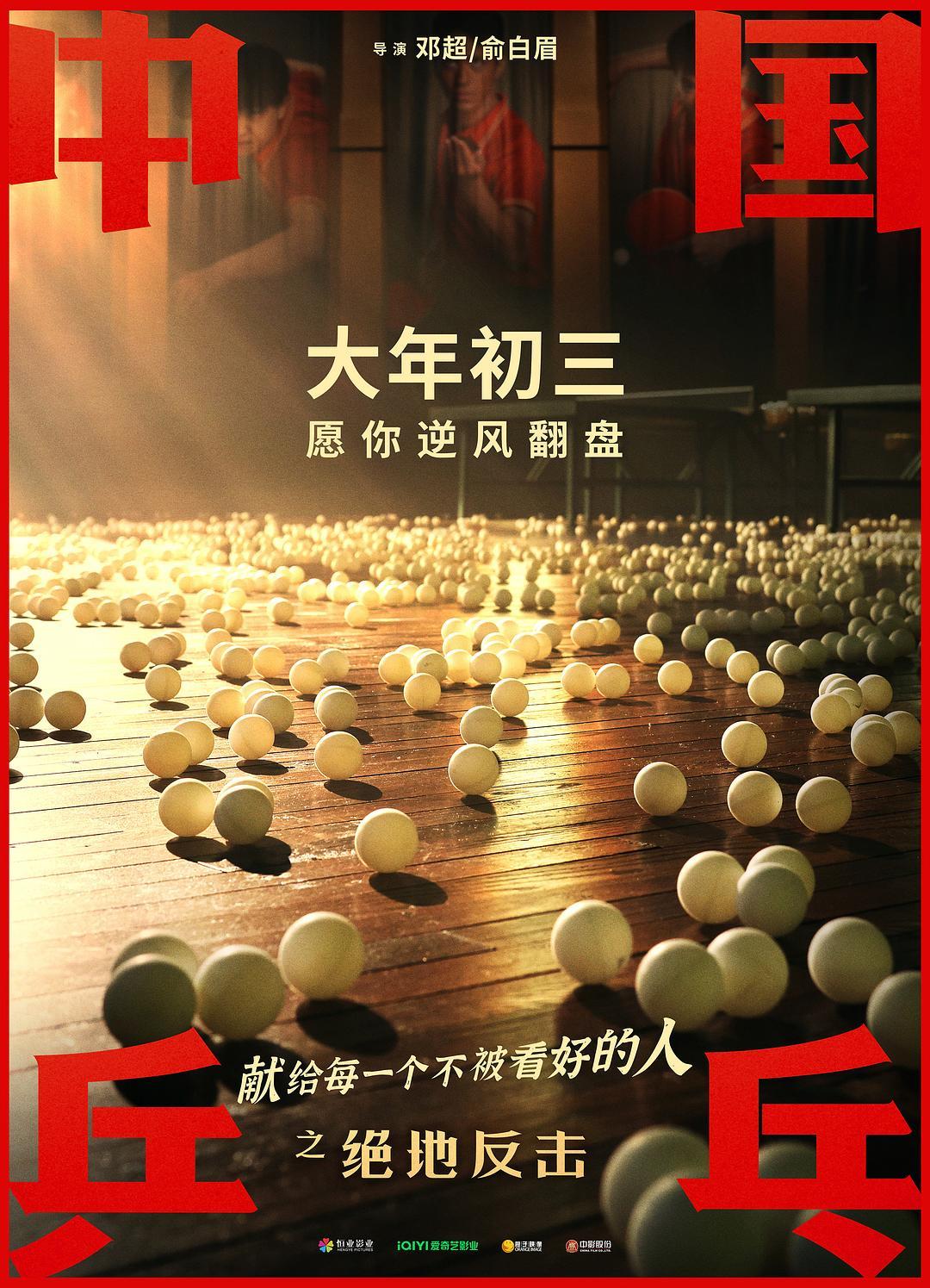

Ping-Pong: The Triumph screens in Chicago March 25 as part of the 16th season of Asian Pop-Up Cinema.

Original trailer (Simplified Chinese / English subtitles)

It’s difficult not to read every film that comes out of the Mainland as a comment on modern China but there does seem to be a persistent need to address the rapid changes engulfing the increasingly prosperous society through the medium of cinema. A or B (幕后玩家, M

It’s difficult not to read every film that comes out of the Mainland as a comment on modern China but there does seem to be a persistent need to address the rapid changes engulfing the increasingly prosperous society through the medium of cinema. A or B (幕后玩家, M