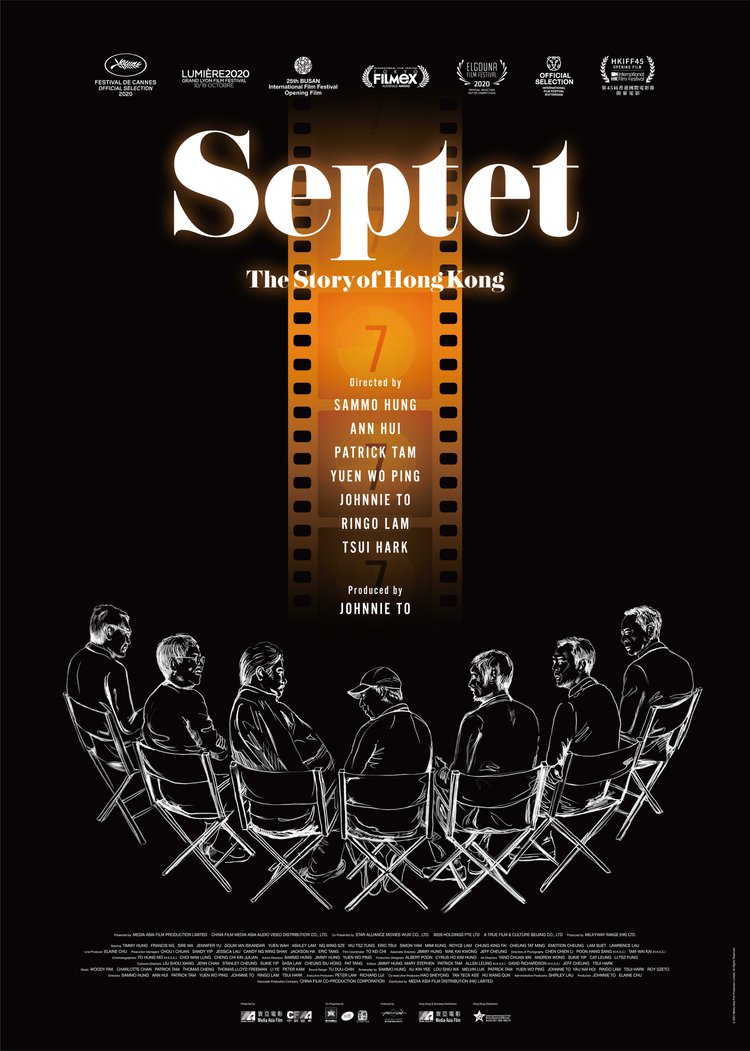

Seven of Hong Kong’s most prominent directors come together for a collection of personal tales of Hong Kong past and present in the seven-part anthology film, Septet: The Story of Hong Kong (七人樂隊). Produced by Johnnie To’s Milky Way, the film was first announced several years ago and originally titled Eight & a Half though director John Woo sadly had to leave the project due to his wife’s ill health which explains why there is no short set in the 1970s.

Each of the segments reflects the director’s personal nostalgia for a particular moment in time and there is certainly a divide between the 1950s and 60s sequences directed by Sammo Hung and Ann Hui respectively and those of the 80s and 90s which are imbued with a sense of Handover anxiety along with the closing meditation on the various ways the city has or has not changed. In any case, Sammo Hung’s opener Exercise is a slice of personal nostalgia which looks back to the heyday of Hong Kong kung fu as the young Sammo learns to buckle down and train with discipline under the guidance of his authoritarian teacher played by his own son, Timmy Hung. Similarly education-themed, Hui’s Headmaster echoes the documentary aesthetic seen in the later stages of Our Time Will Come in her naturalistic capture of a primary school reunion taking place in 2001 before flashing back to the early ‘60s as the headmaster and the children reminisce about a kind and idealistic young teacher who sadly passed away at 39 from a longterm illness exacerbated by misapplied traditional medicine. Essentially a tale of old-fashioned reserve in the unrealised desires of the headmaster and the teacher who elected not to marry because of her illness in the knowledge she would die young, Hui’s gentle melodrama harks back to a subtler age.

Patrick Tam’s 80s segment, Tender is the Night, perhaps does the opposite in its incredibly theatrical tale of love thwarted by political realities as a lovelorn middle-aged man looks back on the failure of his first, and last, love for the teenage girlfriend who like so many of that time emigrated with her parents to escape Handover anxiety. Rich in period detail and imbued with the overwhelming quality of adolescent emotion, Tam’s maximalist romance is a tale of love in the age of excess but also of middle-aged nostalgia and personal myth making which nevertheless positions the looming Handover as a point of youthful transition.

The 1997 sequence itself, Homecoming directed by Yuen Wo-ping, is in someways subversive in again presenting a young woman who firmly believes her future lies abroad rather than in post-Handover Hong Kong and placing her at playful odds with her traditionalist grandfather, a former martial arts champion who spends his days watching old Wong Fei-Hung movies. The eventual resolution that the girl, who insists on going by her Western name Samantha, returns to Hong Kong a few years later to care for the grandfather who has aged quite rapidly undercuts the sense of anxiety, yet there is something in the cultural and generational conflict that exists between them eased by mutual exchange as she teaches him basic English and he teaches her kungfu that hints less that the traditional is better than the modern than that there’s room for both hamburgers and rice rolls.

Moving into the 2000s, Johnnie To’s Bonanza then takes aim at the increasingly consumerist mindset of the contemporary society in picking up a theme from Life Without Principle as three young Hong Konger’s become obsessed with getting rich quick through financial investment beginning with the dot-com bubble and shifting into property profiteering during the SARS epidemic. The trio fail every time before hitting the jackpot with some shares they bought by mistake during the 2008 financial crisis suggesting that it all just luck after all. One of the guys comically switches business opportunities in line with each of the crises/opportunities, firstly getting into mobile phones, then peddling healthcare products, and finally investing in self-storage in an echo of his society’s scrappy entrepreneurial spirit.

The final film from Ringo Lam who completed his segment Astray shortly before passing away 2018 continues the theme in meditating on the modern city as its hero is literally killed by a sense of cultural dislocation after getting lost in a very changed Hong Kong having emigrated to the UK and returned with his family for a New Year holiday. While ironically remembering his own father complaining that times had changed, he finds himself bewildered by the absence of familiar landmarks and adrift in his home city. He dreams another life for himself in the countryside in which his son decides to emigrate to America while his wife would prefer he find a job in Hong Kong but his final message to him that it’s not difficult to live happily perhaps frees him of the sense of nostalgia which has led to his father’s death.

The best and final episode, however, Tsui Hark’s Conversation is set at no particular time and my in fact take place in the future as a mental patient, who might actually be a doctor pretending to be a mental patient, suddenly gives his name as Ann Hui followed by Maggie Cheung and a string of Hong Kong directors from Ringo Lan to Jonnie To and John Woo and challenges the doctor, who might be a mental patient, as he struggles to keep up with him. Tsui and Hui make reflective cameo’s at the segment’s conclusion perhaps hinting that this has been a deep conversation with the history not only of Hong Kong but its cinema through the eyes of those who helped to make it what it is.

Septet: The Story of Hong Kong screens in Chicago on Nov.6 as part of the 15th season of Asian Pop-Up Cinema.

Original trailer (English subtitles)