“Reality’s too stupid to cry over” affirms the deadpan narrator of Makoto Nagahisa’s We Are Little Zombies (ウィーアーリトルゾンビーズ), so why does he feel so strange about feeling nothing much at all? Taking its cues from the French New Wave by way of ‘60s Japanese avant-garde, the first feature from the award winning And So We Put Goldfish in the Pool director is a riotous affair of retro video game nostalgia and deepening ennui, but it’s also a gentle meditation on finding the strength to keep moving forward despite all the pain, emptiness, and disappointment of being alive.

“Reality’s too stupid to cry over” affirms the deadpan narrator of Makoto Nagahisa’s We Are Little Zombies (ウィーアーリトルゾンビーズ), so why does he feel so strange about feeling nothing much at all? Taking its cues from the French New Wave by way of ‘60s Japanese avant-garde, the first feature from the award winning And So We Put Goldfish in the Pool director is a riotous affair of retro video game nostalgia and deepening ennui, but it’s also a gentle meditation on finding the strength to keep moving forward despite all the pain, emptiness, and disappointment of being alive.

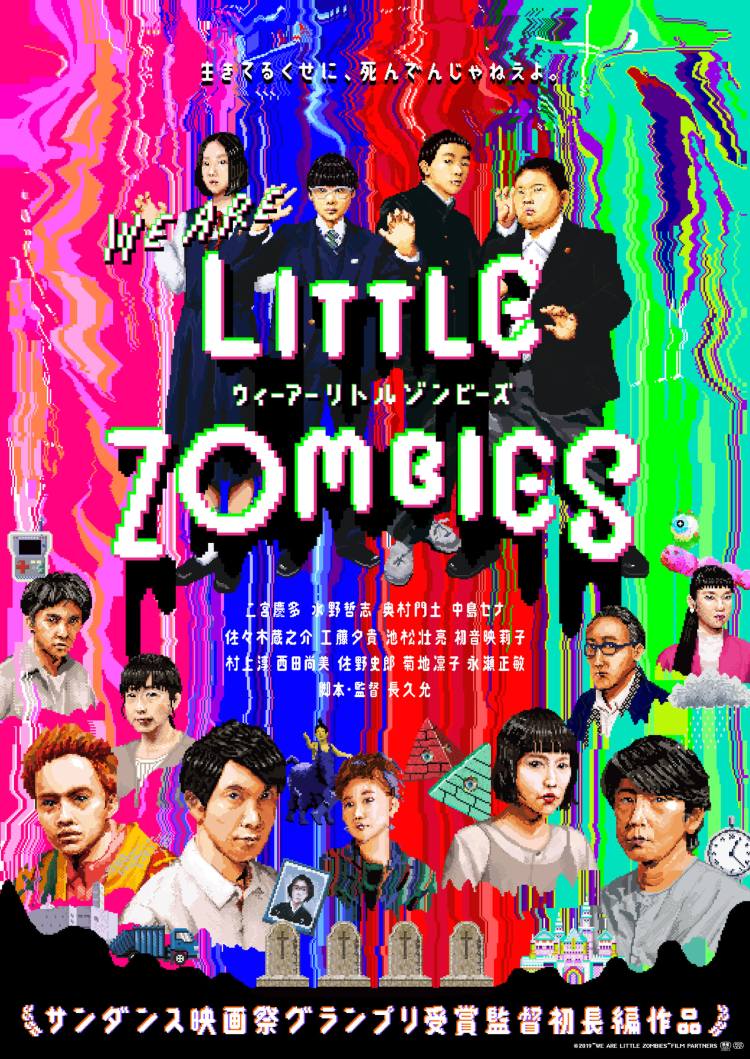

The “Little Zombies”, as we will later discover, are the latest tween viral pop sensation led by bespectacled 13-year-old Hikari (Keita Ninomiya). Recounting his own sorry tale of how his emotionally distant parents died in a freak bus accident, Hikari then teams up with three other similarly bereaved teens after meeting at the local crematorium where each of their parents is also making their final journey. Inspired by a retro RPG with the same title, the gang set off on an adventure to claim their independence by revisiting the sites of all their grief before making themselves intentionally homeless and forming an emo (no one says that anymore, apparently) grunge band to sing about their emotional numbness and general inability to feel.

Very much of the moment, but rooted in nostalgia for ages past, Little Zombies is another in a long line of Japanese movies asking serious questions about the traditional family. The reason Hikari can’t cry is, he says, because crying would be pointless. Babies cry for help, but no one is going to help him. Emotionally neglected by his parents who, when not working, were too wrapped up in their own drama to pay much attention to him, Hikari’s only connection to familial love is buried in the collection of video games they gave him in lieu of physical connection, his spectacles a kind of badge of that love earned through constant eyestrain.

The other kids, meanwhile, have similarly detached backgrounds – Takemura (Mondo Okumura) hated his useless and violent father but can’t forgive his parents for abandoning him in double suicide, Ishii (Satoshi) Mizuno) resented his careless dad but misses the stir-fries his mum cooked for him every day, and Ikuko (Sena Nakaijma) may have actually encouraged the murder of her parents by a creepy stalker while secretly pained over their rejection of her in embarrassment over her tendency to attract unwanted male attention even as child. The kids aren’t upset in the “normal” way because none of their relationships were “normal” and so their homes were never quite the points of comfort and safety one might have assumed them to be.

Orphaned and adrift, they fare little better. The adult world is as untrustworthy as ever and it’s not long before they begin to feel exploited by the powers intent on making them “stars”. Nevertheless, they continue with their deadpan routines as the “soulless” Little Zombies until their emotions, such as they are, begin inconveniently breaking through. “Despair is uncool”, but passion is impossible in a world where nothing really matters and all relationships are built on mutual transaction.

Mimicking Hikari’s retro video game, the Zombies pursue their quest towards the end level boss, passing through several stages and levelling up as they go, but face the continuing question of whether to continue with the game or not. Save and quit seems like a tempting option when there is no hope in sight, but giving in to despair would to be to let the world win. The only prize on offer is life going on “undramatically”, but in many ways that is the best reward one can hope for and who’s to say zombies don’t have feelings too? Dead but alive, the teens continue their adventure with heavy hearts but resolved in the knowledge that it’s probably OK to be numb to the world but also OK not to be. “Life is like a shit game”, but you keep playing anyway because sometimes it’s kind of fun. A visual tour de force and riot of ironic avant-garde post-modernism, We Are Little Zombies is a charmingly nostalgic throwback to the anything goes spirit of the bubble era and a strangely joyous celebration of finding small signs of hope amid the soulless chaos of modern life.

We Are Little Zombies was screened as part of the 2019 Nippon Connection Film Festival.

Original trailer (English subtitles)

Makoto Nagahisa’s short And So We Put Goldfish in the Pool

Music videos for We Are Little Zombies and Zombies But Alive