Feng Xiaogang’s films often straddle and awkward line in which it’s not entirely clear whether he’s deliberately being subversive or only unwittingly. The surprising thing about We Girls (向阳·花, Xiàngyáng·huā) is, however, its contradictory attitudes towards the modern China of which one would not otherwise assume the censors would approve. Nevertheless, the true goal appears to be paying tribute to the prison and probation service which is thoughtful and compassionate, geared towards helping these unfortunate young women who’ve made “poor choices” to reform and become responsible members of society.

But like many films of this nature, the problem is that the society the prison authorities want these women to “reform” into doesn’t exist. The onus is all on the women to change, while no attempts have been made to address the circumstances that led to them being sent to prison which are also the same circumstances they will be returning to. The women don’t appear to receive any additional education or learn any new skills while inside, and when they get out it’s impossible to find a mainstream job that will hire a woman with a criminal record. Consequently, they are forced into short-term, casual labour which is often exploitative while male employers withhold pay to extract sexual favours.

Aside from praise for the police force, the film is also a celebration of female solidarity and it’s clear that their biggest enemy is entrenched misogyny and the patriarchal society. Yuexing (Zhao Liying) is forced into a marriage with a man who couldn’t work because of a physical disability. As he resented their daughter and gave her no help with childcare, Yuexing felt responsible when the baby experienced hearing loss after contracting meningitis and was determined to save for a cochlear implant. To earn more money, she became a cam girl but was caught and sent to prison for two years for obscenity. Mao Amei (Cheng Xiao), meanwhile, is an 18-year-old deaf-mute orphan exploited by criminal gang who are sort of like her “family” but force her to steal for them.

Having learned a little sign language for her daughter, Yuxing becomes Mao Amei’s interpreter in prison, but the pair find things on the outside much more difficult than in. Apparently illiterate and unable to speak, Mao Amei cannot rent a place to stay and is caught breaking into an abandoned car. The police take pity and let her go, but also take most of the money she was given on her release. Yuexing, meanwhile, discovers her husband abandoned their daughter who is now in an orphanage but is unable to reclaim her without a stable income and permanent address. She finds a job as a hotel maid, but is falsely accused of thievery by a wealthy businessman on a power trip and subsequently fired for concealing her previous conviction. Realistically, the women have little option but to fall into criminality because there really are no other options.

Still, they’re supported by a network of female solidarity from sympathetic corrections officer Deng Hong (Chuai Ni), herself a foundling raised by a policeman, to another young girl sent to prison for reselling exotic animals off the internet. Orphanhood is a persistent theme with China’s longtime child trafficking problem ticking away in the background. The gang of thieves is eventually exposed as running a baby farm to make up for the decline in their traditional line of work thanks to digitalisation. Yuexing is faced with an impossible decision when she discovers that a wealthy couple are keen to adopt her daughter and are prepared to buy her a cochlear implant right away, knowing that it would be wrong to deny her this “better life” but also that her child has been taken away from her because of her socio-economic marginalisation and husband’s indifference.

It’s only thanks to the found family that emerges between the women because of their shared experiences that they are able to find a way through, while small acts of “foolish” kindness are later repaid in kind. To that extent, the resolution falls into the realms of fantasy as the women are saved by a deus ex machina rather than through finding a place for themselves within the contemporary society and “reforming” themselves in the way the prison service insists. In the end, they are only able to free themselves through an act of violence that comes with additional, though bearable, costs and grants them the possibility of making a new life for themselves if one spiritually and geographically still on the margins of the contemporary society.

Trailer (Simplified Chinese / English subtitles)

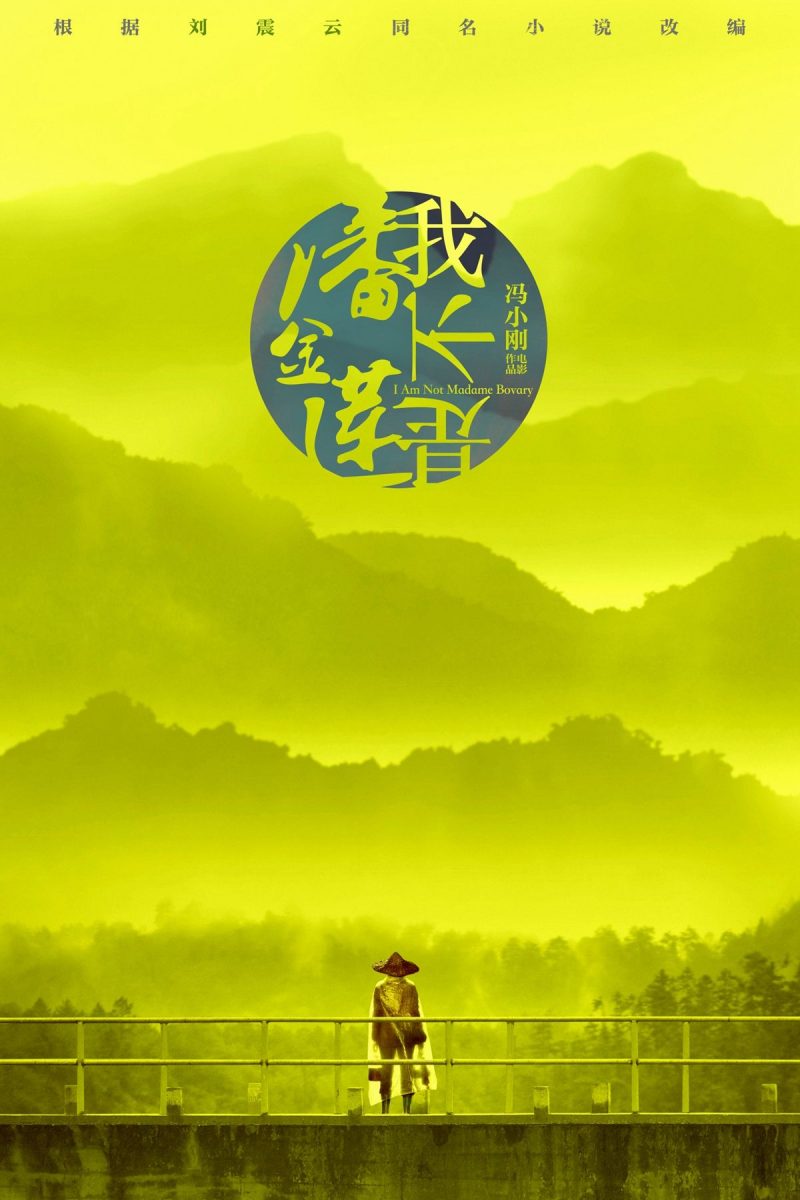

Feng Xiaogang, often likened to the “Chinese Spielberg”, has spent much of his career creating giant box office hits and crowd pleasing pop culture phenomenons from World Without Thieves to Cell Phone and You Are the One. Looking at his later career which includes such “patriotic” fare as Aftershock, Assembly, and

Feng Xiaogang, often likened to the “Chinese Spielberg”, has spent much of his career creating giant box office hits and crowd pleasing pop culture phenomenons from World Without Thieves to Cell Phone and You Are the One. Looking at his later career which includes such “patriotic” fare as Aftershock, Assembly, and