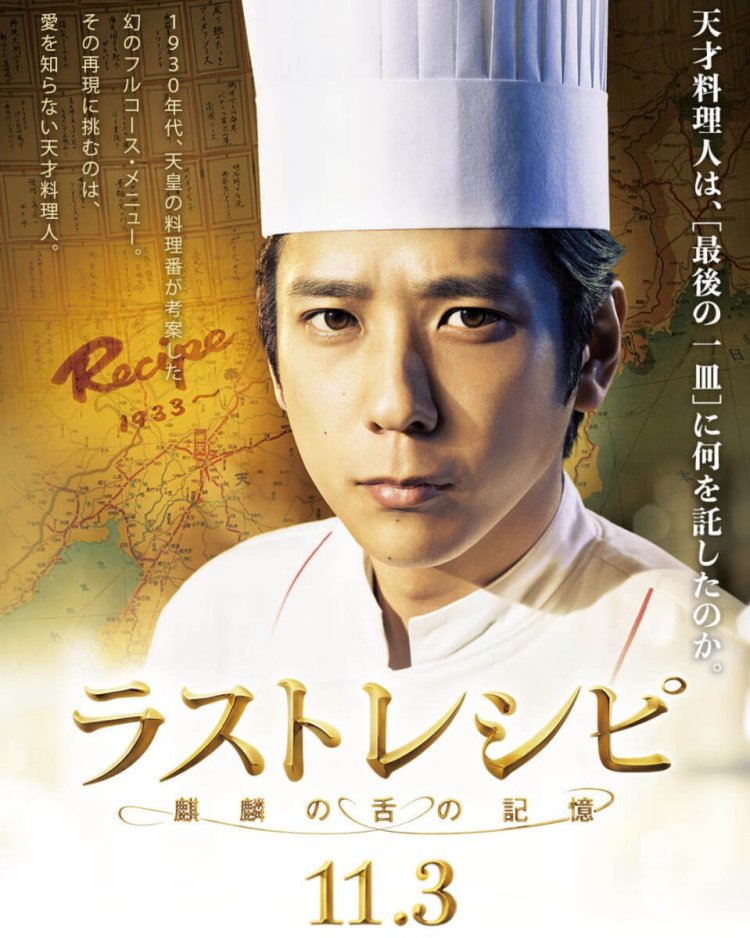

Is it really possible to be “successful” and a terrible person? Some might say it’s impossible to become successful and stay nice, but in Japanese cinema at least success is a communal effort. Prideful selfishness is indeed the reason for the downfall of the hero of Yoijro Takita’s historically minded cooking drama The Last Recipe (ラストレシピ〜麒麟の舌の記憶〜, Last Recipe: Kirin no Shita no Kioku). Adapted from a novel by the director of the Iron Chef TV show, The Last Recipe offers a somewhat revisionist portrait of Japan in the 1930s but, perhaps ironically, does indeed prove that no one gets by on their own and all artistic endeavours will necessarily fail when they come from a place of self absorbed obsession with craft.

Is it really possible to be “successful” and a terrible person? Some might say it’s impossible to become successful and stay nice, but in Japanese cinema at least success is a communal effort. Prideful selfishness is indeed the reason for the downfall of the hero of Yoijro Takita’s historically minded cooking drama The Last Recipe (ラストレシピ〜麒麟の舌の記憶〜, Last Recipe: Kirin no Shita no Kioku). Adapted from a novel by the director of the Iron Chef TV show, The Last Recipe offers a somewhat revisionist portrait of Japan in the 1930s but, perhaps ironically, does indeed prove that no one gets by on their own and all artistic endeavours will necessarily fail when they come from a place of self absorbed obsession with craft.

In 2002, failed chef Mitsuru (Kazunari Ninomiya) is eking out a living by cooking “last meals” for elderly people desperate to crawl inside a happy memory as they prepare to meet their ends. Mitsuru’s special talent is that he has a “Qilin” tongue which means that he can remember each and every dish he has ever tasted and recreate it perfectly – for which he charges a heavy fee in order to pay off the vast debts he accrued when his restaurant went bust. When a mysterious client in Beijing offers him an improbably lucrative job, Mitsuru jumps at the task but it turns out to be much more complicated than he could have imagined. His client, Yang (Yoshi Oida), wants him to recreate the mysterious “Great Japanese Imperial Feast” as designed for an imperial visit to the Japanese puppet state of Machuria in the late 1930s.

Somewhat controversially (at least out of context), Yang sadly intones that the years of Japanese occupation were the happiest of his life. Through the events of the film, we can come to understand how that might be true, but it’s a bold claim to start out with and The Last Receipe’s vision of the Manchurian project is indeed a generally rosy one even if the darkness eventually creeps in by the end. A perfect mirror for Mitsuru, the chef that he must imitate is a Japanese genius cook dispatched to Manchuria on a secret culinary mission which turns out to be entirely different to the goal he assumed he was working towards. Nevertheless, though not exactly an outright militarist, Yamagata’s (Hidetoshi Nishijima) view of the Manchurian experiment echoes that which the state was eager to sell in that he hopes to create a legendary menu that will unite the disparate cultures of the burgeoning Japanese empire under a common culinary banner, building bridges through fusion food.

Yang, his Chinese assistant, is the only dissenting voice as he points out that Japan is often keen to sell the one nation philosophy but reserves its own place at the top of the tree with everyone else always underneath. In any case, Yang, Yamagata, and his assistant Kamata (Daigo Nishihata) eventually bond through their shared love of cooking but the problems which plague Yamagata are the same ones which caused Mitsuru’s restaurant to fail – he was too rigid and self-obsessed, a perfectionist unwilling to delegate who alienated those around him and wasted perfectly good food for nothing more than minor imperfections. Yamagata’s kindly wife (Aoi Miyazaki) is quick to point out his faults, but it takes real tragedy before he is able to see that the reason his dishes don’t hit home is that he was not prepared to embrace the same communal spirit he envisioned for his food during its creation.

Mitsuru, however, is much slower to learn the same thing, decrying Yamagata as a loser who sold out and allowed his emotional suffering to turn to turn him soft, assuming this is the reason that his recipe was never completed. As expected, Mitsuru’s mission mirrors Yamagata’s in being not quite what he assumed it to be, eventually learning a few truths about himself as he gets to know the historical chef through the eyes of those who remember him. Eventually Mitsuru too comes to understand that the only thing which gives his craft meaning is sharing it and that he’s never really been as alone he might have felt himself to be. Though its vision of the Manchurian project is somewhat idealised as seen through the naive eyes of Yamagata, The Last Recipe nevertheless presents a heartwarming tale of legacy and connection in which cooking and caring for others, sharing one’s food and one’s table with anyone and everyone, becomes the ultimate path towards a happy and harmonious society.

Original trailer (English/Chinese subtitles)

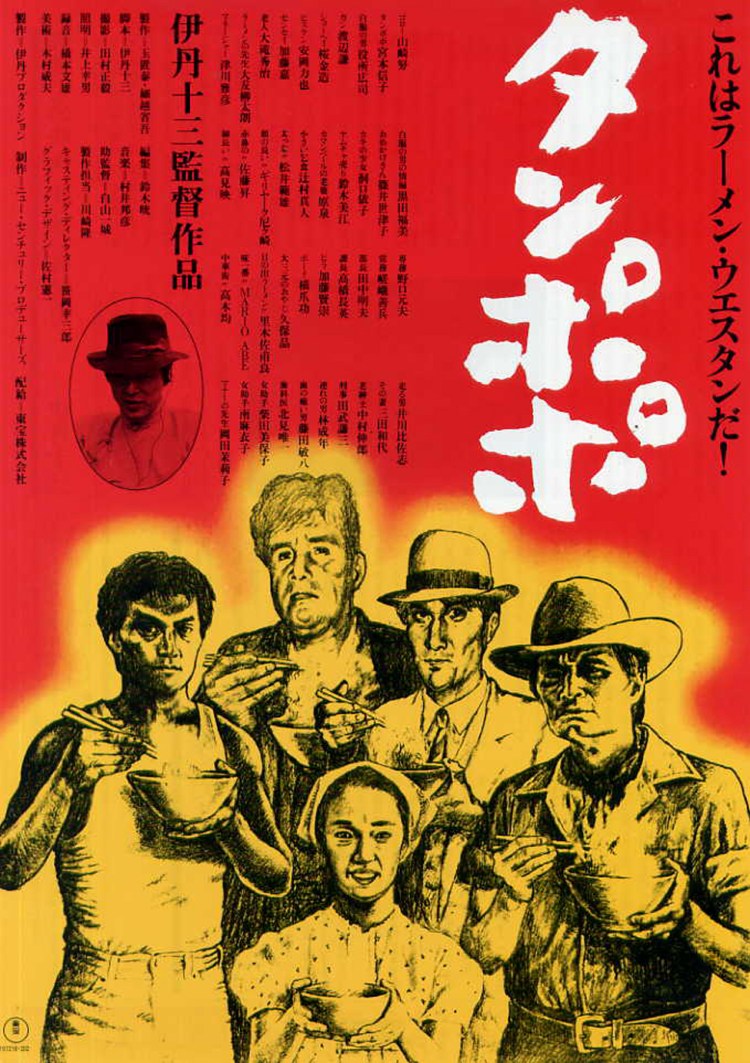

Some people love ramen so much that the idea of a “bad” bowl hardly occurs to them – all ramen is, at least, ramen. Then again, some love ramen so much that it’s almost a religious experience, bound up with ritual and the need to do things properly. A brief vignette at the beginning of Juzo Itami’s Tampopo (タンポポ) introduces us to one such ramen expert who runs through the proper way of enjoying a bowl of noodle soup which involves a lot of talking to your food whilst caressing it gently before finally consuming it with the utmost respect. Ramen is serious business, but for widowed mother Tampopo it’s a case of the watched pot never boiling. Thanks to a cowboy loner and a few other waifs and strays who eventually become friends and allies, Tampopo is about to get some schooling in the quest for the perfect noodle whilst the world goes on around her. Food becomes something used and misused but remains, ultimately, the source of all life and the thing which unites all living things.

Some people love ramen so much that the idea of a “bad” bowl hardly occurs to them – all ramen is, at least, ramen. Then again, some love ramen so much that it’s almost a religious experience, bound up with ritual and the need to do things properly. A brief vignette at the beginning of Juzo Itami’s Tampopo (タンポポ) introduces us to one such ramen expert who runs through the proper way of enjoying a bowl of noodle soup which involves a lot of talking to your food whilst caressing it gently before finally consuming it with the utmost respect. Ramen is serious business, but for widowed mother Tampopo it’s a case of the watched pot never boiling. Thanks to a cowboy loner and a few other waifs and strays who eventually become friends and allies, Tampopo is about to get some schooling in the quest for the perfect noodle whilst the world goes on around her. Food becomes something used and misused but remains, ultimately, the source of all life and the thing which unites all living things. It used to be that movies about marital discord typically ended in a tearful reconciliation and the promise of greater love and understanding between two people who’ve taken a vow to spend their lives together. These endings reinforce the importance of the traditional family which is, after all, what a lot of Japanese cinema is based on. However, times have changed and now there’s more room for different narratives – stories of women who’ve had enough with their useless, deadbeat man children and decide to make a go of things on their own.

It used to be that movies about marital discord typically ended in a tearful reconciliation and the promise of greater love and understanding between two people who’ve taken a vow to spend their lives together. These endings reinforce the importance of the traditional family which is, after all, what a lot of Japanese cinema is based on. However, times have changed and now there’s more room for different narratives – stories of women who’ve had enough with their useless, deadbeat man children and decide to make a go of things on their own. Finland, Finland, Finland. That’s the country for me! Where better could there possibly be to open up a small Japanese cafe than in Helsinki? On second thoughts, don’t answer that but moving to Finland and opening her own diner all alone is exactly what the leading lady, Sachie, has done in this warm hearted comedy drama from Naoko Ogigami, Kamome Diner (かもめ食堂, Kamome Shokudou). As in most of her films, Ogigami has assembled an eclectic cast of eccentric characters who each find themselves turning up at Sachie’s restaurant largely by chance but this time there’s a little added cross cultural pollination too.

Finland, Finland, Finland. That’s the country for me! Where better could there possibly be to open up a small Japanese cafe than in Helsinki? On second thoughts, don’t answer that but moving to Finland and opening her own diner all alone is exactly what the leading lady, Sachie, has done in this warm hearted comedy drama from Naoko Ogigami, Kamome Diner (かもめ食堂, Kamome Shokudou). As in most of her films, Ogigami has assembled an eclectic cast of eccentric characters who each find themselves turning up at Sachie’s restaurant largely by chance but this time there’s a little added cross cultural pollination too. Yaro Abe’s manga Midnight Diner (深夜食堂, Shinya Shokudo) was first adapted as 10 episode TV drama back in 2009 with a second series in 2011 and a third in 2014. With a Korean adaptation in between, the series now finds itself back for second helpings in the form of a big screen adaptation.

Yaro Abe’s manga Midnight Diner (深夜食堂, Shinya Shokudo) was first adapted as 10 episode TV drama back in 2009 with a second series in 2011 and a third in 2014. With a Korean adaptation in between, the series now finds itself back for second helpings in the form of a big screen adaptation.