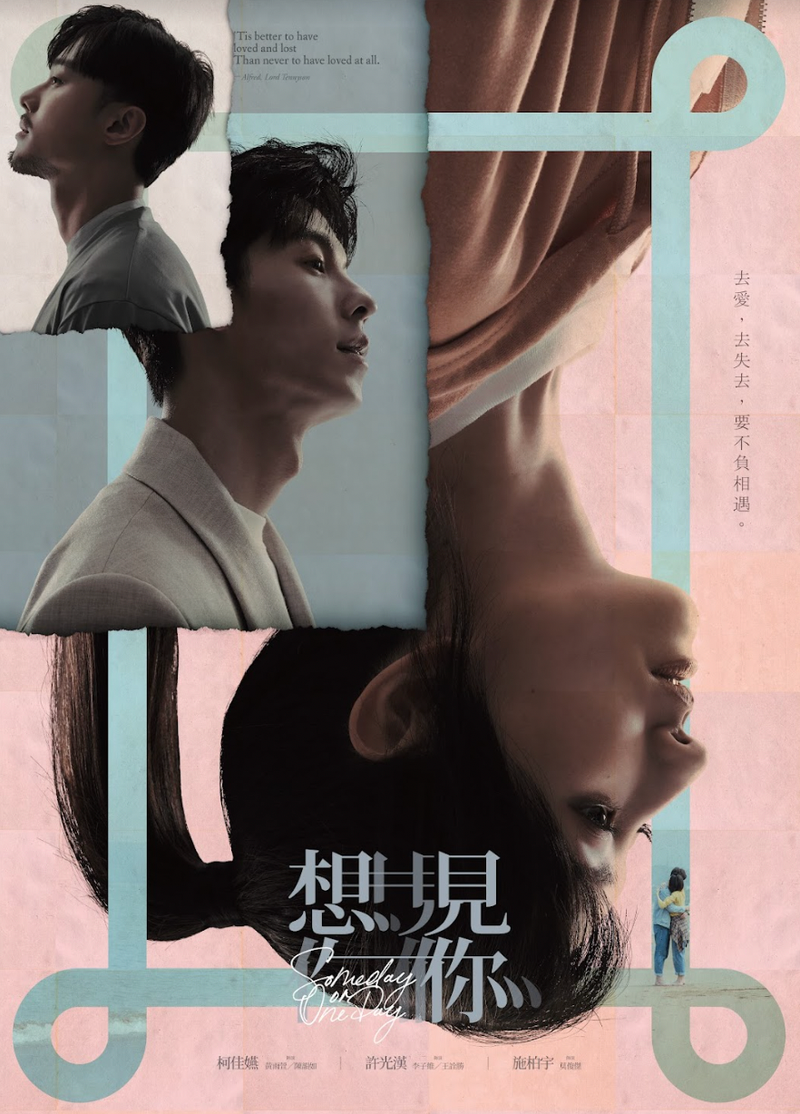

A young woman finds herself quite literally in someone else’s shoes while trying to reclaim lost love in Tien Jen Huang’s sci-fi-inflected drama, Someday or One Day (想見你, Xiǎng Jiàn Nǐ). Inspired by the hugely popular television drama of the same name and starring the same cast, this big-screen edition drops the 20-year time slip device for a comparatively compressed tale largely taking place between 2014 and 2017 while the romantically troubled heroes effectively span a kind of multiverse of heartbreak, each looking for the good timeline where both they and their love can survive together.

It has to be said, however, that the meet cute between destined lovers Yu-hsuan (Ko Chia-yen) and Zi-wei (Greg Hsu) is not without its problematic elements given that Yu-Hsuan is still in high school when the tale begins while Zi-wei is in his mid-20s, not to mention he’s largely interested in her because she looks exactly like old high school friend Yun-ru (Also Ko Chia-yen). Their meeting was brokered by a shared dream featuring the song Last Dance by Wu Bai which was released in 1996 which might explain why Yu-Hsuan didn’t know it prior to hearing it in the dream world where she lived with a man she didn’t know but turns out to be Zi-wei. The pair hit it off and eventually move in together. They are blissfully happy until Zi-wei is killed protecting Yu-Hsuan when they both randomly fall from a building which is still under construction.

What they were doing there in the first place isn’t really explained, but it doesn’t become the nexus of Yu-hsuan’s trauma as she struggles to move on with her life continuing to communicate with Zi-wei through text message and imagined conversation even after moving to Shanghai for work. After being sent a walkman and cassette tape of The Last Dance, she wakes up in the body of Yun-ru the day before the accident and realises she can save Zi-wei if only she can convince him, and herself, that the danger is real.

Moving the action to 2014 does rather undermine the nostalgic power of the song along with that of the walkman itself as a kind symbol of a late ‘90s youth only hinted at in brief flashes of Zi-wei’s high school days that were most likely better fleshed out in the TV series. Then again the theme of nostalgia is itself destructive given that the opening lines remark on how “silly” it is to try to hold on to “something that is vanishing” which is what each of the lovers is trying to do in the time slip drama by attempting to prevent the accident at the building site (though it doesn’t seem to occur to any of them that they could just not go there).

As the rather trite closing quotation suggests it’s better to have lost and lost than not loved at all, each of the lovers realising that they cannot in fact change the past however much they might wish to and should try to do their best to enjoy the time they’ve been given with those they love for no one knows how long that will be. Nevertheless, there’s no denying that all the body swapping, multiverse shenanigans become incredibly convoluted, especially towards he film’s conclusion, making it largely impossible to keep track of who is who at the current time and what their relations to each other are. Viewers of the TV drama will be better placed to decipher whom some late introductions actually are given that their presence goes largely unexplained save for vague references to their names.

Then again, we can’t be sure if the heroine eventually wakes up from a dream or is unable to do so becoming trapped in a fantasy of lost love defined by dream logic and wilful nostalgia rather than the anxieties of her nightmare in which she feared that though Zi-wei held her tight he would one day disappear. Undoubtedly confusing, the film nevertheless manages to deliver its time slipping messages of the importance of holding every moment close and then treasuring the memories of lost love rather than continuing to pine for something that can never be regained.

Trailer (English subtitles)