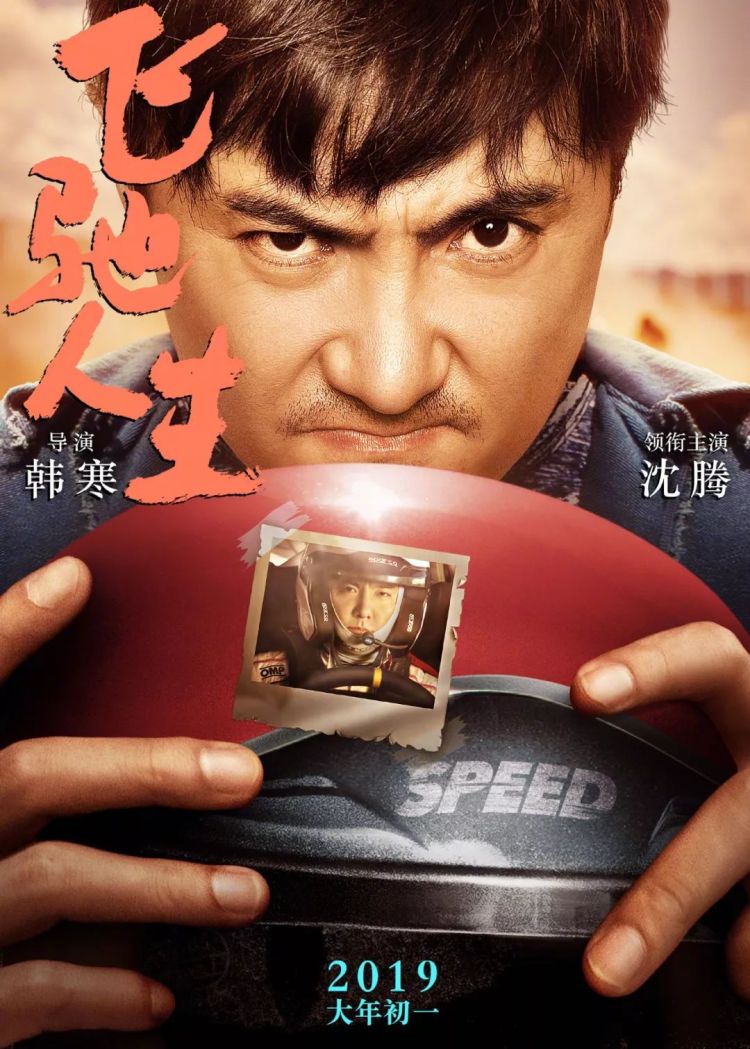

Traditionally speaking, New Year has often been a time for reconsidering one’s life choices, but can it ever really be too late to make up for past mistakes and charge ahead into a better future? The hero of Han Han’s New Year racing drama Pegasus (飞驰人生, Fēichí Rénshēng) is determined to find out as he tries to bounce back from disgrace and failure to prove to his young son that he was once a great man and not quite the hangdog loser he might at first seem. His battle, however, will be a tough one even with his best guys by his side.

Traditionally speaking, New Year has often been a time for reconsidering one’s life choices, but can it ever really be too late to make up for past mistakes and charge ahead into a better future? The hero of Han Han’s New Year racing drama Pegasus (飞驰人生, Fēichí Rénshēng) is determined to find out as he tries to bounce back from disgrace and failure to prove to his young son that he was once a great man and not quite the hangdog loser he might at first seem. His battle, however, will be a tough one even with his best guys by his side.

Zheng Chi (Shen Teng) dreamed of racing glory and won it. He was a champion, the face on billboards across China, but a minor scandal put paid to his success and his driving and racing licenses have been suspended for the last five years during which time he’s been humbled and lived a workaday life as a fried rice stall vendor raising a young son alone. Now that his suspension is up for reconsideration, he’s beginning to wonder if he might be able to return to his rightful place at the centre of the podium but he’ll have to eat a considerable amount of humble pie if he’s to convince anyone that he’s a person worthy of respect now that he has nothing.

Director Han Han is, among other things, also a rally driver himself though his positioning of the sport within his tale of middle-aged loserdom is a slightly awkward fit. Racing is an expensive hobby, it quite literally relies on the involvement of those who have vast resources of disposable cash they can use to sponsor drivers so they can improve their equipment. Though a driver’s skill, and their relationship with a co-driver, are not insignificant parts of the equation, it is nevertheless true that money rules all when it comes to buying advantage (perhaps much like life).

Chi’s problem isn’t just his age, but that he’s up against extremely rich young guys with inherited wealth like his rival Zhengdong (Huang Jingyu) – a pretty boy with celebrity following and seemingly infinite resources. Han sets Chi’s struggle up as one of the chastened everyman – someone who came from nothing and made it only to crash and burn but still has the desire to get up and try again. He struggles on through various obstacles including bribing a driving instructor to get his licence back and charming a suspension board into letting him back in the game but discovers that friendships formed when successful might not survive a fall from grace. He can’t get the same kind of access as he could when he was riding high and no amount of chutzpah will make up for the disadvantage incurred through not having the kind of wealth that enables Zhengdong’s ongoing rise to glory.

Nevertheless, perhaps Zhengdong is simply a realist when he advises those looking for absolute fairness not to bother getting involved with racing. He’s not a bad guy, if somewhat insecure in feeling as if his own success has been enabled only by Chi’s fall from grace and perhaps he wouldn’t be top of the podium if the best driver hadn’t been hounded off the track. What we’re left with is an awkward admission that what makes the difference is men like Zhengdong deciding to feel philanthropic, though in this case he does so out of a sense of sportsmanship and a not entirely altruistic desire to prove himself by ensuring the participation of a worthy rival. Given this boost, Chi’s quest necessarily leaves the realm of the everyday loser and returns to the rarefied one of success enabled by privilege.

The final messages are also somewhat ambivalent in their death or glory, live full throttle intensity as Chi’s lectures on driving become lectures about life, affirming that those who win are the ones who drive fastest while making the fewest mistakes. Chi is not unencumbered, he has his son and therefore a responsibility to another which is sometimes forgotten in his own quest for glory which, we are reminded, carries risk and danger. Perhaps what we’re asked is if the gentle pleasures of a simple life selling fried rice for decades are worth giving up the hyper acceleration of a life measured in seconds following a dream. Chi might have found his answer, but it comes at a cost and he’s not the only one who’ll be paying it. As New Year messages go, it’s a decidedly mixed one which might not offer much positivity for the average middle-aged loser longing to relive their glory days in service of a dream which might long have flickered out in an increasingly unequal society.

Currently on limited release in UK cinemas.

Original trailer (English subtitles)