Taro’s (Hiroki Sano) problem as far as he sees it, is that he lacks self-confidence and is unable to understand why other might like him, though he fears few do. That’s especially true of his girlfriend/financial backer Yuki (Saki Kato) about whom he makes a short documentary because he thought it would be good to make a film about the person who’s most important to him. But Yuki fires back that the person who’s most important to him is himself, so he should turn the camera around, but that’s exactly what he doesn’t want to do even if the film is really about himself anyway.

To that extent the film backfires in that, when he’s unexpectedly invited to a festival in Beppu and and convinced by Yuki to go because she’s irritated by just how little effort he seems to put in, all anyone can talk about is Yuki who they say must love him very much or at any rate has a lot of patience and understanding. This is doubly true of the lady running the Bluebird Theatre who says out loud live during the Q&A that his film was boring, and she only chose it because of the contrast between how mediocre the film was and Yuki’s force of personality. She suggests that Taro doesn’t know what sort of films he wants to make, or even why he’s making them in the first place, and she’s right.

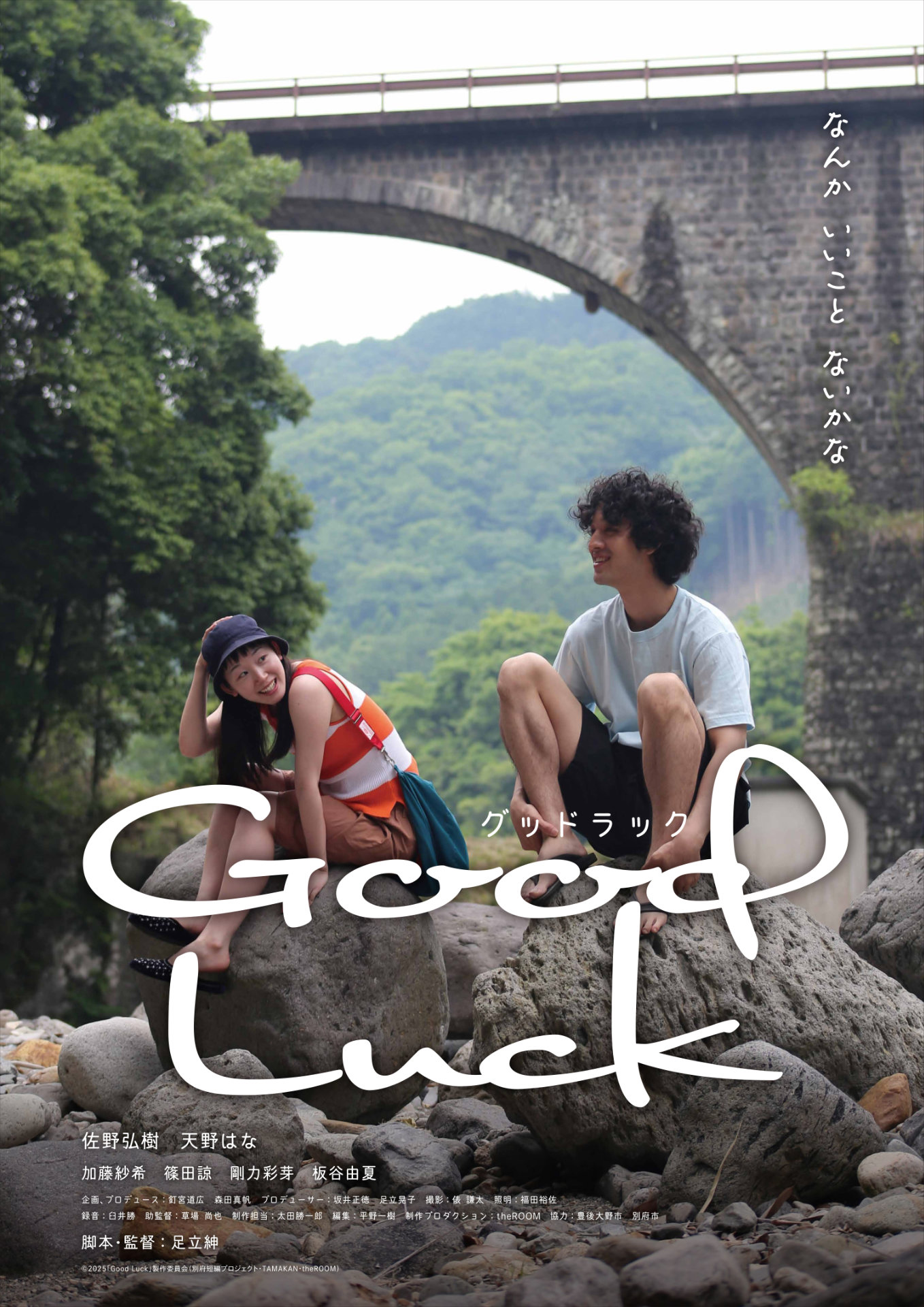

Awkwardly, this sense of confusion seems bound up with his relationship with Yuki which is unbalanced in his mind because she asked him out rather than the other way round. As he tells Miki (Hana Amano), an extremely extroverted young woman with an amazing laugh that he meets on his travels, his biggest regret in life is not being able to tell he girl he liked that he liked her in high school. This indecision and lack of confidence have left him directionless in his film career and uncertain in his relationships while it seems clear Yuki is not really his muse despite what others might say about her star quality if only by virtue of how sorry they feel for her for having to put up with Taro.

But then again, he’s basically swept away Miki too who hijacks his last couple of days touring the saunas around the hot springs resort. She explains that she likes to travel alone because she difficulties interacting with other people, though she gets along much better with strangers which is why she clicks so quickly with Taro even if he’s only hanging out with her by virtue of being too polite/spineless to decline her invitations. The pair end up echoing Before Sunrise in their walking tour of the natural attractions of the area, while Miki tells him that her biggest regret in life is that she hasn’t achieved anything that society values even if there are things that she’s good at and fears that she won’t be able to do the things that she wants to do before she dies.

Truth be told, Taro doesn’t really do much for Miki or ask any real followup questions while simultaneously beginning to fantasise about her as recounted through an incrediblely meta sequence taking place in his treehouse room. Nevertheless, he begins to see in her the kind of muse he’s been looking for along with discovering why he wants to make films and what kind of films he wants to make. But in then in true Adachi fashion, maybe Taro is just as superficial as he says he is and later drawn to another pretty woman on a train all while not making that much of an effort to get back to Yuki whose father has had a heart attack to which Taro seems mostly indifferent. There are certainly lots of strange women around Taro from the gloomy innkeeper in Beppo to the gaggle of ladies at a shrine convinced he’s an old high school friend, but as much as he has a talent for encountering the surreal, Taro doesn’t seem to know what to do with it and remains a somewhat passive observer to afraid to voice his feelings, simultaneously making films only about himself that nevertheless express nothing of his own soul.

Good Luck screened as part of this year’s Camera Japan.

Trailer (no subtitles)