Japan’s rapidly ageing society has provoked an epidemic of loneliness but also perhaps new business opportunities in Bunji Sotoyama’s empathetic social drama Tea Friends (茶飲友達, Chanomi Tomodachi). The phrase may sound innocuous enough, but given some potentially outdated cultural connotations the men who spot the advert cunningly placed in a newspaper to catch the eyes of older readers may have reason to assume that it’s more than just tea and chat on offer. Though as it turns out, it’s not just the old who are lonely as a younger generation in turn often in conflict with their parents also attempt to seek security and comfort in found family.

That said, there’s something a little cult-like about the way that Mana (Rei Okamoto), a former sex worker, talks about her organisation which aims to cure late life loneliness through what others might describe as an elderly sex ring. Employing a collection of older women, she accompanies them to meet new clients where they silently slide viagra over the table. The gentleman caller subscribes to a plan to purchase “tea” and anything that happens inside the hotel room they subsequently go to is just “free love” rather than “prostitution”. Mana sees herself as running a “community safety net” and helping elderly people who might otherwise have become isolated and depressed keep active as part of one big happy family along with the other members of staff who have, like her, become estranged from their parents and relatives.

For Yoshiki, one of the men who escorts the ladies around, it’s that he views his father as a failure for leaving a well-paid corporate job to open a bakery which subsequently went bankrupt and has led to him living in his car. He thinks that in the end it’s better not to try at all than be left with the humiliation of things not working out. But then for Mana herself it’s more a sense of parental rejection. After a difficult childhood, her now terminally ill mother continues to reject her on the grounds of her history of sex work while she continues to crave the unconditional love of a family. Like a mother hen, she nestles those around her into the Tea Friends organisation which operates out of her own home and strives to create a place where everyone can feel they belong.

Which is all to say she’s the loneliest one of all, but as someone else later cautions her you can’t cure your own loneliness with the loneliness of others. What she sees as a social enterprise others may see as a deliberate attempt to take advantage of vulnerable people who have admittedly been let down by an indifferent society and are in need of the money even more so than comfort or validation. At the other end of the spectrum, a young woman working at Tea Friends discovers that she is pregnant but her boyfriend immediately rejects her, insisting that he refuses to take responsibility and revealing that he is already married. Chika wants to have her baby, but everyone seems to be telling her that she shouldn’t. The doctors seem to look down on her after realising she isn’t married and the father most likely not in the picture, while an attempt to inquire about benefits at the town hall leads only to judgement as the clerk pithily tells her that they’re there for when you need them but she shouldn’t “depend” on them too much virtually calling her a scrounger and implying she’s been irresponsible in becoming a single mother.

As another of the older women admits, being used was better than being ignored and at least being part of Tea Friends gave her a sense of purpose and acceptance if only for a time. In any case, Mana’s attempt to find unconditional love from her new “family” largely flounders as even those she’d come to believe herself close to desert her when the threat of legal proceedings enters the picture leaving her to face the music alone while she continues to protect them insisting that they’ve done nothing wrong even if it it was technically against the law. An old man’s devastation on picking up the phone and getting no answer suggests that Mana might have had a point when she said it was a social service seeing as no one else seems keen to tackle the problem of late life loneliness even if she did go about it in a problematic way. As Mana often says, righteousness does not equal happiness and it is often outdated social brainwashing that keeps people unhappy and not least herself as she struggles to find the unconditional love lacking in her life that would enable her to cure her own loneliness even in the prime of her youth.

Tea Friends screened as part of this year’s Camera Japan.

Original trailer (English subtitles)

The three films loosely banded together under the retrospectively applied title of the Black Society Trilogy are not connected in terms of narrative, characters, tone, or location but they do all reflect on attitudes to foreignness, both of a national and of a spiritual kind. Like Tatsuhito in the first film,

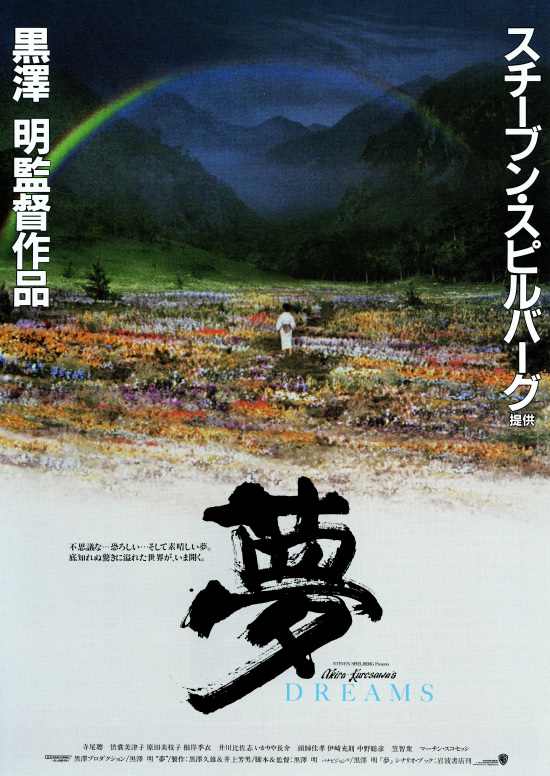

The three films loosely banded together under the retrospectively applied title of the Black Society Trilogy are not connected in terms of narrative, characters, tone, or location but they do all reflect on attitudes to foreignness, both of a national and of a spiritual kind. Like Tatsuhito in the first film,  Despite a long and hugely successful career which saw him feted as the man who’d put Japanese cinema on the international map, Akira Kurosawa’s fortunes took a tumble in the late ‘60s with an ill fated attempt to break into Hollywood. Tora! Tora! Tora! was to be a landmark film collaboration detailing the attack on Pearl Harbour from both the American and Japanese sides with Kurosawa directing the Japanese half, and an American director handling the English language content. However, the American director was not someone the prestigious caliber of David Lean as Kurosawa had hoped and his script was constantly picked apart and reduced.

Despite a long and hugely successful career which saw him feted as the man who’d put Japanese cinema on the international map, Akira Kurosawa’s fortunes took a tumble in the late ‘60s with an ill fated attempt to break into Hollywood. Tora! Tora! Tora! was to be a landmark film collaboration detailing the attack on Pearl Harbour from both the American and Japanese sides with Kurosawa directing the Japanese half, and an American director handling the English language content. However, the American director was not someone the prestigious caliber of David Lean as Kurosawa had hoped and his script was constantly picked apart and reduced. Review of Takeshi Kitano’s A Scene at the Sea – first published by

Review of Takeshi Kitano’s A Scene at the Sea – first published by