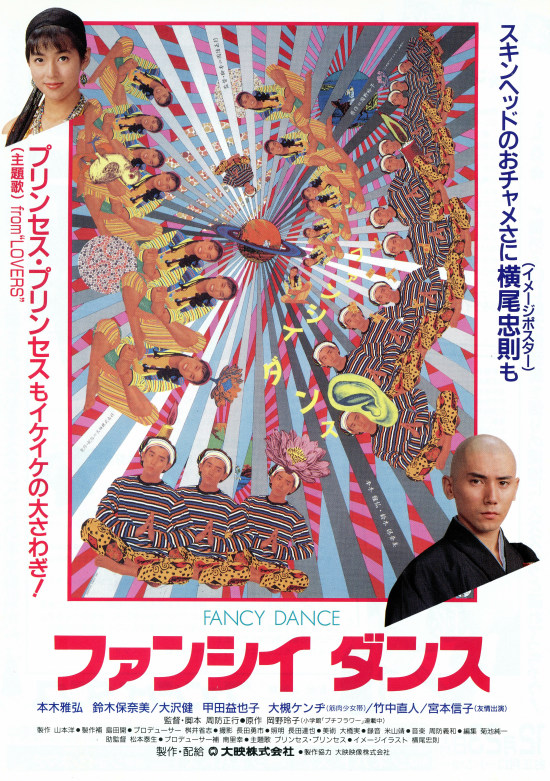

Thematically speaking, the films of Masayuki Suo have two main focuses either dealing with esoteric ways of life in contemporary Japan such as sumo wrestling in Sumo Do Sumo Don’t, ballroom dancing in Shall We Dance?, and geisha in Lady Maiko, or pressing social issues such the operation of the justice system in I Just Didn’t Do It or euthanasia in A Terminal Trust. After making his debut with pink film Abnormal Family: Older Brother’s Bride, Suo’s first mainstream feature Fancy Dance (ファンシイダンス) belongs to the former category as a Bubble-era punk rocker finds himself entering a temple to honour a familial legacy.

As the film opens, Yohei (Masahiro Motoki) is onstage singing a very polite and respectable version of a classic song, Wakamonotachi (lit. the young), made popular as the theme to a television drama in the mid-1960s, before suddenly turning around, the other half of his head already shaved continuing with the same song but now in an anarchic punk rock arrangement. The son of Buddhist temple, he is expected to become a monk and take over the family business but he’s also a young man coming of age in the ultra-materialist Bubble era raised in the city and with little inclination towards the ideals of Zen. In fact, we learn he’d long resisted the idea of entering a monastery and has only recently given in intending to stick it out for a year in order to please his parents and then return to to his Tokyo life.

His hair reflects an inner duality, torn between his duty to take up Zen and his desire for personal freedom. Yet as he’s repeatedly told by his razor-wielding office lady girlfriend Masoho (Honami Suzuki), in the end he’s going to have to choose which from her point of view means choosing between her and the temple. Though there is obviously no prohibition on monks getting married, Yohei is the son of a monk after all, girlfriends are one of many things not really allowed during his initiatory period though as we’ll see the monastic life is often more about knowing how to game the system than it is about actually sticking to the rules. It’s a minor irony that temples, Buddhist or Shinto, are actually one of the most lucrative businesses in Japanese society and despite apparently rejecting material desire many monks are fantastically wealthy. Yohei’s fellow noviciate Eishun (Hikomaro) is dropped off by a young woman in a bright red sports car who turns out to be the daughter of a monk, Eishun only entering the temple to please her family so that he can marry her, committing himself out of love but also admitting it’s nice work if you can get it.

Yohei’s brother Ikuo (Ken Ohsawa) is also fine with the idea of becoming a monk, describing it perhaps surprisingly as an “easy life”. Ikuo’s presence is initially a little irritating to Yohei, he only agreed because he was under the impression Ikuo had also declined to enter the temple and feels that he’s been tricked when he could have just let him train to take over the family “business”. The treatment they receive is often surprisingly harsh with a high level of physical violence administered by their superiors, in particular the more experienced Koki (Naoto Takenaka) who has it seems figured out how to break the rules in an acceptable fashion carrying on a secret romance with a young woman who often attends the temple while visiting hostess bars in the town in disguise, wearing a wig to cover his distinctive monastic hairstyle. Meanwhile, even the supposedly austere master of asceticism Shoei (Miyako Koda) has a secret stash of sweets in their room. The message seems to be that once you “graduate” from the junior ranks you too are free to interpret the tenets of a Zen life however you see fit.

Yet despite himself, Yohei comes to appreciate the trappings of monasticism most particularly in its graceful movements and the aesthetic quality of the outfits. The temple may not be free of the consumerist corruptions of the Bubble era, but perhaps there is something it for a man like Yohei, a different kind of “freedom” than he’d envisioned but freedom all the same even within the constraints of a superficial asceticism. Masoho meanwhile rejects her own fancy dance in refusing to play the part of the conventional office lady no longer smiling sweetly cute and invisible but dressing in her own individual style and defiantly taking command of the room. The strains of Wakamonotachi recur throughout hinting at Yohei’s youthful confusion as he tries to decide on his path in or out of the temple while finding himself “swimming in a sea of desire between Masoho and Zen”, perhaps concluding that his own endless journey has only just begun.

Fancy Dance streams in the US Dec. 3 to 23 alongside Suo’s 2019 Taisho-era drama Talking the Pictures as part of Japan Society New York’s Flash Forward series.

Wakamonotachi TV drama theme by The Broadside Four (1966)

Music video for the updated theme from the 2014 TV drama remake (known as All About My Siblings) performed by Naotaro Moriyama