An ambitious executive is confronted with the emasculating nature of the salaryman dream when escaped convicts invade his home in an early thriller from Kinji Fukasaku, The Threat (脅迫, Odoshi). The threat in this case is to his family and implicitly his manhood in his ability or otherwise to protect them while accepting that his aspirational life has come at the expense of his integrity and left him, ironically, hostage to the whims of his superiors.

This much is obvious from the opening sequence which takes place at a wedding where Misawa (Rentaro Mikuni) is giving a speech congratulating two employees on their marriage. Misawa’s speech is long and boring, as such speeches tend to be, and according to some of the other guests disingenuous in giving glowing reports of two ordinary office workers while skirting around the elephant in the room which is that Misawa has played matchmaker to convince an ambitious junior to marry his boss’ mistress for appearance’s sake. As Misawa himself has done, the employee has sacrificed a vision of masculinity for professional gain in accepting that his wife’s body will “belong” to another man and it is the boss who will continue sleeping with her.

The only person not aware what’s going on is Misawa’s naive wife, Hiroko (Masumi Harukawa), who enjoyed the wedding and remarked that the couple seemed very well suited giving rise to an ironic laugh from Misawa who of course knows that not to be the case. They return by car to a nice-looking home but one that stands alone at the end of a street preceded by a series of vacant lots presumably available to other similarly aspirant salarymen yet to make a purchase. Shortly after they arrive, two men force their way in and insist on staying explaining that they are the pair of escaped death row convicts that have been in the papers and are in fact in the middle of a kidnapping having taken the grandson of a prominent doctor with the intention of using the ransom money to illicitly board a ship and leave the country.

Naked and covered in soap suds having been caught in the bath, Misawa is fairly powerless to resist and can only hope to appease the men hoping they will leave when their business is done. His acquiescence lowers his estimation in the eyes of his young son, Masao (Pepe Hozumi), who later calls him a coward and is forever doing things to annoy the kidnappers such as attempting to raise the alarm with visitors by smashing a glass or speaking out against them while Misawa vacillates between going along with the kidnapper’s demands or defying them to contact the police. After failing to retrieve the money when ordered to act as the bag man, Misawa stays out trying to find another way to get the cash and Masao wonders if he’ll come back or will in fact abandon them and seek safety on his own. Misawa really is tempted, darting onto a train out of the city his eyes flitting between the sorry scene of a small boy with a tearstained face tugging the sleeves of his father who seems to have fallen down drunk on the station steps, and a woman across from him breastfeeding an infant. He gets off the train only at the last minute as it begins to leave the station as if suddenly remembering his role as a father and a husband and deciding to make a stand to reclaim his patriarchal masculinity.

The brainier of the kidnappers, Kawanishi (Ko Nishimura), had described Misawa as a like robot, idly playing with Masao’s scalextrics insisting that he could only follow the path they were laying down for him much as he’d already been railroaded by the salaryman dream. During a car ride Kawanishi had asked Misawa what he’d done in the war. Misawa replied that he was in the army, but had not killed anyone. Kawanishi jokes that he’d probably never raped a woman either, but to that Misawa gives no answer. Realising that the other kidnapper, Sabu (Hideo Murota), had tried to rape Hiroko he turns his anger towards her rather than the kidnappers striking her across the face and later raping her himself avenging his wounded masculinity on the body his of wife while unable to stand up to either of the other men.

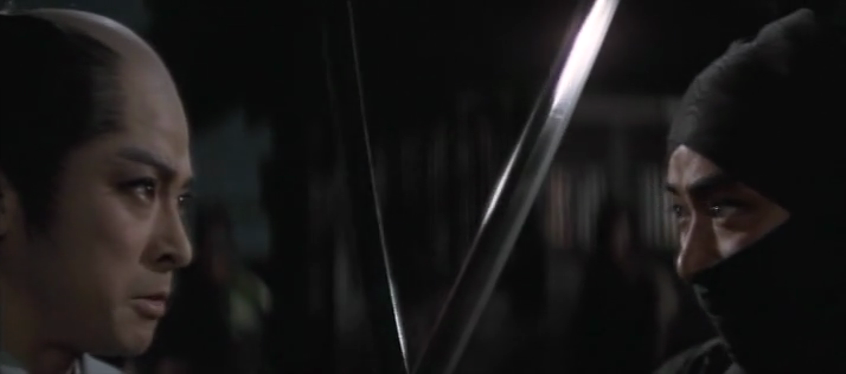

Kawanishi giggles and describes him as exactly the kind of man he assumed him to be but he’s both wrong and right. Misawa had been spineless, insecure in the masculinity he largely defined through corporate success though as Kawanishi points out most of what’s in the house is likely being paid for in instalments meaning that technically none of it’s actually his. He defined his position as a father as that of a provider, ensuring a comfortable life his wife and son rather than placing importance on his ability to protect them physically from the more rarefied threats of the contemporary society such as crime and violence. On leaving the train, another symbol of the path laid down for him both by the salaryman existence and by Kawanishi, he is able to reclaim a more primal side of his manhood in formulating a plan of resistance to lure the kidnappers away from his wife and son.

But then in another sense, it’s Hiroko who is the most defiant often telling the kidnappers exactly what she thinks of them while taking care of the kidnapped baby and doing what she can to mitigate this awful and impossible situation in light of her husband’s ineffectuality and possible disregard. She is the one who finally tells Kawanishi that she no longer cares if he kills her but she refuses bow to his authority and he no longer has any control over her. Even so, the film’s conclusion is founded on Misawa’s reacceptance of his paternity in a literal embrace of his son, redefining his vision of masculinity as seen through the prism of that he wishes to convey to Masao as an image of proper manhood. Fukasaku sets Misawa adrift in a confusing city lit by corporatising neon in which the spectre of the Mitsubishi building seems to haunt him amid the urgent montage and tilting angles of the director’s signature style still in the process of refinement as Misawa contemplates how to negotiate the return of his own kidnapped family from the clutches of a consumerist society.