When a passenger plane is hijacked and forced to fly to North Korea in 1969, the Korean Air Force pilot ordered to fire on it refuses. He recognises the pilot and realises there is something wrong. If there is a hijacker on board, he fears that that he may kill the pilot and crash the plane, killing everyone on board, and while his commanders remind him that the plane should be able to land on just one engine, he knows that if he hits the fuselage instead, the plane could blow up. Even if they land in North Korea, isn’t it better everyone survives?

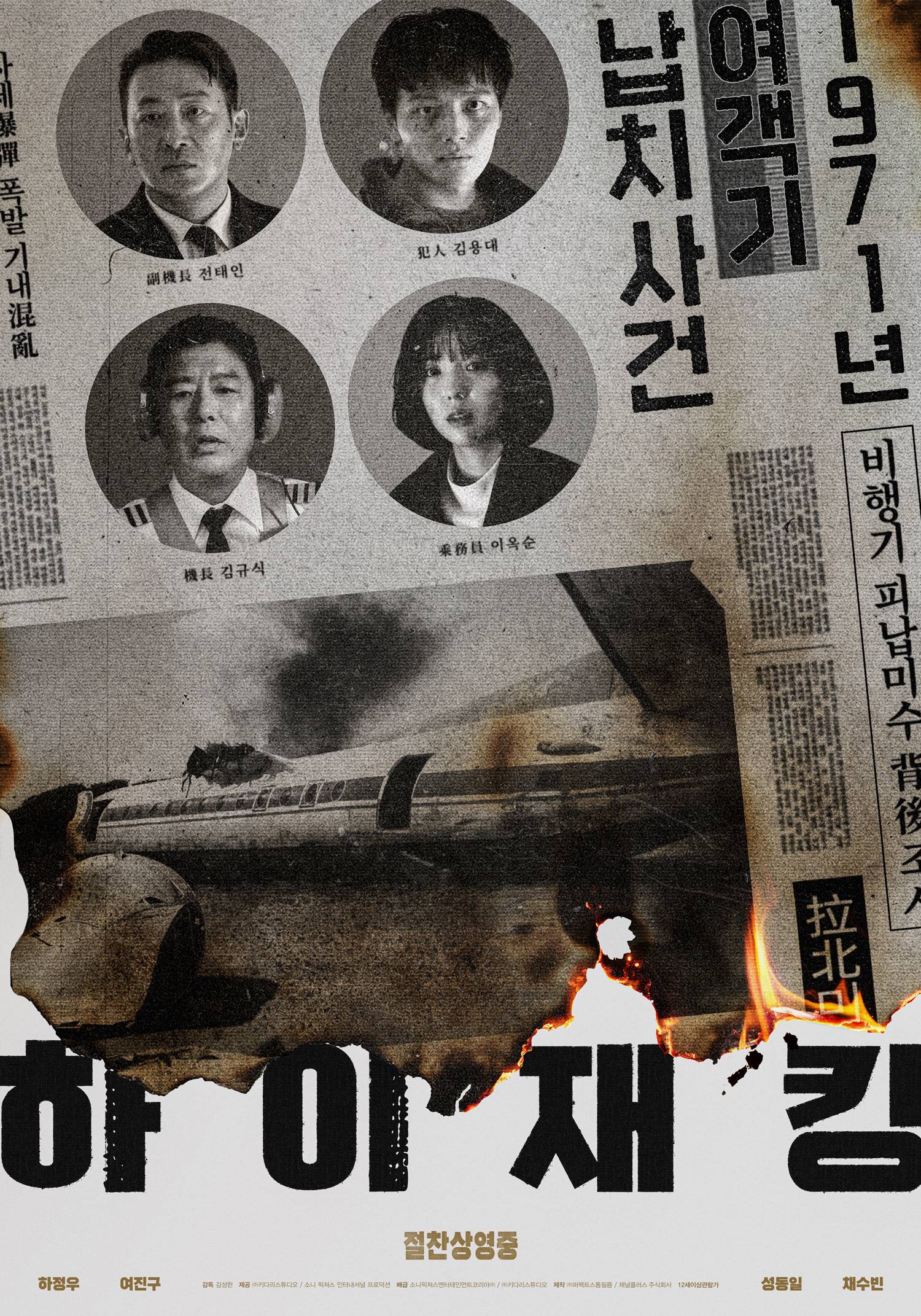

Not according to some in Kim Sung-han’s Hijack, 1971 (하이재킹, Hijacking), inspired by a real life incident. Tae-in (Ha Jung-woo) is summarily dismissed from the air force for his insubordination while otherwise ostracised as the man who allowed the plane to reach North Korea. As he predicted, most of the passengers are returned home shortly afterwards, but 11 never see the South again including his friend the pilot, Min-su (Choi Kwang-il). Meanwhile, Min-su’s wife (Kim Sun-young) continues to face harassment for supposedly being a communist sympathiser. Now working for a commercial airliner, Tae-in also faces discrimination from his new colleagues who, ironically, don’t trust him to properly protect passengers. All their assumptions are tested, however, when a young man sneaks a bomb on board and threatens them to fly to the North apparently inspired by the previous case in which the hijacker was given a hero’s welcome for successfully kidnapping so many useful people.

What’s immediately obvious is how easy it still was to get a bomb on a plane. Yong-dae (Yeo Jin-goo) simply packs them into some tin cans and wraps them up like a picnic. When boarding opens, the passengers literally sprint past each other to get the best seats because they weren’t yet reserved, and when we see a passenger start smoking, we assume the stewardess will tell him not to yet she simply points out the ash tray in the arm of the seat and asks him not to drop ash on the floor or woman sitting next to him. One woman also delays the flight because she’s brought a live chicken with her to make a soup for her daughter whom she’s travelling to see because she’s ill. Tae-in scores an early win and the goodwill of (most of) the passengers by defusing the chicken situation and allowing the woman to keep it on the condition she has it on her lap for the duration of the flight.

Letting the old lady keep the chicken signals Tae-in’s consideration for his passengers’ welfare and happiness, while the air marshal becomes so preoccupied with this minor breach of the rules that he fails to notice the suspicious behaviour of the hijacker. The presence of the air marshal, a precaution taken after the previous incident, also proves counterproductive when he’s injured when the first bomb goes off, allowing Yong-dae to steal his gun. Granted, this is a fairly minor flight from a provincial airport to Seoul so maybe no one really thought there was much need for advanced security, but they really are woefully underprepared for this kind of incident, especially after the pilot is seriously injured and can’t see well enough to fly alone, meaning Tae-in also cannot do very much to respond to the hijacker’s threats.

But what we come to realise is that it’s really society that’s been hijacked by the extreme prejudice directed towards “communists” and the North. The passengers from the first plane were returned, but spent time in interrogation to make sure they hadn’t been turned. A newlywed passenger also remarks that a fisherman friend of his was abducted and the police haven’t stopped hassling him about being a spy ever since he got back. Yeong-do’s motive is that he faced constant and unwarranted harassment, including being scalded with boiling water as a child, because his older brother defected to North Korea. His mother later died when he was carted off to prison for being a supposed sympathiser, while other passengers on the plane are similarly worried that their families will starve if they end up in North Korea or are detained when they return.

A minor subplot, meanwhile, explores the prejudice faced by an older woman travelling to Seoul with her son, who has become a prosecutor. She is deaf and unable to speak, but her son tells her to stop signing because it’s embarrassing him after noticing disapproving looks from another woman in hanbok across the aisle. The old lady had also taken her shoes off after getting on the plane as if she were entering someone else’s home signalling both her politeness and lack of familiarity with modern customs. Her son had repeated the stewardess’ instructions to put them back on, but addresses her like stranger when telling her not to sign. In a way, this casual prejudice is the same and directed at someone simply for being different. Even so, there’s something quite tragic about her son being ordered to tear up the prosecutor ID card she was so proud of. Eventually she swallows it herself to make sure no trace of it remains, telling her son not to worry she will always protect him even in North Korea though he has not done very much to protect her here.

Tae-in later does something similar when he encourages Yong-dae that they should all go on living to ensure no one else endures the mistreatment he has and we don’t end up with any more incidents like this. Though his behaviour is increasingly deranged, it becomes easy to sympathise with Yong-dae for enduring so much suffering for something that was really nothing to do with him while we’re constantly reminded that if the plane lands in North Korea everyone on the plane and all their relatives will also suffer the same fate. At least facing this disaster together eventually forces the passengers to set aside their petty prejudices and pitch in to save the plane so they can get home to their families even if it’ll take them a bit longer to get to Seoul. Though the outcome is already known to the home audience, Kim Sung-han keeps the tension high and defines heroism largely as compassion and selflessness in Tae-in’s continued efforts to ensure the safety of his passengers rather than playing politics or allowing himself to be swayed by those who think landing in North Korea is a fate worse than death.

International trailer (English subtitles)