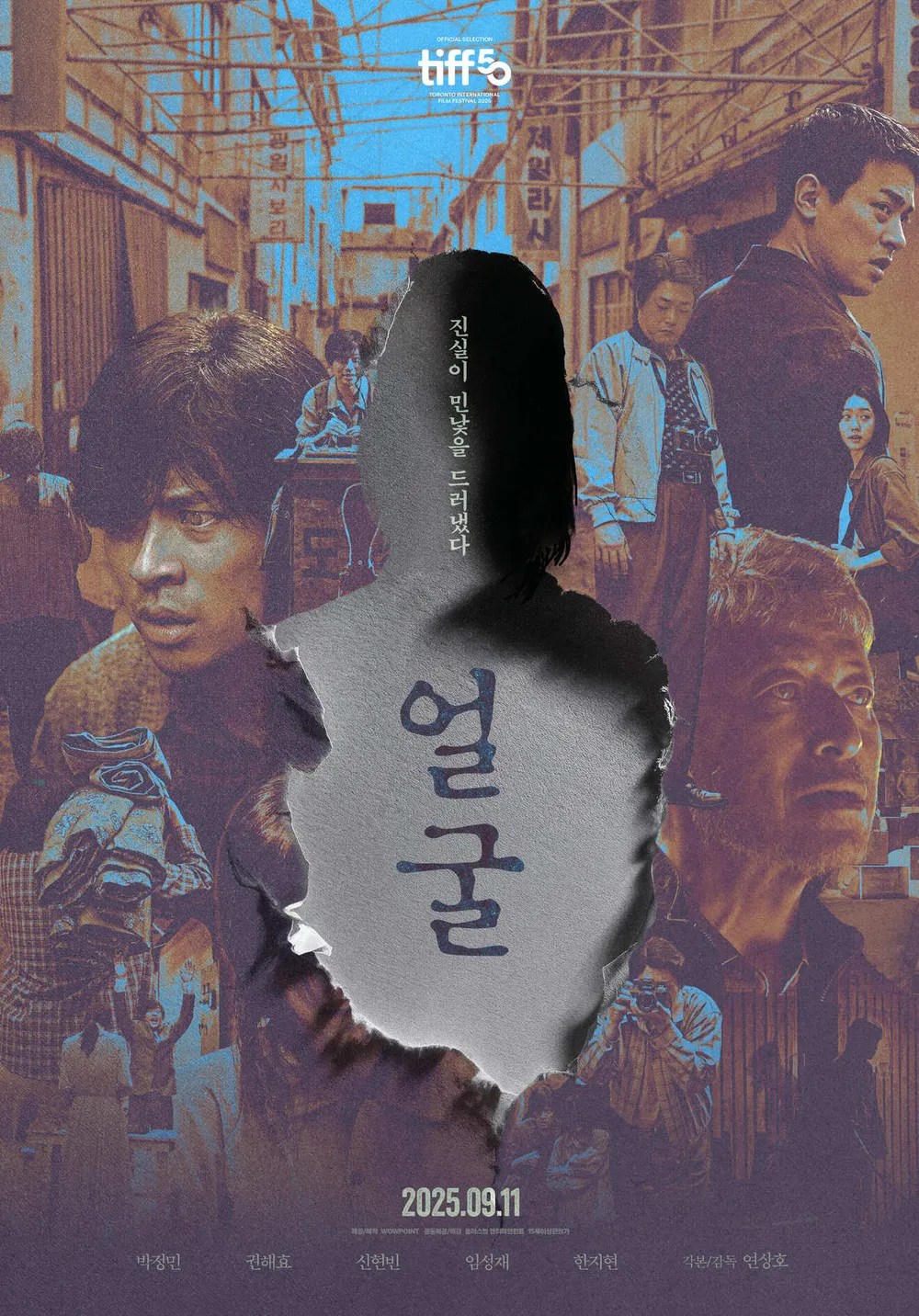

Poets and philosophers have long debated the true nature of “beauty”. “Living miracle of Korea” Yeong-gyu (Kwon Hae-hyo) has spent most of his life pondering it, not least because he is blind and is often told that the figures he carves on name stamps are “beautiful”. For his customers, “beauty” is rooted in the visual, and for those reasons it seems to them impossible for Yeong-gyu to experience it. It doesn’t occur to them that he may experience “beauty” in other ways or that beauty is not necessarily as connected with vision as they assume it to be.

But then again, in Yeon Sang-ho’s dark fairytale The Ugly (얼굴, Eolgul), the concept of “beauty” is itself inverted to become something eerie and uncomfortable in symbolising the forced harmony of an authoritarian society. In the present day, a TV documentary crew is interviewing blind stamp carver Yeon-gyu, though it’s obvious the producer is becoming frustrated with Yeong-gyu’s evasiveness while simultaneously hoping to tell an inspirational story about how he overcame adversity that is in itself a little exploitative. She gets an ironic lucky break when, midway through filming, the remains of Yeong-gyu’s wife and the mother of his only son Dong-hwan (Park Jeong-min) are discovered following her disappearance 40 years previously.

Yeong-gyu had told Dong-hwan, who was a baby at the time, that Young-hee had simply run away and does not seem to have made much attempt to look for her. Though this might seem odd, it was after all a time when people just disappeared without warning and asking questions would only put those left behind in danger, so perhaps it’s understandable that Yeong-gyu, a man marginalised by his disability, simply accepted the fact of her absence and chose to believe that she had left him even if it conflicts with his description of her as “kind”. Everyone describes Young-hee of having been a “kind” person even while they otherwise scorn her as “ugly”, describing her as a monstrous creature with an appearance they find gruesome though almost comical rather than frightening.

When Young-hee’s estranged family turn up at the funeral, they too are embarrassed by her ugliness and crassly make a point of clarifying to Dong-hwan that they don’t want to share their inheritance with him. According to them, Young-hee left home as a young child after telling their mother she’d seen their father with another woman. Their mother beat and her and refused to believe it, while the other family members resented Young-hee for raising an inconvenient truth and fracturing the harmony of this “perfect” family. Young-hee encounters something similar while working at clothing factory where she challenges the boss after finding out that he has raped an employee, but is again ignored and then silenced. Years later in the present day, the former workers claim that it’s thanks to the boss that they survived, echoing the defenders of dictator Park Chung-hee who credit him with curing the intense poverty of the post-Korean War society and turning the nation into the economic powerhouse it is today no matter how many died in his pet construction projects such as the Gyeongbu Expressway.

Young-hee too works under these exploitative conditions similar to those seen in A Single Spark. When her boss refuses her a bathroom break, she is too frightened to defy him and ends up soiling herself earning herself the unpleasant nickname “Dung Ogre”. Yet when she sees injustice she tries to combat it and refuses to back down even when others shun her. Gradually we begin to realise that the reason Young-hee is called “ugly” is because she speaks the truth and reflects the “ugliness” of those around her. Years later, the colleague who told her she’d been raped by the boss blames herself for her death, knowing that Young-hee was only trying to help her and probably didn’t realise that exposing the boss would kill her only resultiing in a quest to identify the victim. “My shame became his forgiveness,” she reflects, regretting that she too scorned Young-hee and that her failure to speak enabled him to go on abusing other women with impunity. Afraid of the factory boss’ violent thugs and desperate to keep their jobs, no one challenges him least of all Yeong-gyu who tells his wife to shut up and keep the peace.

But for Yeong-gyu, Young-hee’s “ugliness” has other implications in that it reflects his own insecurities and marginalisation. Along with using various derogatory terms to describe Young-hee’s ugliness, the interviews throw in a series of ableist slurs and it’s clear that they also consider Yeong-gyu to be “ugly” because of his otherness. Yeong-gyu resents that they look down him, and learning that Yeong-hee is considered to be “ugly” is consumed with a deep sense of humiliation as if he were being mocked and laughed at for having such an “ugly” wife while, paradocxically, she must only have been interested in him as a means of bringing about his degredation.

But then, this visual notion of “beauty” is meangingless to Yeong-gyu who has been blind since birth so it ought not to matter to him whether Young-hee is objectively beautiful to the sighted. Notions of visual beauty are socially and culturally defined and shift over time, but at this time and in this society being “beautiful” is it seems important, not least because it implies conformity. Young-hee’s “ugliness” is then transgressive and empowering in its defiance of the code of silence that defines authoritarianism, but within it Yeong-gyu finds only the undermining of his masculinity and humiliation in being found unworthy. That he’s now called a “living miracle of Korea” for overcoming those hard times is a cruel irony and a comment on the state of the contemporary nation forged in dictatorship and tempered by a hyper-capitalistic disregard for human rights in the quest for prosperity. Confronted by these truths, Dong-hwan finds himself with a choice, but in the end may take after his father after all in his own desire to tidy away unpleasantness and avoid having to accept the “ugly” reality.

The Ugly screened as part of this year’s LEAFF.

Trailer (English subtitles)