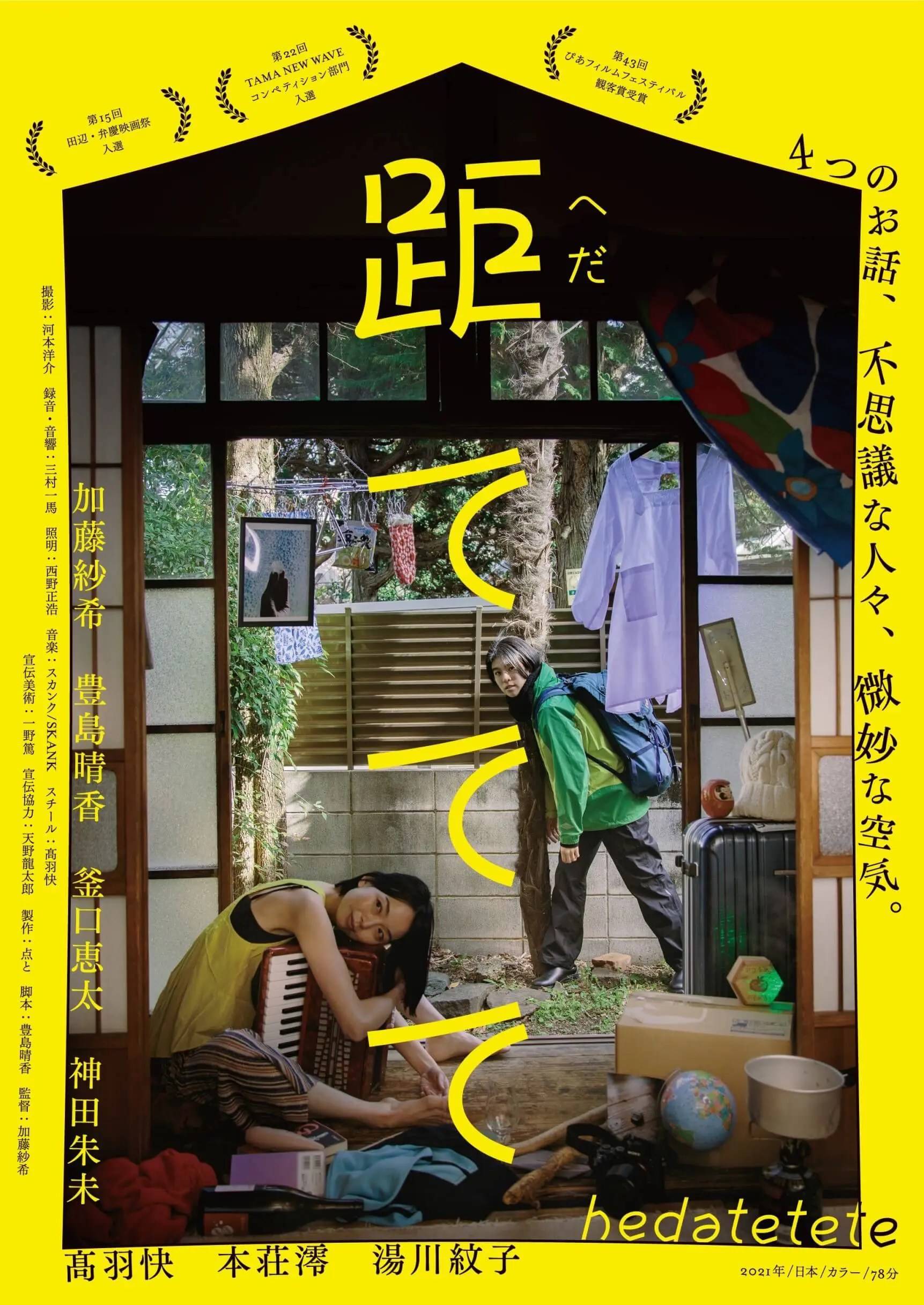

Can two people who have completely different outlooks and ways of living learn to get along and eventually become friends? A pandemic-era dramedy, Saki Kato’s In the Distance (距ててて, Hedatetete) asks just this question when two women are unexpectedly forced to co-exist on a greater level after their roommate is suddenly stuck abroad. A series of surreal adventures might leave them with no option other than to confront their differences, but also shows them that difference can be complementary rather than disharmonious.

The main issues between Ako and San are those which are common to any house sharing arrangement particularly if the people involved did know each other well previously. Ako is an aspiring photographer who sees part-time work as a necessary evil but continues to struggle amid the vagaries of the covid-era economy. She is neat and tidy and likes the house to be in order. San, meanwhile, is picking up most of the rent and has a job which has not been too badly affected by the pandemic. But she’s also a total mess when it comes to her share of the housework and has an annoying habit of picking up everyone’s post and stuffing it somewhere in her room without letting her roommates know a letter has come for them. Obviously, this is also an invasion of privacy on top of simply being annoying so Ako’s irritation is understandable but she has a kind of animosity towards San simply for being what she sees as a boring wage slave while she’s just slumming it until she gets a break with her photography.

But then again, San is “artistic” if in a problematic way in that her accordion playing has caused complaints from neighbours but when their property manager comes to have a word with them he ends up bringing his ocarina to join in the fun. San vents her frustrations to a friend, Tomoe, who has a similar problem of her own in that she’s in the process of breaking up with her boyfriend because they keep disagreeing over trivial things like brands of rice or misaligned printing on greetings cards. They only talk to each other in terms of metaphor with Tomoe apparently sick of their mismatched pairing and hoping to find a new partner with more common interests while the boyfriend seems near distraught by the thought of the relationship ending.

Ironically it’s San who points out their relationship may be fairly complementary and it’s more the case that they can get along together because they are different yet she still struggles with her relationship with Ako whom she finds uptight and pretentious. Ako, meanwhile, is having a strange encounter of her own with a teenage girl looking for a misdirected letter presumably spirited away by San. She claims not to have a phone or use a computer and implies that her mother is very strict, though when she actually arrives at the house she’s incredibly nice and even cooks a hearty meal though there is something a little sinister in her manner lending the pair a kind of supernatural quality like something out of a fairytale.

In any case, a misplaced keepsake eventually prompts a confrontation between the two women that allows them to clear the air and find a way to work together. Turning somewhat surreal in its final section, the film hints at a transportational quality of their new alliance that drops them in a new and unfamiliar place with only each other to rely on. The lesson seems to be that sharing an environment necessarily gives rise to various interpersonal issues which can be dissolved while outside of it, and that even if two people seem completely incompatible they can still find common ground and learn to get along especially against the stressful backdrop of a global pandemic in which enforced isolation can exert additional pressure on an already strained relationship just when mutual cooperation becomes an absolute necessity. Filmed with everyday naturalism and a surrealist, deadpan humour Kato’s indie dramedy hints at the strangeness of the ordinary but also discovers the small moments of unexpected connection often brokered by casual misunderstanding.

Original trailer (no subtitles)