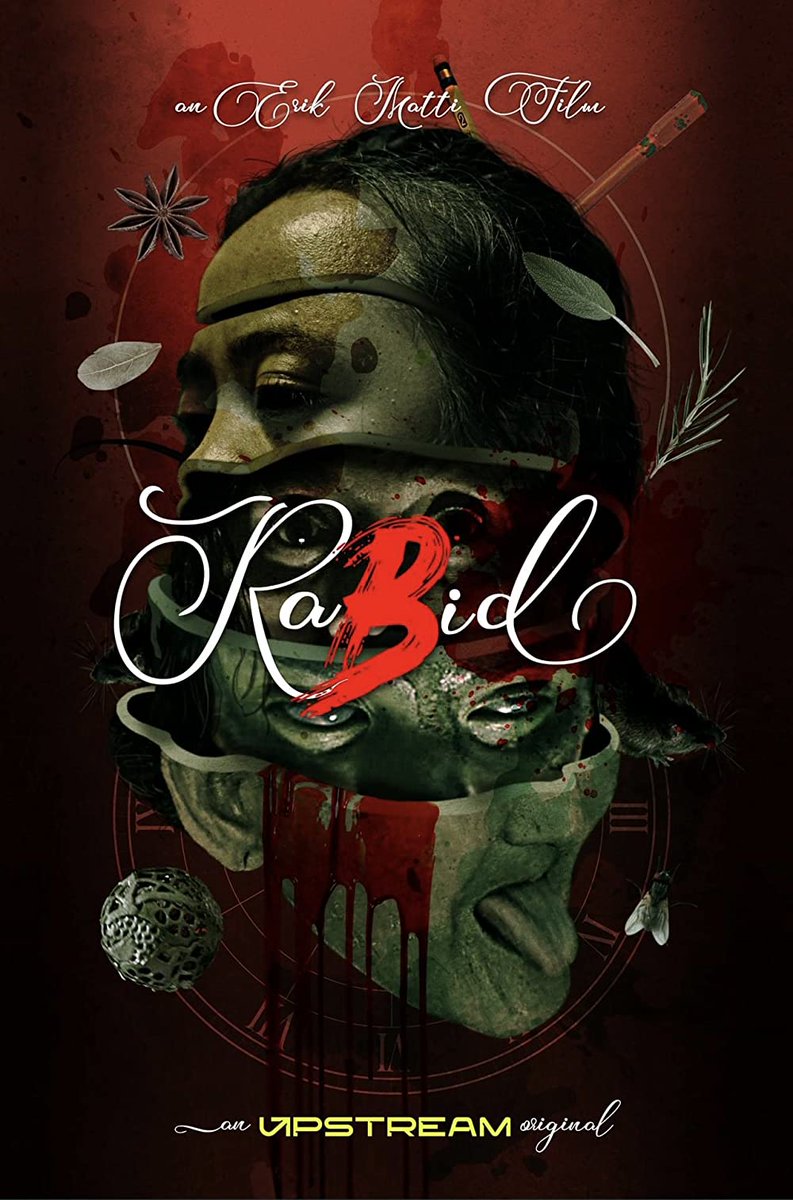

The last few years have obviously been stressful for everyone, but Erik Matti’s four-part pandemic-era horror anthology Rabid roots itself in the anxieties lurking below the simple fear of disease or strain of isolation painting a sometimes uncomfortable picture of the contemporary society. Ranging from class conflict to caring for the sick, brain drain, and economic despair, the four episodes find each of their protagonists trapped in a maddening world which no longer makes sense with little idea how they got there or how to escape.

The first chapter, “Bad Luck is a Bitch”, for instance takes place entirely within the home of a wealthy family whose lives have not changed drastically under coronavirus restrictions because their jobs can be done from home and their livelihoods do not depend on the kind of business that requires face to face interaction. The trouble starts when mother Mayette (Cheska Diaz) takes pity on an old woman who comes begging at her door with a sign stating she is a deaf mute whose son passed away of COVID-19. Mayette invites her to stay in the family’s home as an act of kindness but also one that’s tinged with snobbery explaining to her husband they can do with more help seeing as their maid is no longer available. The old woman is later exposed as a witch using black magic to possess the family and take over the house.

Her transformation could be red either as the family’s animosity towards the poor, the husband and daughter against taking the old woman in in case she has COVID-19, or as a manifestation of the poor’s resentment taking revenge on the rich for their lack of compassion. In any case it’s ironic that Mayette’s act of kindness has such devastating consequences for her family, the act itself corrected in the conclusion when she calls her daughter to help another beggar offering only food and sending the woman and her child on their way. Meanwhile the family’s attempt to get help from outside is frustrated by a breakdown of community trust during the pandemic when challenged by local patrols who remain suspicious of them and their health status, while the family’s modernity also undermines their safety their salvation coming only from the daughter’s boyfriend and his interest in the occult.

Chapter two’s “Nothing Beats Meat” by contrast is melancholy black and white treatment of love and isolation seemingly set in the midst of a zombie apocalypse in which a loving husband attempts to help his zombified wife beat her meat addiction by going cold turkey underground. Filled with a sense of fatalistic romance, the segment’s ironically upbeat ending asks what point there is in being well in a world of sickness when all the love and care there is will not bring the husband’s wife back to him leading him to decide that it is better to simply join her.

The husband’s inner conflict feeds into the themes of the third instalment “Shit Happens” which is set in a small hospital and revolves around newly qualified nurse Becky (Ayeesha Cervantes) who is seen to be not entirely committed to her new job merely waiting it out until her visa arrives so she can go abroad. Exasperated nurse Reggie (Ricci Rivero) reveals that her predecessor only lasted three days for the same reason while he himself is working a double shift because of short staffing levels. He also accuses her of neglecting her work, avoiding its least pleasant aspects in conveniently forgetting to look in on a patient who had them soiled themselves and needed cleaning up. Beckoned into an alternate reality by the ghost of an old woman, she is soon confronted by her fears covered in poo and vomit while finally abusing the patient who is it seems taking revenge for the neglect she felt at the hands of her doctors while alive. This chapter both underlines the pressures on frontline health workers who are also dealing with their own fears and anxieties along with those of the patients who have no choice other than to trust them, and perhaps also offers direct criticism of those like Becky who only want to escape their responsibilities through chasing more lucrative work abroad.

That sort of thinking is also in play in the final story, “HM?”, which is apparently a common abbreviation used in online selling meaning “how much?” and later takes on a different nuance when the heroine stumbles on a secret Russian food additive that must only be used in small quantities, as we discover, because it is extremely addictive turning those who overindulge into rabid zombies who lose all sense of reason trampling over each other to ease their craving. Widowed single mother Princess (Donna Cariaga) was in a difficult position having lost her job when ABS-CBN lost its media broadcast licence because of the political realities of Duterte’s Philippines and struggling to find a new one in the difficult economic conditions of the pandemic. Like many she decided to start an online side hustle as a home cook despite having no previous experience or talent but finds unexpected success thanks to the Russian serum only for the situation to get out of hand leaving her unable to cope with the demand on her business not to mention the zombified hordes who soon descend on her home.

A fly buzzes through each of the instalments as if signalling the lingering malaise from class-based paranoia to pure desperation and the temptation of a quick fix. Inspired by original stories from Michiko Yamamoto, each of the tales paint a less than flattering picture of the contemporary society not limited to the stresses and strains of life in the middle of a pandemic but only exacerbated by them as pretty much everyone finds themselves trapped in a maddening world that no longer makes sense with no clear sign towards a wholly acceptable way out.

Rabid streams worldwide until 30th April as part of this year’s Udine Far East Film Festival.

Original trailer (English subtitles)