Sasori had been dormant for a decade before being resurrected in this Hong Kong co-production directed by Joe Ma. She is, however, a very different Nami Matsushima (Mizuno Miki) who becomes less a feminist avenger than a sociopathic killer, albeit one fixated on revenge and with ambivalent feelings towards her former lover, Hei Tai (Dylan Kuo Pin-Chao), who evidently did not have enough faith in her to realise that she didn’t murder his entire family just because she felt like it.

Nevertheless, in contrast to other Namis, she did make the decision to do it and went through with stabbing Hei Tai’s sister in the heart right in front of him even if she did it to protect him from the crooks who’d invaded their home. Motives are never explicitly explained, but it’s later suggested that Hei Tai’s professor father may have been knocked off by a rival scholar/gangster researching “inhuman organ treatment”. In any case, the goons that break into her home sexually assault Nami and tell her the only way to save Hei Tai is to help them kill his father and sister. Unfortunately, Hei Tai does not seem to recognise the position she was in nor her transgressive love for him, so is filled with boiling rage and resentment. Curiously, Nami never actually explains either, but is by that point mired in a women’s prison where she contends with the sleazy warden (Lam Suet) and the cellblock’s toughest lady, Dieyou (Natsume Nana), through the medium of cage-based mud wrestling.

This Nami’s transformation is obvious when she rips the loose skull fragment from a woman with learning difficulties she’s befriended and uses it to kill Dieyou. The moment at which she kills Dieyou’s sister, a woman she has no quarrel with, solely to unbalance her rival is presented as a kind of climax in which Nami herself appears to get off on the act of killing. During this earlier stretch of the film, Nami’s victims are largely female and killed for petty reasons. Seemingly cowed and beaten down, she does what the warden says rather than opposing him or like other Nami’s stabbing him in an eye.

This does, however, eventually allow her to escape if as a corpse rescued by a mysterious “corpse collector” (Simon Yam Tat-Wah) who gifts her a Japanese sword and teaches her kung fu so she can achieve her revenge. It’s at this moment that she becomes a kind of supernaturally powered embodiment of vengeance, but it’s immediately made clear that the only revenge she seeks is personal. Spotting a pimp kicking a sex worker in the street, she strikes him down but only tells the sex worker that she doesn’t plan to kill her too otherwise making no further attempt to help her. Ma then takes the action back to its manga roots, relying on obvious wirework to lend a kind of unreality to the fight scenes even if the hand-to-hand combat is generally more realistic.

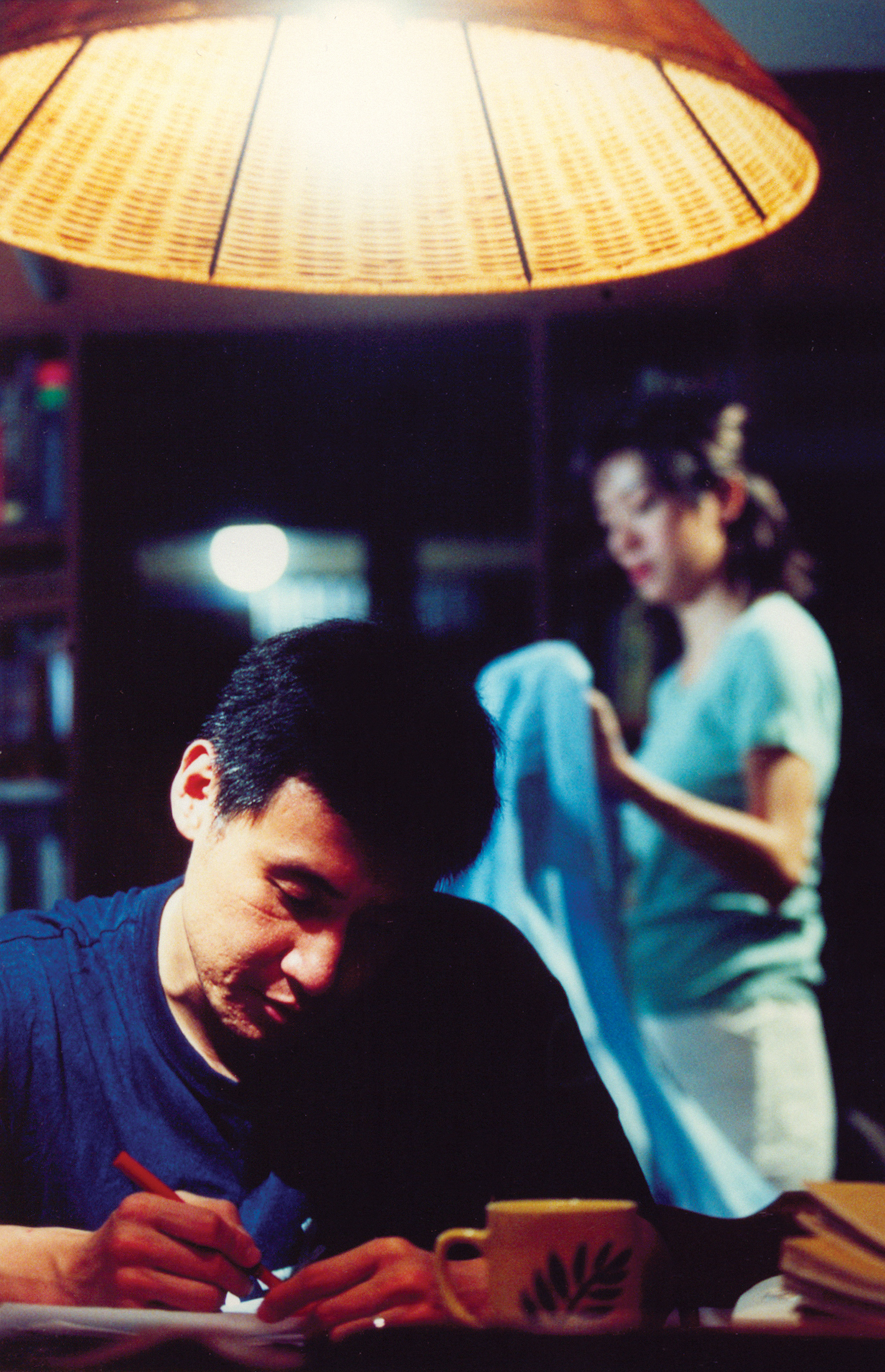

But at the same time, Nami steps into a more arthouse space in a meditation on time and memory that seems to be borrowing a little from Old Boy or perhaps 2046 as she walks into a bar where the barman tells her that he can hypnotise people to erase their memories though he doesn’t they should. Re-encountering Hei Tai who no longer remembers her or his past life as a policeman, she finds herself ambivalent about her revenge, on one level resenting him and on another wondering if she has the right to start over without the problematic fact of her having been responsible for the deaths of Hei Tai’s whole family.

There are many things that don’t really make all that much sense, from the inhuman organ research to Hei Tai’s possibly selective amnesia. Nevertheless, Ma piles on the style with a particularly 2000s Hong Kong aesthetic with its neon lighting and woozy camera work but also adopts a retro sensibility brought out by the use of mainly post-sync sound in which the Japanese actors are dubbed into Cantonese. By the film’s conclusion, Nami has once again become a legend but this time a much less palatable one not so much avenger for an oppressed minority as a cold-blooded and sadistic vigilante interested in little more than personal revenge.

International trailer