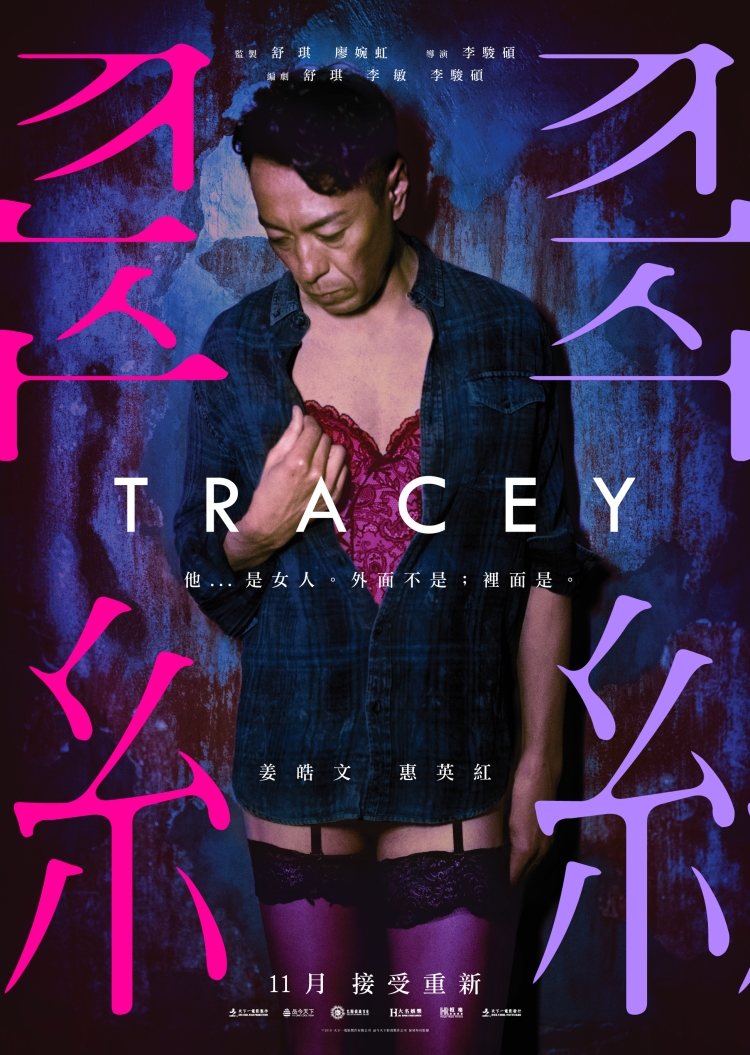

Hong Kong has often sought to present itself through its cinema as an ultramodern, cosmopolitan city, claiming a kind of cultural freedom from Mainland oppression. In truth, however, there are areas in which it may disappoint itself. Jun Li’s debut feature, Tracey (翠絲), is in many ways an empathetic attempt to redress the balance in making plain the destabilising effect emotional repression can exert across an entire society, causing nothing other than the mutual unhappiness which provokes one person to oppress another in service of nothing more than conventionality.

Hong Kong has often sought to present itself through its cinema as an ultramodern, cosmopolitan city, claiming a kind of cultural freedom from Mainland oppression. In truth, however, there are areas in which it may disappoint itself. Jun Li’s debut feature, Tracey (翠絲), is in many ways an empathetic attempt to redress the balance in making plain the destabilising effect emotional repression can exert across an entire society, causing nothing other than the mutual unhappiness which provokes one person to oppress another in service of nothing more than conventionality.

A married, 50-something father of two grown up children, Tai-hung’s (Philip Keung) conventional, ordered life is disrupted when he receives a phone call telling him that a treasured childhood friend, Ching, has been killed while working in Syria as a war photographer. Unbeknownst to anyone, and not quite admitted even to himself, Ching had been the love of Tai-hung’s life and his death finally forces him into a reconsideration of the feelings which are now, perhaps, a lost opportunity. The sense of loss is doubly brought home when he collects Ching’s partner, Bond (River Huang), from the airport and discovers that he had been legally married to another man in the UK though the pair’s marriage certificate is not valid in Hong Kong which presents a problem in trying to repatriate Ching’s ashes.

Bond, himself from Singapore where homosexuality is at least technically still illegal, knew of Ching’s love for Tai-hung and Tai-hung’s unrealised attraction to Ching but struggles with Tai-hung’s decision to not to embrace his sexuality, preferring to marry and have children in pursuit of a conventional life. Despite having grown up in an arguably even more oppressive society, Bond is 20 years younger and has perhaps benefitted from an increasingly liberal world in which greater awareness has afforded him the vocabulary to process Tai-hung’s complex identity with a delicacy that was not available to Tai-hung in his youth, nor to his quasi-mentor Brother Darling (Ben Yuen) – a performer of Chinese Opera who specialised in female roles and confided to Tai-hung that he identified as a woman but is unlikely to have ever come across the term “transgender” let alone claim it as an identity.

Nevertheless, Bond’s arrival begins to push Tai-hung’s long repressed longing to the surface even if his first attempt to explain to Bond that he too identifies as a woman is met with mild derision as Bond misunderstands him in assuming his claiming of a female identity is an attempt to reject his homosexuality. What Tai-hung tries to explain to him is that he does not see himself as a gay man but a straight woman and therefore felt that pursuing his love for Ching, a man who loved men, would never have been a possibility. Fearing his gender identity would never be accepted by anyone, Tai-hung kept his true self hidden even from his closest friends and unwittingly placed a wedge between himself and the man he loved.

Bond pushes him still further with the perhaps unfair charge that his entire life has been essentially selfish and founded on the continued deception of his wife and children. Despite its seeming conventionality, Tai-hung’s family life is not altogether happy. His wife, Anne (Kara Hui), is a fiercely conservative sort who prizes nothing so highly as respectability as she proves by rifling through the maid’s room in search of evidence of sexual indiscretion which she later uses as grounds to suggest firing her. As the couple’s son Vincent (Ng Siu-hin) points out, there is also an unpleasant racial component to her puritanical morality which objects to her Indonesian maid having a right to a private life, fearing that she will bring “disease” into the house by sleeping with another “foreigner”. This is perhaps why she objects to her pregnant daughter’s (Jennifer Yu) desire to divorce her highflying lawyer husband when she discovers that his serial philandering has resulted in a sexually transmitted disease which he has passed to her and which has thankfully been detected early enough to avoid harming the baby.

Despite Anne’s pleas with her daughter that you don’t reject someone for turning out to be different than you assumed them to be, she is obviously not ready to accept Tai-hung’s authentic self despite having been aware that there was always something slightly amiss within their marriage which prevented it from being a true and total union. It is perhaps this sense of nagging incompleteness and unhappiness which has pushed Anne’s need for respectable conventionality into overdrive, as if a superficially successful adherence to the rules could be a substitute for emotional fulfilment. Her own suffering then seeks to push her daughter into the same space as a self-sacrificing housewife who has exchanged personal happiness for the cold comfort of social respectability.

Thanks to reuniting with a now elderly Brother Darling and finding himself accepted by the younger Bond, Tai-hung begins to find the courage to embrace his true self and discovers that many of his friends and relatives are more supportive than he might have assumed even if some of them may need time to get over the initial shock. As his mother tells him, the important thing in life is learning to find one’s peace of mind – something which could only be helped by abandoning the outdated Confucian ideas which continue to define the social order in favour of something warmer, freer, and fairer built on mutual acceptance and compassion.

Tracey screens as the closing night gala of the eighth season of Chicago’s Asian Pop-Up Cinema on April 24, 7pm, at AMC River East 21. It will also be screened in London as the closing night of this year’s Chinese Visual Festival on 9th May, 6pm, at BFI Southbank where members of the cast and crew will be attendance for a Q&A.

Original trailer (English subtitles)