The third and final instalment in the General’s Son trilogy picks up some time after the events of the previous film, not with Doo-han (Park Sang-min) being released from prison but emerging from hiding. After his showdown with Kunimoto, he’d been lying low in a temple but is now on the run, heroically jumping off a train to avoid the police and thereafter making his way to Wonsan and seeking asylum with an affiliated gang. By this time, Doo-han’s role as the son of a legendary general who was murdered by communist traitors while fighting bravely for independence seems to have been forgotten as he wanders around trying to evade the colonial net.

In Wonsan, he immediately starts causing trouble by objecting to gang leader Shirai’s treatment of an aspiring singer, Eun-sil (Oh Yeon-soo), whom he has more or less imprisoned until she agrees to sleep with him. Doo-han helps her to escape and encourages her to continue pursuing her dreams of stardom, but motions toward romance create an ongoing instability which indirectly echoes throughout the rest of the film as he tries to balance his desire for Eun-sil with the ongoing battle for Jongno and resistance against the Japanese.

For her part, Eun-sil falls for Doo-han as the man who saved her from Shirai and restored her freedom but still finds herself at the mercy of the Japanese as otherwise sympathetic lieutenant Gondo (Dokgo Young-jae) takes a liking to her after being struck by her singing talent which he apparently did not expect seeing as she is a mere Korean. Later Gondo and Doo-han become accidental rivals when Eun-sil is arrested because of her associations with Doo-han and they have to work together to get her out. Gondo is fiercely critical of their relationship, not only out of romantic jealously but because he finds the Korean approach to romance vulgar. Despite her later agency which sees her primed to reject both men in order to pursue her career, Eun-sil is also a mere device to emphasise Doo-han’s virility as the entire neighbourhood is kept awake by her moans of ecstasy even after Doo-han has been badly injured in a fight, is covered in bandages, and has been told he will need to stay in bed for the next month to recover.

Gondo meanwhile, in a slightly symbolic gesture, tries to force Eun-sil to marry him by laying his sword on the table and making it plain that if she refuses he will kill her and then himself. Perhaps in a more romantic tale, he might have threatened Doo-han and asked her to make a sacrifice, but in any case Doo-han tries something much the same on hearing the news, having a kitchen knife brought to him and thrusting it into the table. Eun-sil merely seems amused, or perhaps worryingly pleased at open show of romantic jealousy as proof of love, knowing that it is quite unlikely Doo-han is actually going to hurt her (the same cannot be said for Gondo). He still however tries to command her to stay and marry him, refusing to let her leave because she is “his”, but in the end of course it’s bluster and if she chooses to leave he cannot stop her because he is not a man like Shirai or Gondo who would willingly restrict another’s freedom. He is still “fighting for our liberty” after all.

Meanwhile, he undergoes a parallel “romance” with Dong-hae (Lee Il-jae) who left alone for Manchuria after renouncing the gangster life but has apparently left the Independence Movement because it was too socialist when what he seems to want is individual capitalist prosperity which is why he’s got mixed up in the opium trade. Still on the run, Doo-han seeks out Double Blade, the street thug mentor who brought him into the gang all those years ago. Unfortunately he makes a lot of trouble for Double Blade in annoying one of his underlings who runs a local Chinese gang and then starting a turf war after getting himself into trouble with the bandits who run the drugs trade. He and Dong-hae are eventually separated in the escape from the bandits but reunite when Hayashi (Shin Hyun-joon), who is still nominally running the yakuza but has delegated Jongno to his sadistic brother-in-law Uda, tries to use him in a plot to take out Doo-han once and for all.

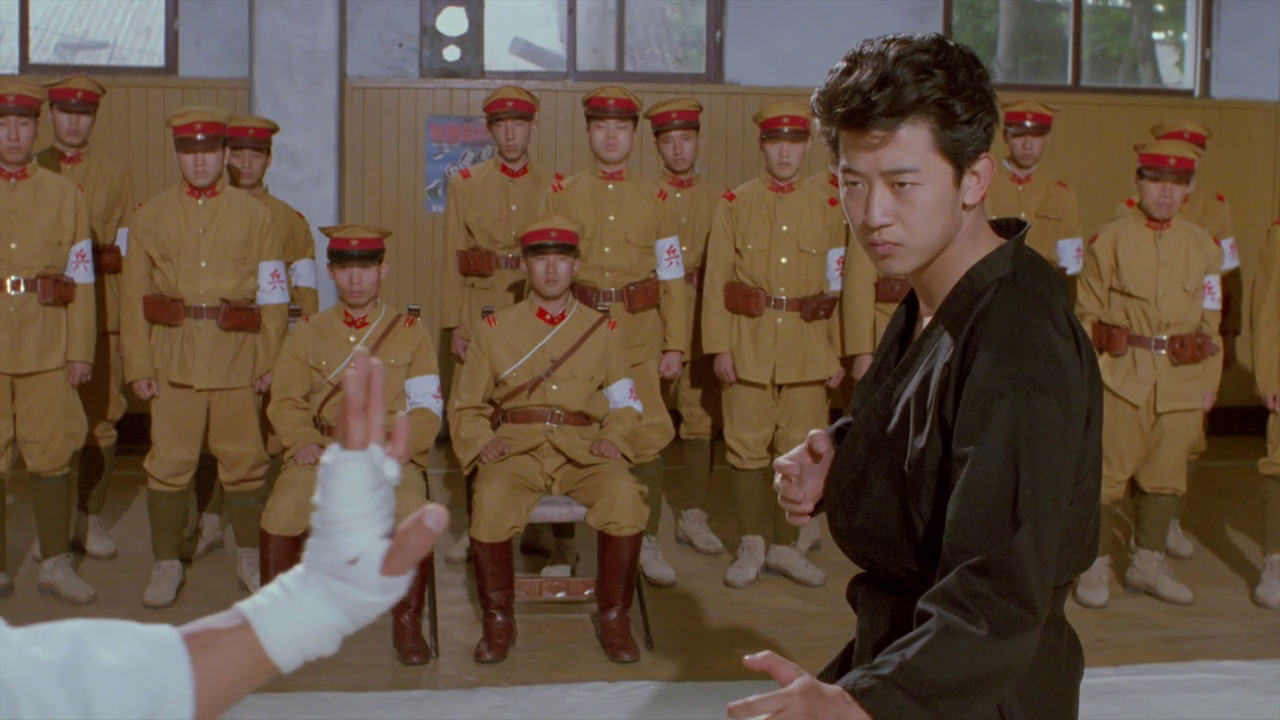

Throughout the series, Doo-han has been a mythic, comic book-style hero who is respected for the integrity of his fists, refusing to use weapons and leaving his opponents beaten but breathing so that they can verbally concede the victory. The previous film had seen him enact a more serious kind of violence, but even so his rival apparently survived only permanently changed. His final confrontation with Hayashi, by contrast, sees him kill for the first time by picking up a blade and then a gun. Nevertheless, he is perhaps the General’s Son after all. According to his gang members, scattered after he left, he is the only force with can keep Jongno free, without him they fell apart and let the Japanese take their streets from them. The final instalment in Doo-han’s story ends on a moment of tempered victory which avenges his gangster honour but places him firmly in the arms of his brother Dong-hae as they temporarily retreat from the battlefield towards an increasingly unstable future.