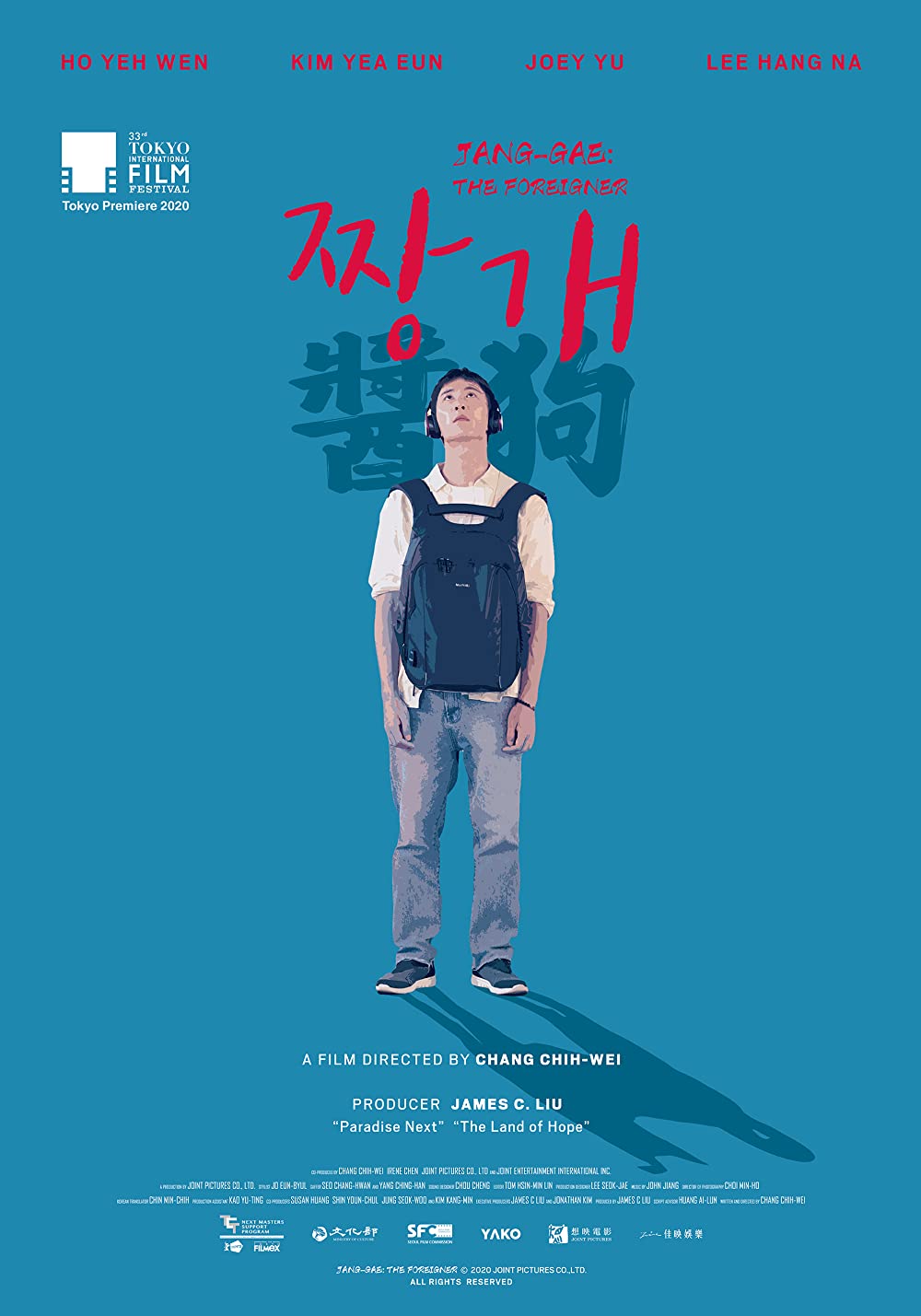

An angry young man struggles to repair his fracturing sense of identity in Chang Chih-Wei’s provocatively titled Jang-gae: The Foreigner (醬狗, jiàng gǒu). “Jang-gae” is in itself a derogatory term for Korean-Chinese translated literally as “sauce dog”, while the film’s hero Gwang-yong (Ho Yeh-wen) feels himself to be a perpetual outsider continually othered in Korea but having little affinity for his Chinese roots and dreaming of a future in the US having been short-listed for a scholarship programme only to be confronted with the contradictions of his identity when his father is taken ill and having the wrong kind of passport may jeopardise his dreams of going abroad.

For reasons unknown to him, Gwang-yong’s father Seo-sang (Joey Yu) pulled him out of the Chinese-medium school he’d been studying at and moved him to a regular Korean high school instead. Although a straight-A student and in fact the class monitor, Gwang-yong experiences constant xenophobic microaggressions from his classmates who sarcastically repeat the common Chinese greeting “Have you eaten yet?” and refer to him as “sauce dog” while the teacher expresses surprise that “even a foreigner like Gwang-yong” has mastered Korean history. The teacher’s remark is quite ironic in that Gwang-yong may have a Taiwanese passport but he was born and raised in Korea, as, it happens, was his father. In fact, his family has no real connection with Taiwan, his grandfather fled Mainland China during the civil war and presumably applied for a Republic of China passport as a supporter of the Nationalist Party. In any case, his passport is also a non-citizen one which grants no right of abode because his family has no household registration in Taiwan meaning in essence that Gwang-yong is stateless and has no citizenship of any sort.

For obvious practical reasons, he wants to apply for a Korean passport which he’s entitled to by right of birth as his mother is a Korean citizen but his father won’t have it. Meanwhile, despite bullying him the other boys all complain that foreigners have it easy believing that he got a leg up in the scholarship scheme for being non-Korean while he’ll also be exempt from the National Exam and military service (which as he points out he’d have to do in Taiwan if he were a full citizen there), but being exempt from each of these requirements for Korean citizens leaves him feeling even more excluded reinforcing the sense that he’s not really a part of the culture in which he has grown up in the only country he’s ever known. He tells his mother that he just wants to live a dignified life in Korea, but is ruffed up by a trio of thuggish men later claiming to be police immigration officers accusing him of overstaying on his visa not so much as even apologising after forcibly pulling his wallet out of his pocket and seeing his birthplace listed as Korea on his ID.

Most of his animosity is directed at his father who speaks to him only in Mandarin and is in general authoritarian and unsupportive, yet his father’s illness also causes him to lash out at his mother laying bare his own internalised shame in berating her for having married someone who was Korean-Chinese as if all his problems would have been solved if she’d only married somebody Korean, blaming her rather than standing up against the xenophobia and prejudice which pervade his society. Meanwhile the girl he has a crush on at school, Ji-eun (Kim Yea-eun) who is also an outcast having moved schools after the grandmother who was raising her passed away, just wants to get out of “Hell Joseon” and doesn’t much care where to. He points out swapping Hell Joseon for Taiwan’s “Ghost Island” might not make much difference, but discovers that his accidental statelessness leaves him doubly disadvantaged denied his full rights in either place while equally unable to escape.

Even so his father’s illness forces him to reconsider not only his relationship to him but to his Chinese heritage along with the Korean, Ji-eun also reminding him that the people who make it in Korean society are the ones who learn to stand up for themselves which perhaps informs his final act of rebellion against the bullies no longer willing to be meek or apologetic but directly challenging their attempts to intimidate him having gained a new confidence. A gentle coming-of-age tale in which a young man comes to understand both his father and his heritage Jang-Gae: The Foreigner never shies away from the problems faced by ethnic minorities in contemporary Korea nor the inequalities of the non-citizen passport but does allow its conflicted hero to find a degree of equilibrium in himself secure in his own identity.

Jang-Gae: The Foreigner streamed as part of the 14th season of Asian Pop-Up Cinema.

Original trailer (English subtitles)