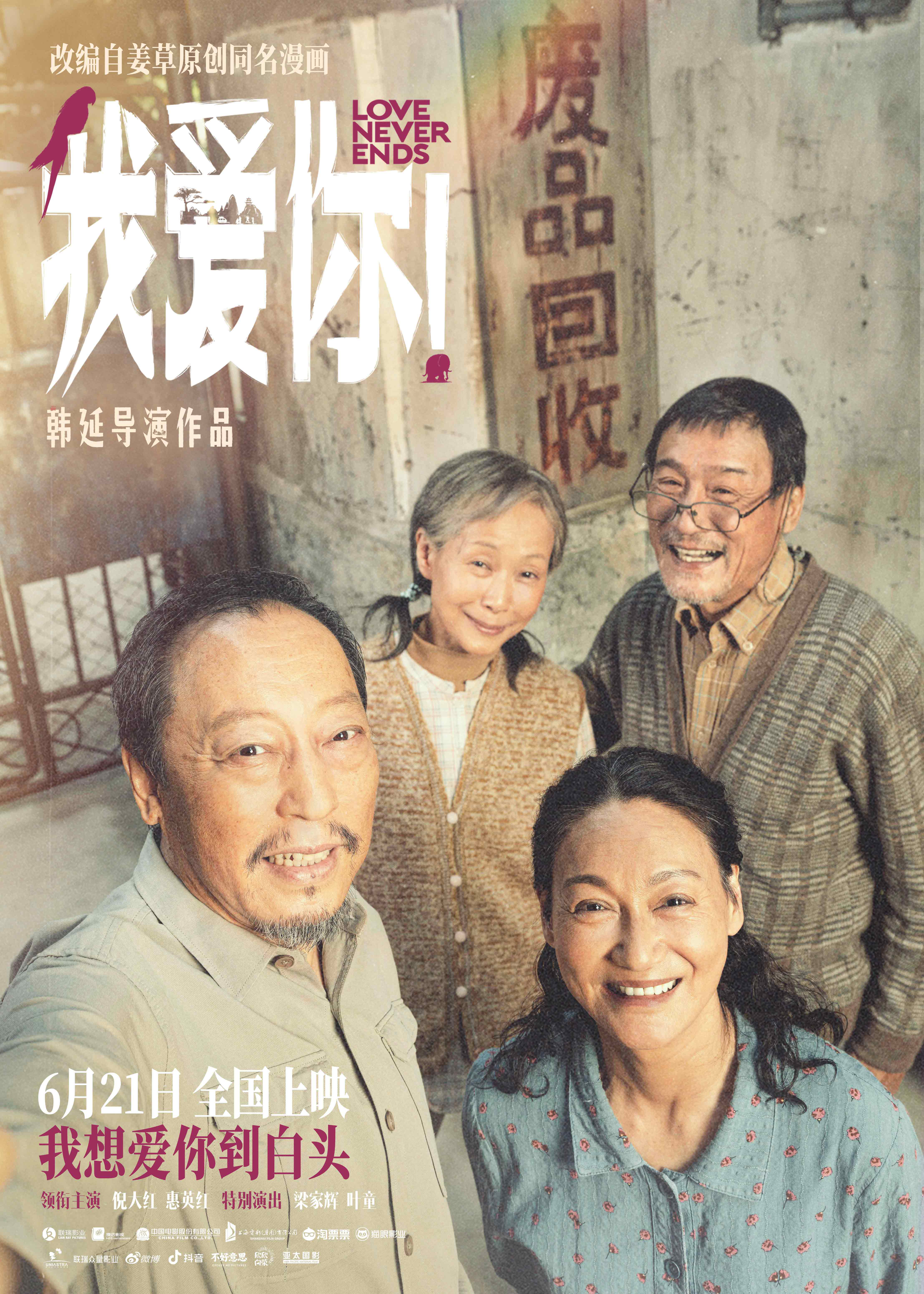

The generational tensions in the contemporary society are gradually exposed when a retired mechanic begins to fall for a feisty widow in Han Yan’s quietly affecting romantic dramedy, Love Never Ends (我爱你!, wǒ ài nǐ). Based on a Korean webtoon by Kang Full the Chinese title “I Love You!” hints at its true intentions along with the potential for incongruity when exploring romantic courtship among the older population even as the film hints at the destructive cycles of repression and lost love in a still conservative culture.

Something of a rebel, widower Wenjie (Ni Dahong) walks around with a chain whip clipped to his belt that should probably be illegal. He likes to get it out every now and then to whirl around while talking like the hero of a martial arts serial, claiming that his whip exists for truth and justice so he’s going to use it to punish unfilial children and heartless bullies. Quite frankly, it’s ridiculous and on this particular occasion he chooses the wrong side coming to the defence of a park manager who’s trying to move a pair of elderly scrap collectors on because inspectors will soon be arriving and he’s worried their presence will make him look bad. Wenjie mock slaps the woman, Ru (Kara Hui Ying-Hung), stopping his hand just before connecting with her face and then shatters her jade bracelet with the whip. It’s fair to say they don’t get off on the best foot, which is unfortunate as Wenjie soon discovers she is the carer for a former Cantonese opera star, Mrs Qiu (Lu Qiuping), his daughter desperately wants to take on her son, Sai, as a pupil.

In one sense, the scene makes plain the battle for the use of space in urban environment, Wenjie insisting the park is for “everyone” to exercise, but simultaneously suggesting that Ru and her friend Dingshan (Tony Leung Ka-Fai) have no right to use it. Meanwhile, it becomes clear that Wenjie is also rebelling against a kind of infantilisation at the hands of his well-meaning children who have put up a surveillance camera in his home to make sure he isn’t drinking alcohol while his doctor also breaks medical ethics by immediately calling to tell them that the security system hasn’t worked because whatever he says Wenjie has obviously been continuing to drink. It may be for his own good, but a role reversal has taken place as his children exercise all the power not just over his life but their own chidren’s too. Wenjie’s teenage granddaughter wants to study abroad to reunite with her boyfriend, but her parents don’t approve echoing the sad story of Ru who once came from a moderately wealthy village family and eloped with a painter when her parents pressured her to accept an arranged marriage to the headman’s son only for the painter to die not long afterwards leaving her all alone in an unfamiliar city.

Mrs Qiu too has her own sad romance in having been prevented from marrying her childhood sweetheart because of parental opposition. Despite her illustrious career, she eventually became a heartbroken recluse while her lover, Chen (Bao Yinglin), was driven out of his mind and has spent his whole life in a psychiatric hospital pushing a wooden mannequin around believing it to be Qiu save for the heartbreaking moments of lucidity in which he realises the truth. Dingshan, meanwhile, is lovingly caring for his wife who has advanced dementia and cannot bear the thought of being parted from her while she continues to dwell on a sense of guilt that her older children felt neglected that they had to spend what little they had trying to cure their youngest daughter’s illness though it eventually resulted in the loss of her hearing because they could not treat it fast enough.

The children are, however, largely ungrateful. The sons barely visit them and are each a little repulsed by their parents’ humbleness, more or less ignoring them at their 45th anniversary celebration while one of the daughters-in-law sprays disinfectant everywhere as if she thinks this place is dirty and a danger to her children. Wenjie can barely contain himself on witnessing such unfiliality and perhaps comes to reflect that his children’s micromanaging is at least better than the total indifference of Dingshan’s sons and daughters though they suffered so much more to raise them. He blames himself for his wife’s death worried that she didn’t tell him she was in pain until it was too late or worse that she did and he didn’t listen, while uncertain how to pursue a new romance with Ru just as she wonders if Chen and Qiu are really the lucky ones living in an endless fantasy of romantic love. Conversely, she’s afraid of romance because it will inevitably lead to the pain of separation and she isn’t sure it’s worth it in the time she has left.

Then again, Wenjie has a youthful quality, shifting from the wuxia speak of his mission for justice to embrace the new internet lingo of his grandchildren along with its meme culture before following his granddaughter’s lead in deciding to please himself rather than those around him by saying how he really feels even if it’s a bit awkward or embarrassing. A minor subplot about the inheritance of traditional culture echoes the intergenerational themes as little Sai resolves to learn from the previous generation in order to pass it on to the next, while Ru and Wenjie finally come to an acceptance of living in the moment that even if it eventually leads to heartbreak there’s no point being unhappy now too.

Original trailer (Simplified Chinese & English subtitles)