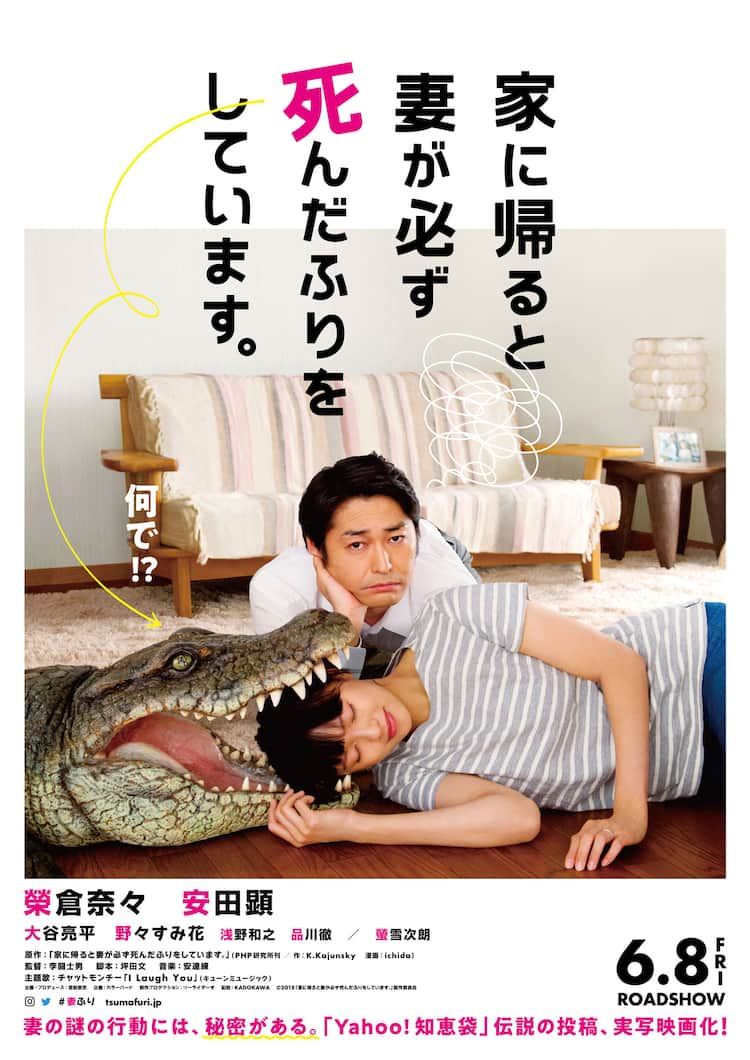

“If you give it some time it becomes just right,” according to the eccentric wife in Toshio Lee’s quirky contemplation of the modern marriage, When I Get Home, My Wife Always Pretends to be Dead (家に帰ると妻が必ず死んだふりをしています。Ie ni kaeru to tsuma ga kanarazu shinda furi wo shite imasu.). A more cheerful take on Harold and Maude, Lee’s not quite newlywed couple are heading out of their honeymoon phase and perhaps harbouring twin anxieties as they face the three year itch and start to wonder what marriage is all about and if they have what it takes to go the distance.

Regular salaryman Jun (Ken Yasuda) is particularly preoccupied with the “three year wall” because he was married once before and the relationship failed at the three year level which is, coincidentally, when many small businesses and restaurants fail. Perhaps unusually he has a friend at work, Sano (Ryohei Ohtani), with whom he discusses his marriage who ironically points out that Jun is essentially thinking of his marital status in the same way as a “contract renewal” as if worried he’s about to be let go. Around this time, however, he gets a nasty shock on returning home discovering his wife Chie (Nana Eikura) lying on the living room floor covered in blood. Distraught, he struggles to remember the number to call an ambulance only for Chie to suddenly burst out laughing. The same thing begins happening to him every time he goes home with the scenarios becoming increasingly elaborate such as being eaten by an alligator, for example, or being abducted by aliens. All things considered, Jun is quite a dull man, too embarrassed even to let his wife kiss him goodbye on the doorstep lest it scandalise the neighbours, so all of this fantasy is doing his head in but his rather blunt hinting that he’d prefer it Chie stop with the playing dead stuff only seems to hurt her feelings while she shows no signs of abandoning her strange hobby.

Part of the problem is that Jun is also intensely self-involved and perhaps the product of a conformist, patriarchal society. He never reveals the reasons why his first marriage failed, only that his wife abruptly left him without much of an explanation. It never seems to occur to him that Chie may be fixating on death because she lost her mother young, possibly around the same age she is now, and is in a sense role playing demise to ease her anxiety probably grateful each time he returns home and “saves” her. For his part he insists he doesn’t “need excitement” and wants “a normal wife”, desperate to appear conventional and paranoid that Chie is going out of her mind. Rather than fully see her he keeps trying to “fix” the problem by encouraging her to take a part-time job and make new friends, worried she’s bored at home and lonely after moving away from her family home in Shizuoka.

His friend Sano, seemingly happily married for five years, has a much more relaxed attitude to the mysteries of marriage but as the two wives begin to bond the cracks in their respective relationships are gradually revealed. Like Jun, Sano is also a conventional salaryman with traditional ideas about marriage which he somewhat rudely exposes in thinking he’s doing Jun a favour by “explaining” to Chie that her hobby is offensive to Jun because men work hard all day and want to sit down quietly without any bother when they come home. His quiet word provokes an outburst in his own wife Yumiko (Sumika Nono) who can no longer bear the irony, asking him why it is that she’s supposed to tiptoe around because he’s “tired” as if she does nothing at all day just waiting for him to come home. It’s as if they think their wives go back in the box until they ring the doorbell in the evening and wake them up again, as if the only value in their existence lies in supporting their husbands. Sano is mildly shocked on witnessing Yumiko suddenly brighten and embark on a mini lecture of crocodile facts after catching sight of Chie’s prop (bought on sale, making the most of her thrifty housewife skills), totally unaware she was into reptiles and equally stunned to learn she’s also a karate master. Five years, and it’s like they’re strangers.

“Thinking won’t give you answers, when you don’t know, ask,” advises Jun’s boss, constantly carping about his ungrateful wife but later revealing that his deep love for her is what’s kept him going all these years. Miscommunication lies at the root of all their problems, Jun even failing to identify the most common if poetic of cliched idioms in his wife’s tendency to remark on the beauty of the moon seemingly at random. Clued in a little by Chie’s patient father, Jun begins to wake up himself, finally seeing his wife and understanding that she’s been trying to tell him something all this time only he was too self-involved to notice. “You can always find me if you look,” Chie was fond of saying, indirectly hinting that marital bliss is a matter of mutual recognition aided by empathy and a willingness to be foolish in the pursuit of happiness.

When I Get Home, My Wife Always Pretends to be Dead is available to stream in the UK via Terracotta

Original trailer (English subtitles)

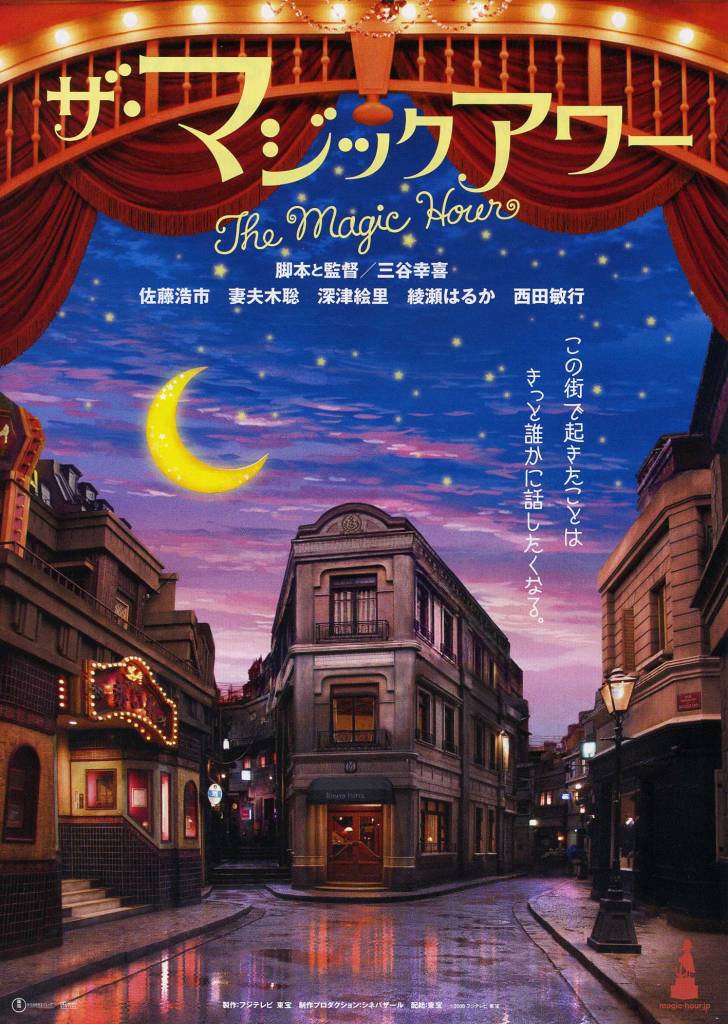

If there’s one thing you can say about the work of Japan’s great comedy master Koki Mitani, it’s that he knows his cinema. Nowhere is the abundant love of classic cinema tropes more apparent than in 2008’s The Magic Hour (ザ・マジックアワー) which takes the form of an absurdist meta comedy mixing everything from American ‘20s gangster flicks to film noir and screwball comedy to create the ultimate homage to the golden age of the silver screen.

If there’s one thing you can say about the work of Japan’s great comedy master Koki Mitani, it’s that he knows his cinema. Nowhere is the abundant love of classic cinema tropes more apparent than in 2008’s The Magic Hour (ザ・マジックアワー) which takes the form of an absurdist meta comedy mixing everything from American ‘20s gangster flicks to film noir and screwball comedy to create the ultimate homage to the golden age of the silver screen.