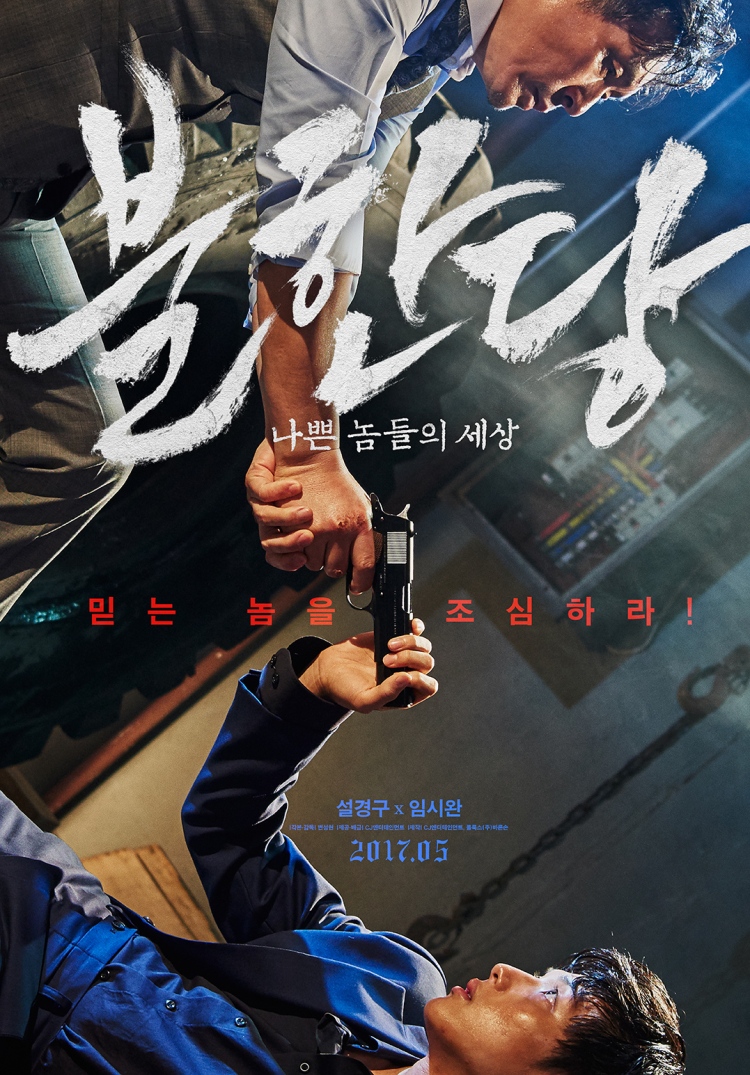

Heroic bloodshed is alive and well and living in Korea. The strange love child of Na Hyun’s The Prison, and Park Hoon-jung’s New World, the first gangster action drama from Byun Sung-hyun (previously known for light comedies), The Merciless (불한당: 나쁜 놈들의 세상, Boolhandang: Nabbeun Nomdeului Sesang) more than lives up to its name in its noirish depiction of genuine connection undercut by the inevitability of betrayal. Inspired as much by ‘80s Hong Kong cinema with its ambitious, posturing tough guys and dodgy cops as by the more immediate influence of the seminal Infernal Affairs, Byun’s brutal tale of chivalry is, as he freely admits, an exercise in style, but its aesthetics do, at least, help to elevate the otherwise generic narrative.

Heroic bloodshed is alive and well and living in Korea. The strange love child of Na Hyun’s The Prison, and Park Hoon-jung’s New World, the first gangster action drama from Byun Sung-hyun (previously known for light comedies), The Merciless (불한당: 나쁜 놈들의 세상, Boolhandang: Nabbeun Nomdeului Sesang) more than lives up to its name in its noirish depiction of genuine connection undercut by the inevitability of betrayal. Inspired as much by ‘80s Hong Kong cinema with its ambitious, posturing tough guys and dodgy cops as by the more immediate influence of the seminal Infernal Affairs, Byun’s brutal tale of chivalry is, as he freely admits, an exercise in style, but its aesthetics do, at least, help to elevate the otherwise generic narrative.

That would be – the complicated relationship between young rookie Hyun-su (Im Siwan) and grizzled veteran Jae-ho (Sol Kyung-gu). Hyun-su proves himself in prison by besting current champions bringing him to the attention of Jae-ho – the de facto prison king. Sharing similar aspirations, the pair form a tight, brotherly bond as they hatch a not so secret plan to take out Jae-ho’s boss, Ko (Lee Kyoung-young), leaving Jae-ho a clear path to the top spot of a gang engaged in a lucrative smuggling operation run in co-operation with the Russian mob and using the area’s fishing industry as an unlikely cover.

We’re first introduced to Jae-ho through reputation in the film’s darkly comic opening scene in which Ko’s resentful, cowardly nephew Byung-gab (Kim Hee-won), has a strange conversation with a soon to be eliminated colleague. Byung-gab says he finds it hard to eat fish with their tiny eyes staring back at you in judgement. He admires Jae-ho for his ice cold approach to killing, meeting his targets’ gaze and pulling the trigger without a second thought.

Jae-ho is, indeed, merciless, and willing to stop at nothing to ensure his own rise through the criminal underworld. He will, however, not find it so easy to pull that trigger when he’s staring into the eyes of sometime partner Hyun-su. Neither of the two men has been entirely honest with the other, each playing a different angle than it might at first seem but then caught by a genuine feeling of brotherhood and trapped in storm of existential confusion when it comes to their individual end goals. Offering some fatherly advice to Hyun-su, Jae-ho recites a traumatic childhood story and cautions him to trust not the man but the circumstances. Yet there is “trust” of a kind existing between the two men even if it’s only trust in the fact they will surely be betrayed.

Byun rejoices in the abundance of reversals and backstabbings, piling flashbacks on flashbacks to reveal deeper layers and hidden details offering a series of clues as to where Jae-ho and Hyun-su’s difficult path may take them. Truth be told, some of these minor twists are overly signposted and disappointingly obvious given the way they are eventually revealed, but perhaps when the central narrative is so fiendishly convoluted a degree of predictability is necessary.

The Merciless has no real political intentions, but does offer a minor comment on political necessity in its bizarre obsession with the fishing industry. The police know the Russians are involved in drug smuggling and using the local fishing harbour as a front, but as fishing rights are important and the economy of primary importance they’d rather not risk causing a diplomatic incident by rocking the boat, so to speak. The sole female presence in the film (aside from Hyun-su’s sickly mother), determined yet compromised police chief Cheon (Jeon Hye-jin), is the only one not willing to bow to political concerns but her methods are anything other than clean as she plants seemingly vast numbers of undercover cops in Jae-ho’s outfit, only to find herself at the “mercy” of vacillating loyalties.

Heavily stylised, Byun’s action debut does not quite achieve the level of pathos it strives for in an underwhelming emotional finale but still manages to draw out the painful connection between the two anti-heroes as they each experience a final epiphany. An atmosphere of mistrust pervades, as it does in all good film noir, but the central tragedy is not in trust misplaced but trust manifesting as a kind of love between two men engulfed by a web of confusion, betrayal, and corrupted identities.

Screening as part of the London Korean Film Festival 2017 at Regent Street Cinema on 3rd November, 6.30pm. The Merciless will also screen at:

- Broadway Cinema, Nottingham, 10 November, 6.30 pm

- Home, Manchester, 12 November, 8.20 pm

- Queen’s Film Theatre, Belfast, 19 November, 6.20 pm

and will be released by StudioCanal on 13th November.

International trailer (English subtitles)

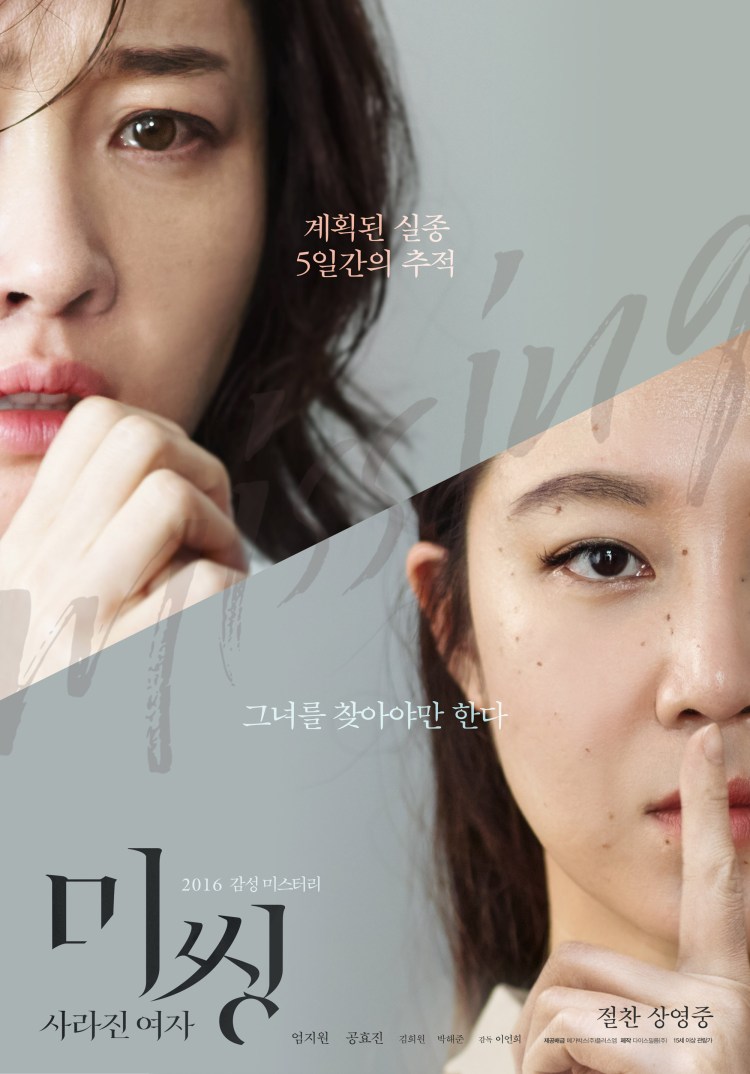

Since ancient times drama has had a preoccupation with motherhood and a need to point fingers at those who aren’t measuring up to social expectation. E Oni’s Missing plays out like a Caucasian Chalk Circle for our times as a privileged woman finds herself in difficult circumstances only to have her precious daughter swept away from her just as it looked as if she would be lost through a series of social disadvantages. Missing is partly a story of motherhood, but also of women and the various ways they find themselves consistently misused, disbelieved, and betrayed. The two women at the centre of the storm, desperate mother Ji-sun (Uhm Ji-won) and her mysterious Chinese nanny Han-mae (Gong Hyo-jin) are both in their own ways tragic figures caught in one frantic moment as a choice is made on each of their behalves which will have terrible, unforeseen and irreversible consequences.

Since ancient times drama has had a preoccupation with motherhood and a need to point fingers at those who aren’t measuring up to social expectation. E Oni’s Missing plays out like a Caucasian Chalk Circle for our times as a privileged woman finds herself in difficult circumstances only to have her precious daughter swept away from her just as it looked as if she would be lost through a series of social disadvantages. Missing is partly a story of motherhood, but also of women and the various ways they find themselves consistently misused, disbelieved, and betrayed. The two women at the centre of the storm, desperate mother Ji-sun (Uhm Ji-won) and her mysterious Chinese nanny Han-mae (Gong Hyo-jin) are both in their own ways tragic figures caught in one frantic moment as a choice is made on each of their behalves which will have terrible, unforeseen and irreversible consequences. Up until very recently, many of us lucky enough to live in nations with entrenched labour laws have had the luxury of taking them for granted. Mandated breaks, holidays, sick pay, strictly regulated working hours and overtime directives – we know our rights, and when we feel they’re being infringed we can go to our union representatives or a government ombudsman to get our grievances heard. If they won’t listen, we have the right to strike. Anyone who’s been paying attention to recent Korean cinema will know that this is not the case everywhere and even trying to join a union can not only lead to charges of communism and loss of employment but effective blacklisting too. Cart (카트), inspired by real events, is the story of one group of women’s attempt to fight back against an absurdly arbitrary and cruel system which forces them to accept constant mistreatment only to treat their contractual agreements with cavalier contempt.

Up until very recently, many of us lucky enough to live in nations with entrenched labour laws have had the luxury of taking them for granted. Mandated breaks, holidays, sick pay, strictly regulated working hours and overtime directives – we know our rights, and when we feel they’re being infringed we can go to our union representatives or a government ombudsman to get our grievances heard. If they won’t listen, we have the right to strike. Anyone who’s been paying attention to recent Korean cinema will know that this is not the case everywhere and even trying to join a union can not only lead to charges of communism and loss of employment but effective blacklisting too. Cart (카트), inspired by real events, is the story of one group of women’s attempt to fight back against an absurdly arbitrary and cruel system which forces them to accept constant mistreatment only to treat their contractual agreements with cavalier contempt. When no time passes, does anything change? Yes, and then again, no, if Um Tae-hwa’s Vanishing Time: A Boy Who Returned (가려진 시간, Garyeojin Shigan) is to be believed. Dealing with the nature of time, connection, and faith Um’s film is a supernaturally tinged fairytale which never seriously entertains the more rational explanation offered by the naysayers, but is filled with the innocence of childhood and the essential naivety of adolescence. Melancholy, though somehow uplifting, Vanishing Time neatly avoids the pitfalls of romantic melodrama for a genuinely affecting coming of age story as its heroine is forced to make peace with her traumatic past through accepting the loss and sacrifice of her present.

When no time passes, does anything change? Yes, and then again, no, if Um Tae-hwa’s Vanishing Time: A Boy Who Returned (가려진 시간, Garyeojin Shigan) is to be believed. Dealing with the nature of time, connection, and faith Um’s film is a supernaturally tinged fairytale which never seriously entertains the more rational explanation offered by the naysayers, but is filled with the innocence of childhood and the essential naivety of adolescence. Melancholy, though somehow uplifting, Vanishing Time neatly avoids the pitfalls of romantic melodrama for a genuinely affecting coming of age story as its heroine is forced to make peace with her traumatic past through accepting the loss and sacrifice of her present.