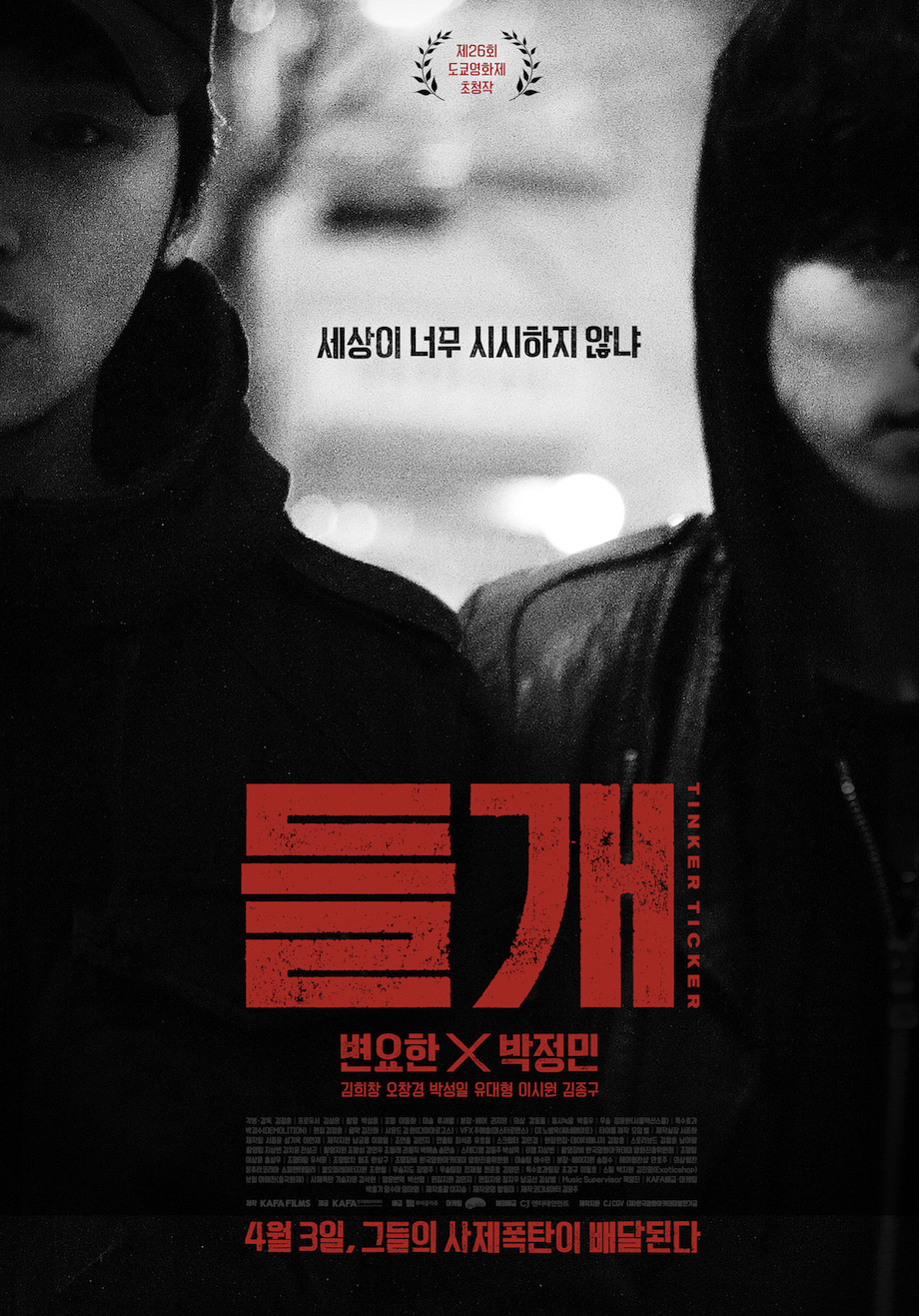

A jaded young man finds himself torn between continuing to fight the system and a total capitulation to it in Kim Jung-hoon’s explosive debut feature Tinker Ticker (들개, Deul-gae). Fit to explode, Jung-gu (Byun Yo-han) takes his revenge on a bullying culture by literally blowing it to hell but after a spell in juvenile detention emerges meek and mild, lacking in resistance and apparently willing to undergo whatever degradations are asked of him in order to achieve conventional success.

Having placed a bomb in the car of a teacher who was abusive towards him, Jung-gu was caught and sent to prison with the unfortunate consequence that he can no longer study chemistry as he’s been banned from using dangerous substances. He repeatedly attends job interviews where he is asked bizarre and invasive questions, but can only find work as a post-graduate teaching assistant to a marketing professor who, like his teacher, largely abuses his position to humiliate him. To ease his frustrations, Jung-gu makes bombs at home but offers to send them out on the internet for free on the condition that the recipient actually use them.

His life changes when he runs into rebellious drop out Hyo-min (Park Jung-min) who is done with capitulation and fully committed to bucking the system. Seemingly from a wealthy family, he’s cut ties with his parents and lives a squalid life in a bedsit while continuing to attend university lectures despite having been expelled. Jun-gu sends one of the bombs to him to see what would happen and though Hyo-min seemed like he was going to simply throw it away he ends up blowing up a van which ironically has the CJ Films logo on the side.

Hyo-min in a sense represents Jung-gu’s rage and resentment towards the system that oppresses him along with a desire for anarchic autonomy while he conversely leans closer to a conventional corporate existence by willingly debasing himself before his sleazy boss Professor Baek (Kim Hee-chang) who asks him to act unethically by “revising” the results of his research so they can secure funding and do a back door deal with his long-standing contact Mr. Kim. Baek also forces him to drink beer that’s been drained through his sock as part of a bizarre hazing ritual while otherwise running him down or insulting him at the office.

Hyo-min tries to goad Jun-gu into blowing up his attempts at conventionality by taking out Baek, but he continues to vacillate apparently still interested in becoming a corporate drone whatever the personal cost. “I don’t want you to become dull,” a slightly spruced up Hyo-min later insists in trying to push Jung-gu into killing Baek, while Jung-gu isn’t sure which life he wants torpedo. In any case, he seems incredibly ashamed of his criminal past and wary of others finding out about it not just because of its practical consequences for his employment but on a personal level. If he wants to transition fully to the life of a soulless salaryman he’ll need to kill the Hyo-min within him and remove all traces of resistance and individuality.

Despite having promised to do so, none of the other men who request the bombs actually use them perhaps like Jung-gu lacking the ability to follow through but enjoying the power of having the ability to burn the world even if they’ll never use it. Jung-gu’s bombing fixation is indeed in its way passive, a vicarious thrill in the ability to cause havoc for no real purpose but not really doing anything with it all while his resentment grows in parallel with his desire to be accepted by mainstream society. Hyo-min eventually comes to the conclusion that nothing really changes, and it both and doesn’t for Jung-gu who finds himself succumbing to the consumerist desires of a capitalistic society willing to debase himself, and later humiliate others, to claim his rightful place on the corporate ladder. Kim takes aim at the pressure cooker society, implying that these young men are in themselves almost ready to explode in their twin resentments and jealousies while ultimately complicit in their own oppression in wilfully stepping in to a corporate straitjacket even at the cost of their freedom and individuality.

Tinker Ticker screened as part of this year’s London Korean Film Festival.

International trailer (English subtitles)

Korea is quite good at rom-coms. Consequently they make quite a lot of them and as the standard is comparatively high you have to admire the versatility on offer. Korean romantic comedies are, however, also a little more conservative, coy even, than those from outside of Asia which makes Petty Romance (쩨쩨한 로맨스, Jjae Jjae Han Romaenseu) something of an exception in its desire to veer in a more risqué direction. He’s too introverted, she’s too aggressive – they need each other to take the edges off, it’s a familiar story but one that works quite well. Petty Romance does not attempt to bring anything new to the usual formula but does make the most of its leads’ well honed chemistry whilst keeping the melodrama to a minimum.

Korea is quite good at rom-coms. Consequently they make quite a lot of them and as the standard is comparatively high you have to admire the versatility on offer. Korean romantic comedies are, however, also a little more conservative, coy even, than those from outside of Asia which makes Petty Romance (쩨쩨한 로맨스, Jjae Jjae Han Romaenseu) something of an exception in its desire to veer in a more risqué direction. He’s too introverted, she’s too aggressive – they need each other to take the edges off, it’s a familiar story but one that works quite well. Petty Romance does not attempt to bring anything new to the usual formula but does make the most of its leads’ well honed chemistry whilst keeping the melodrama to a minimum.