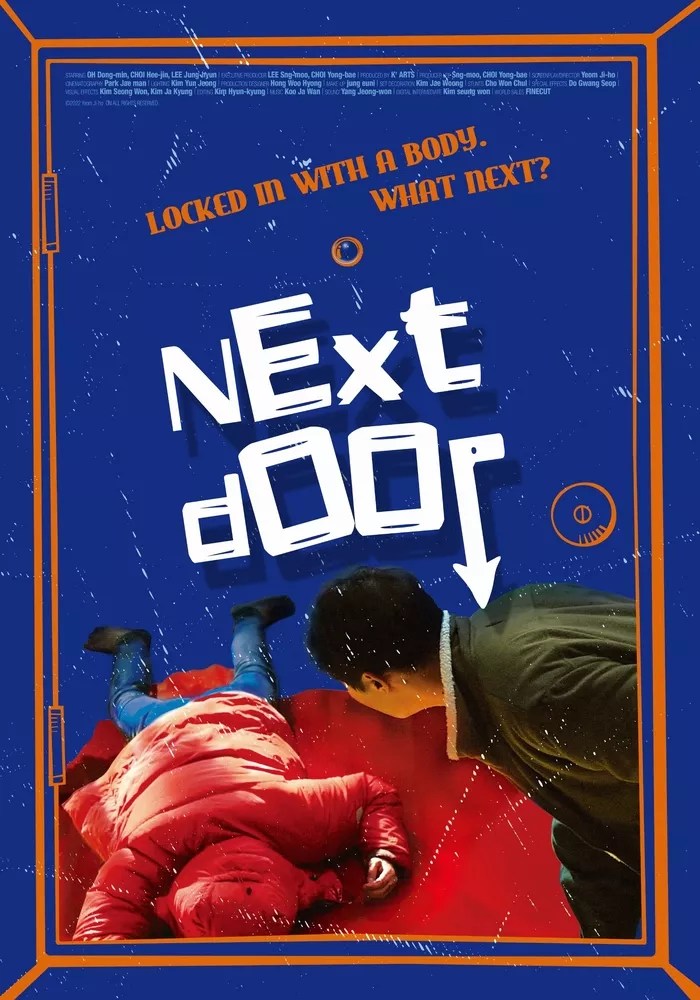

How much do you know about what’s going on with your neighbours? Chan-woo (Oh Dong-min) thinks he knows quite a bit because they never seem to stop arguing and the walls in this building are surprisingly thin, but as it turns out he didn’t really know very much at all nor to be honest did he really care. Yeom Ji-ho’s graduate film Next Door (옆집사람, Yeop Jib Salam) is a tense mystery farce in which an aspiring detective tries to investigate his way out of trouble and somehow ends up coming out on top almost despite himself.

Chan-woo has been unsuccessfully studying for the police exam for the last five years and hopes that his run of miserable failure is about to come to an end, that is as long as he can get himself together to submit the application by 6pm the following day. One of the many problems with that is that Chan-woo has a cashflow problem and there’s not enough in his account to pay the fee so he has to ring a friend who agrees to lend him money but only if he comes out for a drink. Reluctantly agreeing, Chan-woo fails to correct his friends when they assume he’s already passed the test and become a policeman only to get blackout drunk and create some kind of disturbance before waking up in an unfamiliar environment next to what seems to be a corpse surrounded by blood. After a few moments of confusion, Chan-woo realises he must have crawled in next-door in a drunken stupor and returns to his own apartment but discovers that he’s left his phone behind which is inconvenient in itself but especially as it’s now evidence that he was present at a crime scene which won’t look good on his police application form.

To be honest, Chan-woo is not the sharpest knife in the drawer and it’s not until he’s been in the apartment, where he is trapped because the hallway is currently full of religious proselytisers, for some time that he remembers about fingerprints and DNA while deciding to do some investigating to figure out what might have been going on the previous evening. His friend’s messages suggest he has a history of becoming violent and aggressive while drunk and may have gotten into some kind of altercation all of which has him worried that he actually might have been involved in the corpse’s demise.

Meanwhile all he ever did was complain about the noisy woman in 404 who was frequently heard arguing with a man. As an aspiring policeman perhaps he should have checked in on her to make sure she hadn’t become a victim of domestic violence rather than blaming his neighbours for his poor performance. To begin with, he assumes the body must be that of the woman’s boyfriend, but also makes a series of sexist assumptions while looking around the apartment and finding evidence that the person who lived there was a tech wiz immediately assuming that all the computer equipment must belong to the boyfriend. Similarly he decides the girl is probably an airhead after finding photos of her on the corpse’s phone because she is pretty and fashionable. When she finally turns up with bin bags and cleaning supplies, Hyun-min (Choi Hee-jin) first challenges Chan-woo on discovering him hiding in her closet but then changes her tune to appeal to Chan-woo’s vanity playing the helpless young woman looking to him for protection and in effect welding his sexism against him.

His desire to play the hero may be behind his intention to become a police officer but then he’s not exactly a paragon of virtue himself. On discovering the body, we see him raid a piggy bank and pocket a note from the corpse’s wallet to solve his financial problems before thinking better of it and putting everything back where it belongs. He agrees to help Hyun-min deal with the body partly to protect her and partly to protect himself from his proximity to the crime all while trying to make sure he gets back to his own apartment to send the application form before the deadline. Even the landlady eventually offers him a discount on his rent in return for keeping quiet so the murder in the building won’t affect her business. “They were terrible people” he tells her when she repeats a rumour that Hyun-min got into a fight with a jealous boyfriend over money which might not be completely unfair even though he knows the rumour isn’t true and is not entirely blameless himself. A masterclass in blocking and production design, Yeom’s deliciously dark farce suggests it might be worth keeping a better eye on your neighbours in all senses of the term.

Next Door screened as part of this year’s Fantasia International Film Festival.

International trailer (English subtitles)