“What should I do with my life?”, the question becomes a frequent refrain in Mitsuo Yanagimachi’s dark tale of urban alienation, The Nineteen-year-old’s Map (十九歳の地図, Jukyusai no Chizu). Adapted from a novel by Kenji Nakagami which painted a bleak picture life on the margins of the economic miracle, the film’s quiet sense of unease hints at a coming explosion but also that there will never be one because in the end the hero is too filled with despair and ennui to ever follow through on the various threats he makes during a series of prank calls to people in the neighbourhood who’ve incurred his wrath.

The nineteen-year-old of the title, Yoshioka (Yuji Honma) is in theory a student taking a year out to study for university exams while earning his keep delivering papers for a newsagent where he lives in a dorm with several other paperboys all just as defeated and aimless as he is. They all, however, look down on and make fun of him for being a bit odd not least because he hangs around with a 30-year-old man who is still stuck living a like a teenager that the other guys think is creepy. Konno (Kanie Keizo) is creepy in a way, in that he’s an obvious image of what these boys might be in 10 years’ time if they do not manage to find something that will allow them to move forward, out of the slums and into a more fulfilling life.

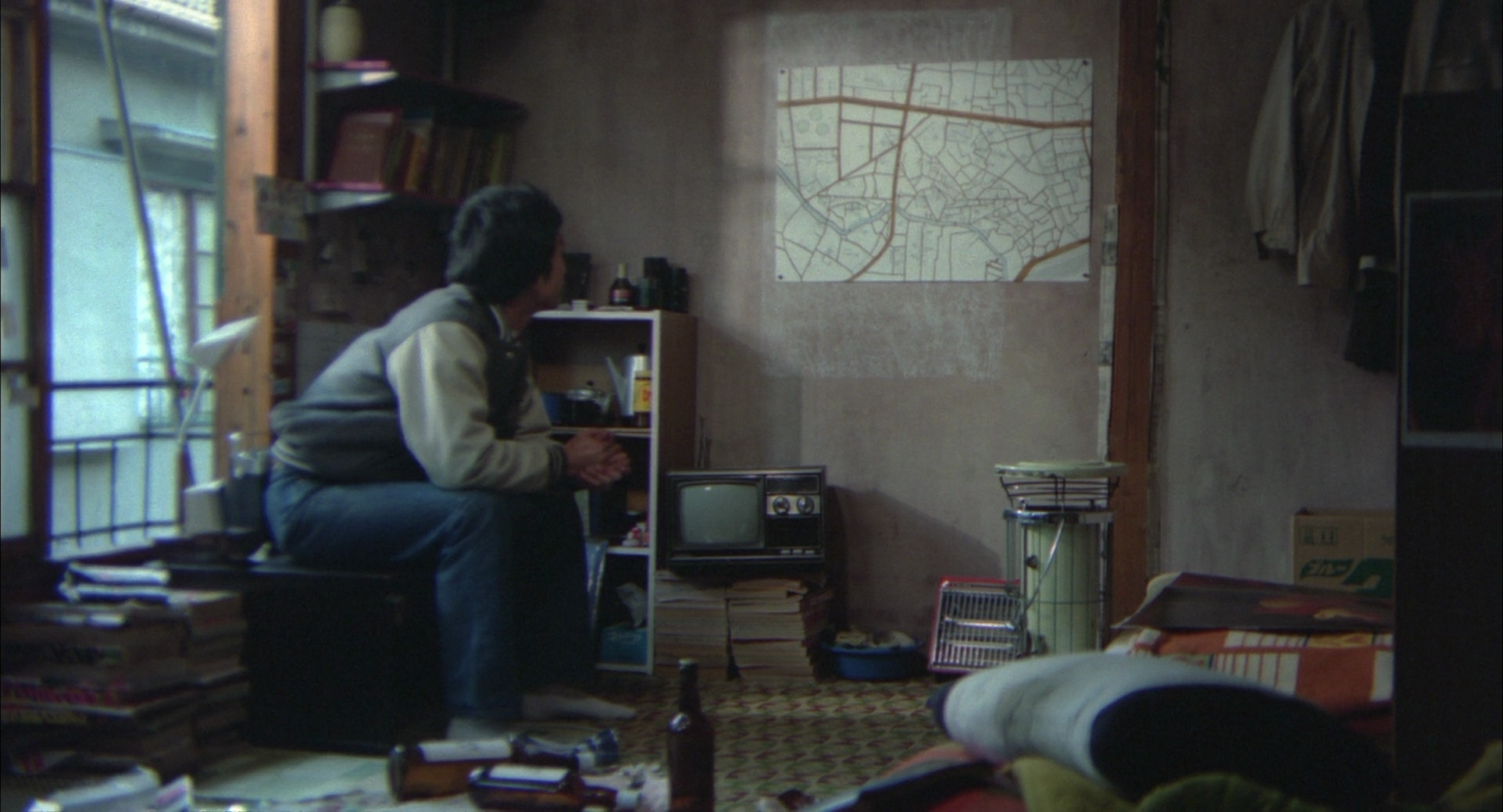

Yoshioka’s main outlet is making a map of the local area which he annotates with notes about the various people who live there, many of them on his paper round. If they do something to displease him or otherwise display something he regards as a moral failing he puts a large cross against their name, and when someone has three crosses he makes a harassing phone call threatening to burn down their house. It’s never quite clear whether his threats have any serious intent or if the threat itself is enough in allowing him to feel powerful and superior to world around him which he feels is rotten beyond repair. People often ask him where he’s from and he tells them but with slight hesitation, as if he’s not telling the entirety of the truth as perhaps confirmed by one woman’s attempt to probe his origins surprised that he doesn’t have any kind of rural accent while she’d never heard of the town he claimed to be from.

One of the other boys at the newspaper office is an aspiring boxer, but he gets badly beaten in a fight and eventually leaves to join the Self Defence Forces. The meanest of them, Sato, has a sharp tongue but seemingly no more direction than Yoshioka finding his release through more direct forms of violence and hateful behaviour. Everyone around him is disappointed and filled with despair. Even the lady who runs the newsagent’s reflects on her unsatisfying life and the ruined hopes of her youth in which she dressed in fine kimonos and kept herself nice. Her only comfort is that she “saved a man deserted by his wife” even if she mainly treats him with contempt for his failure to repair the loose nail in the hallway she keeps catching her foot on, or fix the toilet which continually backs up and floods the bathroom.

Yoshioka does seem to be followed around by leaky appliances while everywhere around him is dank and muddy. Konno has one ray of hope in his life in the form of a woman he calls Maria (Hideko Okiyama) who is covered in scars but still she survives. Maria is indeed a Madonna figure, a symbol of scarred purity and human suffering that Konno regards as a kind of salvation. Yet Konno’s attempt to reach her only leads to further ruin as he commits small but increasingly daring acts of crime from bag snatching to burglary to get the money to run away with her only to end up in prison still wondering what it is he should do with his life.

Maria had told them of a dream she had in which hundreds of people emerged from her and went happily to heaven while she was left on the ground below. Some angels on a cliff tried to lift her up, but she found herself unable to reach out to them only standing immobile and looking up in jealousy. In his way, Yoshioka is much the same perhaps as Konno had said afraid to be happy and unable to envisage for himself a life outside of the slum. Konno sometimes introduces him as a student at a top university which seems to further press on his insecurity. Yoshioka rarely attends classes, spending all his time delivering papers or making his map of iniquity. He describes himself several times as a “right-winger” and at one point fantasises about taking part in a nationalist parade, but aside from his conservative takes on morality seems to have no real ideology save the fact that everyone, even the people who are actually nice to him, pisses him off.

“Even if you’re angry at something, why should you explode the gas tanks?” a telephone operator reasonably asks after Yoshioka makes a prank call reporting a bomb threat on a train leaving Tokyo station while explaining that he also plans to blow up a set of gas cylinders to obliterate the town. The voice on the phone does not appear to take him seriously and sympathetically tries to talk him out of his strange delusion, but all Yoshioka can do is go home and cry in the utter impotence of his life. In the end, Maria is the only one who is able to feel any kind of joy. Finding a pretty dress while dumpster diving, she twirls cheerfully dancing around even with the leg which was left lame after a failed suicide attempt. This time she’s the one who tries to reach out, but Yoshioka ignores her and looks away as they head in different directions. It seems he will never really act on any of his threats, or be able to escape the futility of his life trapped on the margins of a prosperous society which he feels continues to reject him. Yanagimachi films his uneasy existence with naturalist detachment, capturing the mud and filth that cling to Yoshioka along with the strangely violent, goldfish-killing kids, the angry dads, and women who urinate in the street that occupy his round in this particular corner of the “hell” of modern Tokyo.

DVD release trailer (no subtitles)