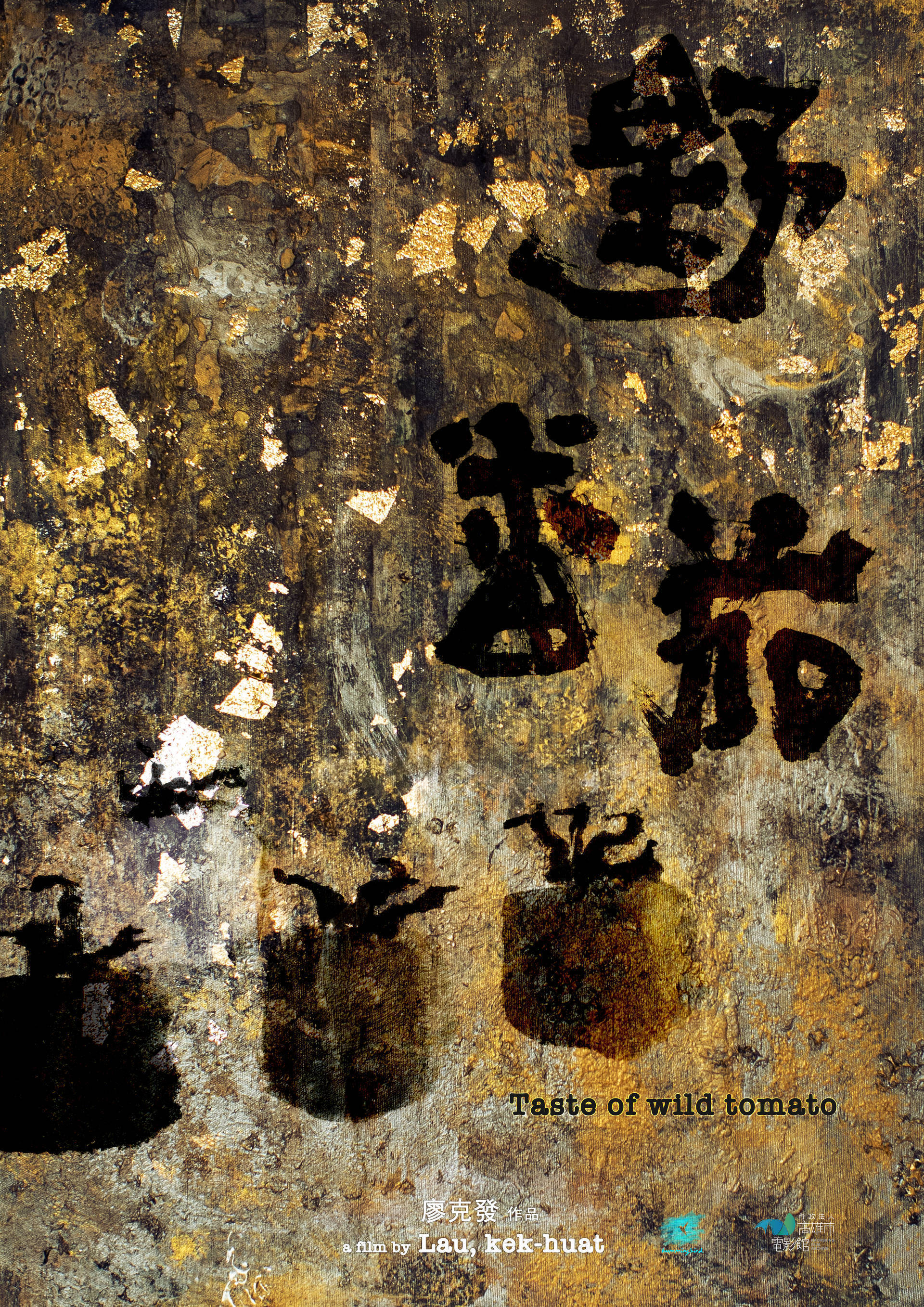

Towards the conclusion of Lau Kek Huat’s documentary Taste of Wild Tomatoes (野番茄, yě fānqié), a man whose father was murdered during the White Terror gets into a heated debate with a supporter of Chiang Kai-shek who asks him if he thinks things would have been better if the Japanese had stayed. It doesn’t seem to occur to her that Taiwan might have been just fine on its own, a free and independent nation no longer subject to any particular coloniser. Her attitude reflects the contradictions of the contemporary society still trying to understand and make peace with its past. The now middle-aged man thinks that Chiang Kai-shek’s presence in “Liberty Square” is inappropriate, “worshipped by tourists who do not know our history”, and that the lingering national trauma of the 228 Incident, in which a popular uprising against the rule of the KMT government in 1947 was brutally put down, has never fully been addressed.

Another of Lau’s protagonists also lost her father to the White Terror and her mother to suicide shortly after. It’s her recollections that give the film its bittersweet title as she remembers being taken to her father’s grave as a small child but not knowing what was going on. She didn’t understand why her mother was crying and simply carried on eating some wild tomatoes that were growing near the grave. Their taste has stayed with her all these years as an ironic reminder of the fruits of oppression and the frustrated vitality of the Taiwanese society enduring even during its hardship.

The film opens with a sequence featuring animation and stock footage from the colonial era over which a man gives a speech likening himself to the Japanese folk hero Momotaro and Taiwan to the island of barbarians to which he traveled. Kaohsiung had been an important military base under Japanese colonial rule, integral to imperial expansion to the South. The voice over describes it as an uncivilised land where they do not speak his language, but then emphasises that Taiwan has been transformed by Japanese intervention and is now the pearl of the empire. “As long as you work hard, you can be the true subjects of the Empire of Japan’” he ominously adds.

Under the Japanese, the Taiwanese people were asked to give up their names and language, but they were also asked to do so under the KMT under whose rule Taiwanese Hokkien was actively suppressed in favour of Mainland Mandarin. A folk singer explains that traditional folk singing is tailored to the rhythms of the local language, Mandarin simply does not scan and if she cannot sing in Taiwanese then she cannot sing at all. She offers a caustic retelling of history in her songs reflecting on the 228 incident and the “unreasonable and cruel” rule of the KMT governor Chen Yi. Another man who took part in the uprising explains that the widow and son of a man who died next to him only came to ask how he died decades later because it was not only taboo but dangerous to make any mention of what happened on that day.

Lau’s camera makes an eerie journey into a tunnel built by the Japanese military that was used as an interrogation room during the White Terror. A guide explains that the soundproofing wasn’t present in the colonial era but was added by the KMT so that people couldn’t hear what was going on inside. The woman who had tried to defend Chiang Kai-shek, irritated by the man continuing to speak in Taiwanese and answering him in Mandarin, had not tried to deny that such things had happened only that sometimes it is necessary to do “bad things” to survive much as an elderly conscript had recounted murdering an abusive Japanese officer and eating his flesh while hiding in the Philippine jungle during the war. “Justice always defeats authoritarian regimes” Chiang is heard to say in an incredibly ironic speech in which he also talks of the importance of rehabilitating “those who learned the wrong ideas in the fascist regimes” and making them accept Sun Yat-Sen’s Three Principles of the People (nationalism, democracy, and the peoples’s welfare).

The woman who lost her parents now cares for her older sister who suffers with dementia, she thinks brought on by the hardship she endured because of her orphanhood. Closing with scenes of an air raid shelter repurposed as a children’s park, the film presents an ambivalent message as to how the past has been incorporated into contemporary life. Something good has been made of these relics of the traumatic memories, but in doing so it might also seem that the past itself has been forgotten or overwritten. The man who lost his father and himself went into exile defiantly holds up banners stating that Taiwan is not “Chinese Taipei” while insisting that the statue of Chiang Kai-shek must be removed from Liberty Square if it is to have any meaning, all while the folk singer continues to sing her song in her own language refusing to be silenced even if society does not always want to hear about its painful past.

Taste of Wild Tomato screened as part of this year’s Hong Kong Film Festival UK.

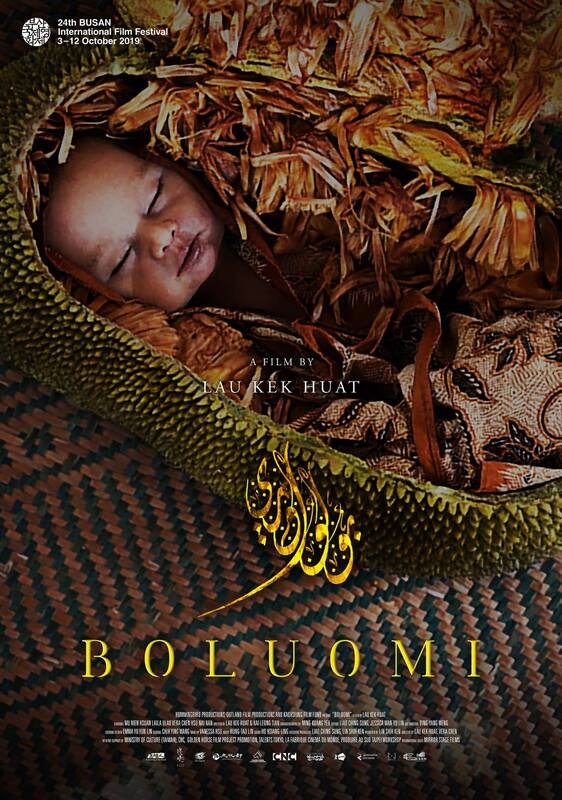

Original trailer (Traditional Chinese / English subtitles)