Shot at the same time as The Love in Okinawa, Sunset Over the Horizon (夕陽西下) is another Okinawan and Taiwanese co-production directed by Lin Fu-ti assumed lost until its discovery in San Francisco’s Chinatown in a Mandarin-dubbed print. Unsurprisingly, it features many of the same cast members and locations and even has a similar theme of impossible love but is more ambitious in scope incorporating both dream sequences and flashbacks to explore the changing relationship between Japan and Taiwan.

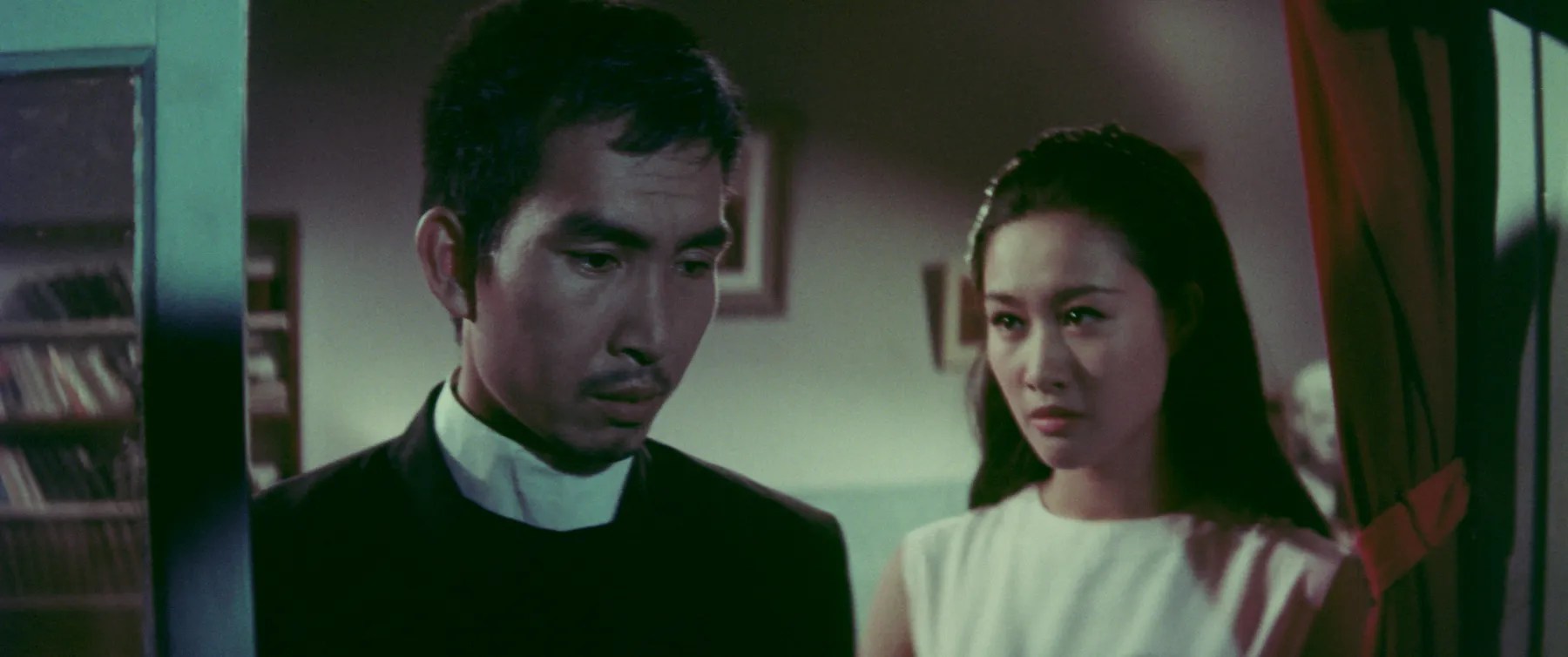

Lin opens the film with its conclusion as Shizuko watches a boat silently depart carrying away her love, the much older pastor/penniless painter Ching-wen who has made the decision to return to Taiwan having finally faced, if not quite come to terms with, his traumatic past at the end of the war and Taiwan’s “liberation” from Japanese colonisation. Japan had conquered Taiwan by force in 1895, but otherwise ruled with much less of an iron fist than it did in other areas of its empire. Lin seems to be making a minor point in dramatising the moment of “liberation” as one of conflicting emotions as the Japanese flag is slowly lowered and that of the KMT, another colonising force, rises in its place meaning that the island is not really “liberated” at all, merely changing hands and to a regime that became more oppressive than that which preceded it had been.

The irony is that it’s this “liberation” that disrupted his romantic future as a young Taiwanese student in love with the daughter of a Japanese general. With the end of the war, the Japanese must leave Taiwan and so his love must go with them and return to the mainland. She asks Ching-wen to come with her, but he refuses. He is unwilling to leave his nation and his family, though we can see he did so years later and traveled to her hometown of Okinawa though she ultimately chose to take her own life out of a sense of despair and futility. She could not return to Japan with Ching-wen nor stay with him in Taiwan either and so to her the only answer, the only real “liberation,” lay in death.

Shizuko later posits something similar even if her dilemma is different. Her businessman father wants her to marry the son of a local factory owner so that he will support his business but Shizuko refuses because she wants to fall in love and does not seem to like her father’s chosen suitor. The situation is somewhat complicated by the fact that Shizuko is a child of her father’s first marriage and is therefore resented by her stepmother who wants her to leave the family as quickly as possible. In some ways this dynastic union represents a decision to embrace the more consumerist future that Japan in the later 1960s represents. Ching-wen on the other hand despite his ruination represents something purer and more spiritual that is less materialistic and rooted in sincere emotion. Shizuko insists that the businessman may buy her body but never her heart, but that seems perfectly fine to him because it seems he’s not all that bothered about her heart and just wants to possess her like a trophy. Frustrated by her objections, he continues to offer greater sums of money and later tells his underling, who looks horrified, that he plans to keep her locked up at home.

But there are other forces which stand in the couple’s way such as the inappropriate 18-year age gap considering that Shizuko is only 19 years old meaning she was born around the time Ching-wen’s first love died (probably at around the same age). It appears that Ching-wen is protestant preacher and so there’s no religious reason why he should not be married, but it’s clear that he has a serious alcohol problem and is a broken, ruined shell of a man unable to bear the romantic heartbreak he endured as a student and has presumably been atoning for ever since. Given all of this, there is no real explanation for the love that exists between them in the first place save for physical attraction (which is less likely given Ching-wen’s unkempt appearance) or a meeting of souls. In the end the theme seems to be moving on from the past and we realise that the lovers cannot be together because Japan and Taiwan must in effect go their separate ways. Though Shizuko too says she longs to return to Taiwan (when she lived there is not explained), she must fulfil her duty to her father by marrying the Japanese businessman. Over the horizon, there is only ever a sunset with no real indication of a happier future in the distance only futility and endurance if also a new beginning in moving on from the traumatic past.

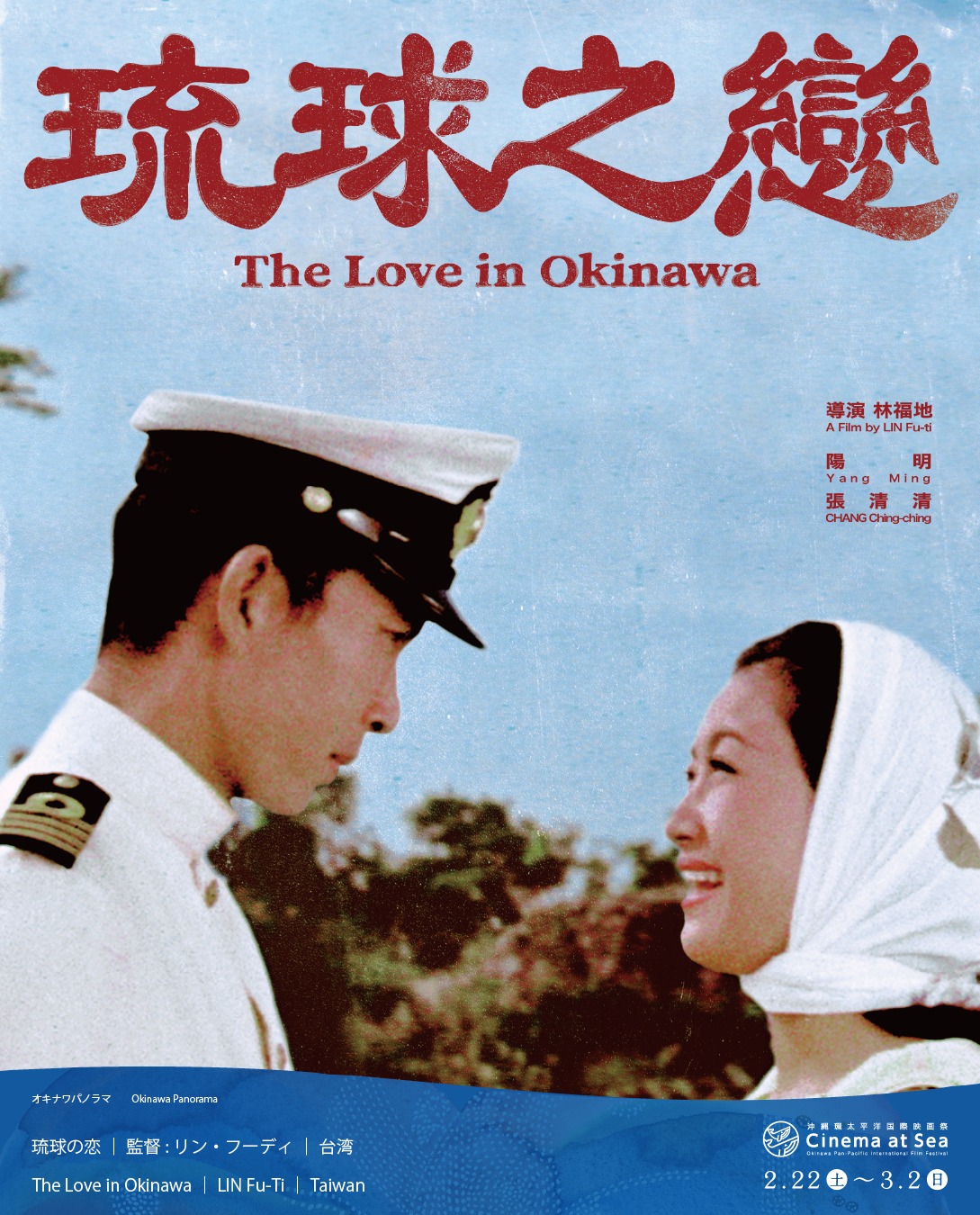

Sunset Over the Horizon screened as part of this year’s Cinema at Sea.

Trailer (English subtitles)