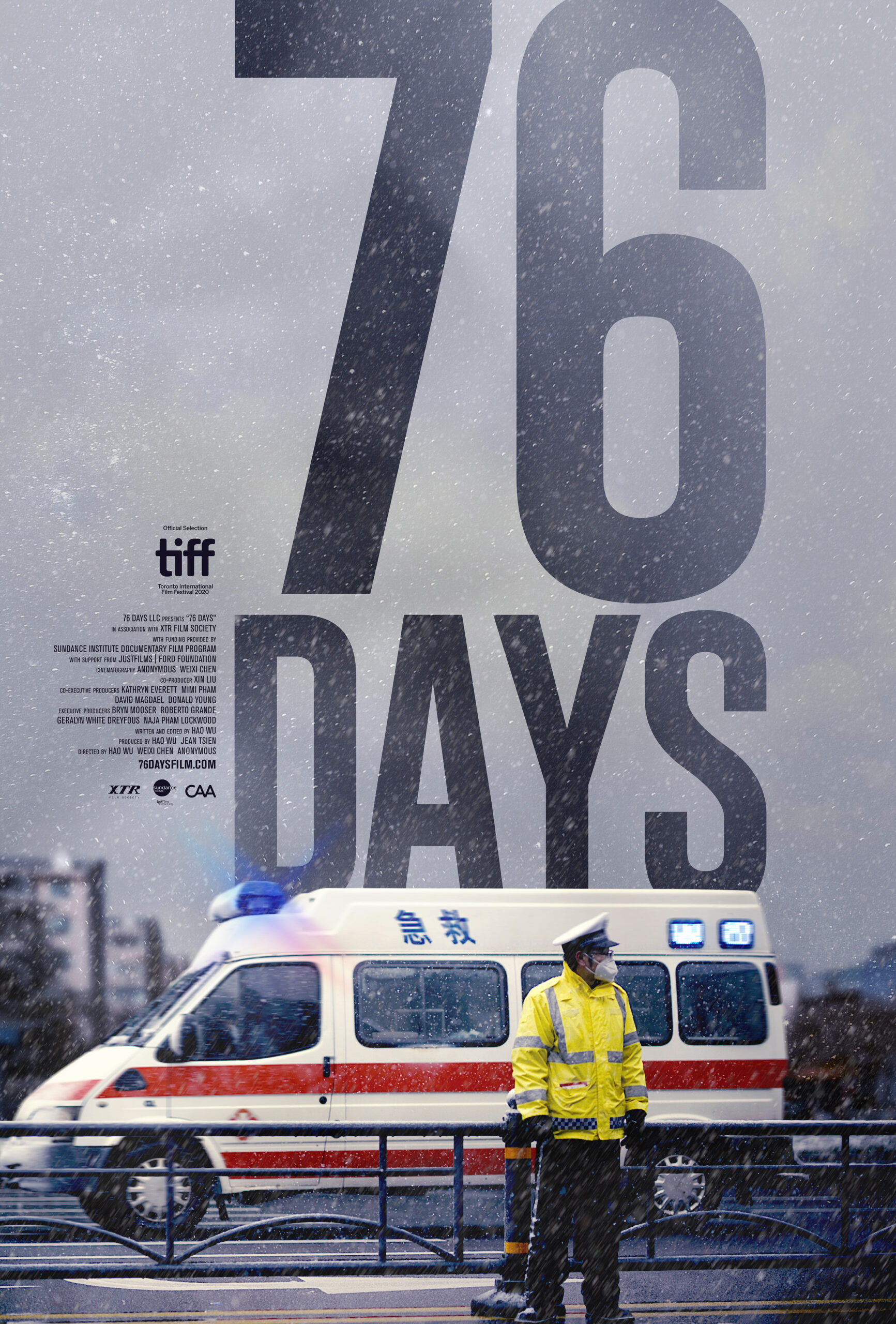

“Don’t worry, so many of us are here for you” a nurse tries to reassure a pregnant woman understandably anxious in being told that her husband cannot be in the room with her while she undergoes an emergency C-section in 76 Days, an observational documentary shot almost entirely within a series of hospitals during the Wuhan lockdown. Co-directed by New York-based director Wu Hao and two on the ground reporters, Chen Weixi and another who has elected to be credited anonymously, 76 Days is testimony to the heroism of the frontline medical personnel who found themselves dealing with a new and mysterious illness, but also a record of a moment as it happened through the eyes of those who were there.

As such, it opens in chaos with a hospital overrun by those who desperately need help and have nowhere else to turn. “Let’s not panic, OK?” the head nurse adds to the end of her briefing as the team prepare for still more patients, many of them waiting in a small room complaining of the cold. Meanwhile, another healthcare worker in a full hazmat suit breaks down in tears not allowed to attend her own dying father while her colleagues try to offer comfort at the same time as encouraging her to pull herself together because they need her on the ward. She can only watch as he’s taken out of the room in an orange bodybag, two of her colleagues continue to take hold of her at the armpits, less for solidarity it seems than to keep her safe while while she follows the gurney down towards the van which will take his body away.

Meanwhile, the doctors attempt to help those who’ve come in looking for treatment including one confused older gentleman who keeps insisting he’s not really ill and wants to go home. Making repeated attempts to escape which might be comical if it were not for the gravity of the situation, the old man is obviously frightened and alone alternating between crying on his bed and wandering around in search of company. Later his son rings him to give him a telling off for causing the doctors so much trouble, reminding him that he’s been a Party Member for decades and ought to be acting with a little more dignity while the doctors do their best to be patient with both men, especially when the son later expresses reluctance to have him back in case he’s not really “cured” (the old man will be one of last to leave the hospital). The old man’s anxiety raises another issue in that he’s used to speaking in dialect and so there is an obvious difficulty in communication between some of the patients, particularly those among the older generation, and the hospital staff some of whom are secondments from Shanghai rather than from the local area. Other patients, meanwhile have been looking up their symptoms on the internet which is causing them additional anxiety and headaches for their doctors who then have to re-explain all their treatment decisions.

We also realise that certain procedures cannot be delayed just because there is so much to do leaving personnel tied up with bureaucracy, often needing to ring grieving relatives to ask them for a copy of their loved ones’ documentation so they can issue a death certificate. Some of the nurses also make a point of rescuing the personal affects of those who’ve died such as bracelets and other items of jewellery so they can be disinfected and returned to family members along with more practical items such as mobile phones and ID cards. At the height of the crisis, there is a large box filled with phones belonging to those who have already passed away some of which are still ringing.

Keeping in touch becomes a secondary problem as couples come in and are shuffled into separate wards, an old woman making regular requests for updates on her husband and a compassionate nurse going so far as to show her his dinner so she can see that he’s eating. Meanwhile the woman who underwent the C-section is isolating away from her baby, she and her husband later enduring another anxious wait towards the end of the lockdown until they’re told that it’s safe for their little girl come home with them. There are no title cards or explanatory text, like everyone else we have no idea where we are or when this will end save for a few brief glances of the daily roster as we notice that admissions seem to be decreasing, people are beginning to go home, and on the momentary glimpses of the outside traffic seems to be increasing on the streets.

Yet even when it’s over it’s not really over. A nurse has to sit and go through that box of phones ringing relatives again, some of whom evidently had not been made aware their loved one had died, to ask them what to do with the affects. The bracelet of one old woman is dutifully returned to her daughter who cannot help crying as she receives it, but like everyone else goes out of her way to thank the doctors for doing all they could while the nurse profusely apologies that they weren’t able to save her. A valuable historical document, 76 Days is also strangely imbued with a kind of hope in the selfless dedication of the doctors and medical staff who daily risked their own lives to save those they could, while proving that this will someday if not exactly end then at least stabilise.

76 Days streamed as part of this year’s San Diego Asian Film Festival.

Clip (English subtitles)