In a way, the 2020 coronavirus pandemic presented a kind of turning point in which it became possible to envision a different kind of future brokered by technological advance in which society was no longer ruled by the dominance of the cities. If people could work remotely from anywhere, then they could easily improve their standard of living by moving to more rural areas for cheaper rents and healthier environments. Assuming the infrastructure was in place to allow them to do so, they could also support and reinvigorate communities struggling with depopulation in which the young have all left for the cities leaving the elderly behind to fend for themselves.

It’s an elegant solution that solves many of the problems of the contemporary society, but change isn’t always as straightforward as it seems as the hero of Yoshiyuki Kishi’s Sunset Sunrise (サンセット・サンライズ) finds out after he jumps at the chance to move into an abandoned house in Tohoku for a fraction of the rent he’d have to pay for a flat in Tokyo if he didn’t still live with his parents. The catch is, however, that houses have souls too and are more than just places to live for those that own or inherit them. Momoka (Mao Inoue), who decides to put her own empty house on the market, has her reasons for not wanting to live there herself nor for selling it completely but renting it out is also emotionally difficult. In the end, she only really does it after being put in charge of the town’s empty house problem at her job working for the council and thinking she should probably start with her own. Not knowing what to charge, it hadn’t really occurred to her someone would be as interested as Shinsaku (Masaki Suda), a fishing enthusiast longing to escape his salaryman life in the city for something a little more traditional in a peaceful rural area.

Then again, that’s not to say that Shinsaku is a traditionalist and his decision quickly sparks controversy but also attracts the attention of his boss who senses a promising business opportunity. Momoka’s is a slightly special case, but Japan is filled with these so-called “akiya” which might, amid the work from home revolution of the pandemic, now be attractive to young professionals looking for a better environment to start a family. Houses generally start to deteriorate quite quickly when no one lives in them, and it’s true a lot of them need some work doing but it’s an idea that could work out well for everyone. Younger people who can’t find decent living space in the cities would be able to afford larger homes in the country where they would also then be contributing and integrating into the local community to provide support for its elderly residents.

Shinsaku becomes a part of the local community quite quickly and strikes up a friendship with an elderly woman whose children have all moved to Tokyo and rarely visit now that their own children are getting older. They’ve asked her to move to Tokyo with them, but as she points out, it would be the same as them moving back. There’s nothing for her to do there, and she’d have no friends. She’d only feel in the way and that she was getting under her daughter-in-law’s feet. Nevertheless, they fear for her especially as the area is still dealing with the scars of the 2011 earthquake which have left many clinging to a now bygone past. Once Momoka and Shinsaku start working with his boss on the akiya project, they find it hard to convince the inheritors of the houses to agree. Though they won’t live there, they might want to pop back a few times a year just for the memories and somehow can’t bear to part with their childhood or relative’s homes. But Shinsaku points out, it doesn’t necessarily have to be a case of either or and the renovation projects they undertake modernise the houses in a sympathetic way that brings them up to date with modern living yet honours the past even sometimes incorporating some of the previous resident’s furniture and belongings while issuing a caveat that the owners are welcome to visit should they wish to.

Essentially, the idea is a kind of co-existence with the past but also with unresolved trauma such as that presented by the earthquake and the ongoing pandemic. Momoka too is struggling to move on and while a gradual romance seems to arise between herself and Shinsaku, she isn’t sure she can ever let the past go though he makes it clear it’s okay to bring it with her. For his part, despite the initial fears of the early pandemic period and the suspicion of him as an outsider, Shinsaku’s quickly taken in by the community and adapts to a more rural way of life with relative ease though his boss’ big plan is rather undermined by his later insistence that he come back to Tokyo to run the project from the office like a many a contemporary CEO rolling back promises of flexible working environments that make this kind of utopian ideal much harder to materialise. In any case, there’s something quite refreshening in the eventual resolution just to do their own thing, not particularly paying attention to labels or what other people might think, but just doing what makes them happy right now. As an old fisherman’s song says, the sun sets but then it rises again. Scripted by Kankuro Kudo and adapted from a novel by Shuhei Nire, the film has kind of wholesome optimism that is rooted in a sense of continuity but also the potential to start again and make a new life inside the old that is less bound by outdated social norms than brokered by the gentle solidarity between people and a generosity of spirit that allows all to seek happiness in whatever way they choose.

Sunset Sunrise screens in Chicago 22nd March as part of the 19th edition of Asian Pop-Up Cinema.

Trailer (English subtitles)

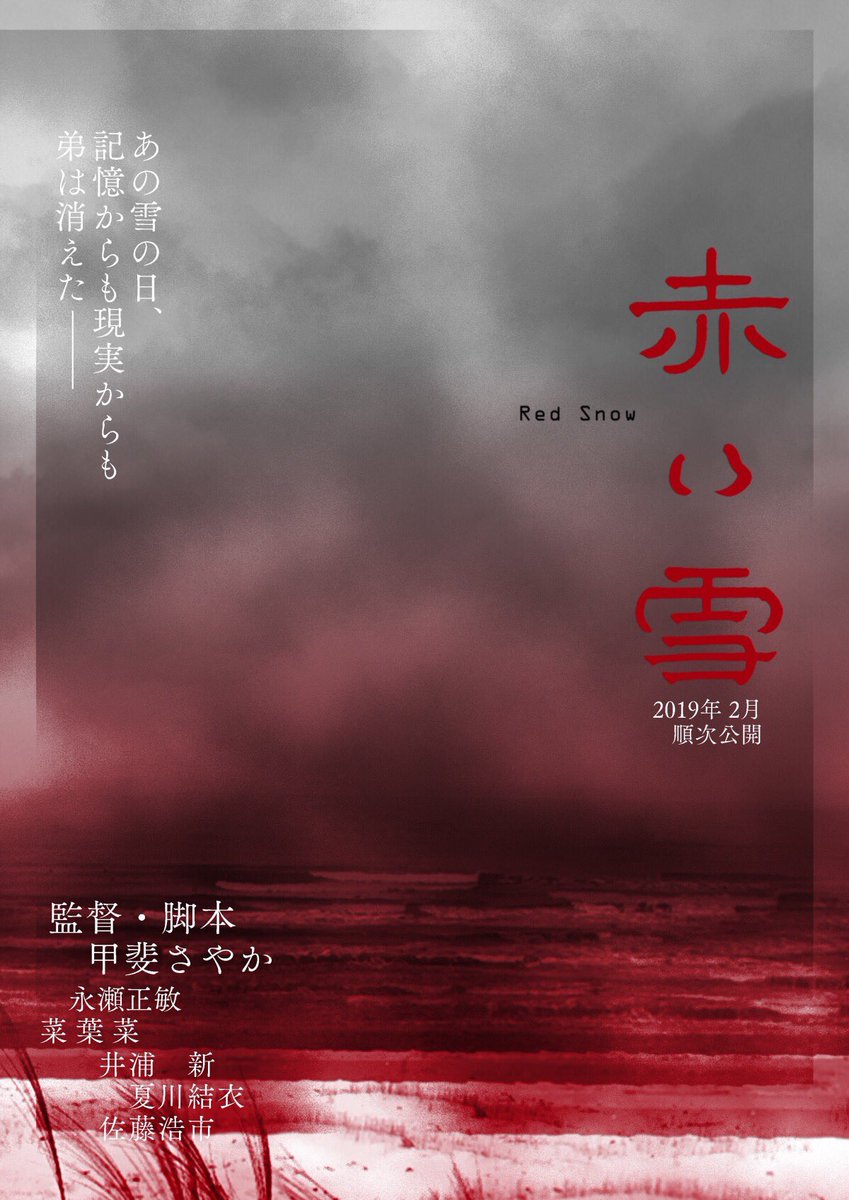

“We’re just pieces of a puzzle” a temporarily deranged woman exclaims to a gloomy seeker after truth in Sayaka Kai’s eerie debut Red Snow (赤い雪, Akai Yuki). Truth, as it turns out is an elusive concept for these variously troubled souls trapped in a purgatorial tailspin on their gloomy island home. When a stranger comes to town intent on unearthing the long buried past, he stirs up deeply repressed emotion and barely concealed anger but finds himself floundering in the maddening snows of a possibly imaginary coastal village.

“We’re just pieces of a puzzle” a temporarily deranged woman exclaims to a gloomy seeker after truth in Sayaka Kai’s eerie debut Red Snow (赤い雪, Akai Yuki). Truth, as it turns out is an elusive concept for these variously troubled souls trapped in a purgatorial tailspin on their gloomy island home. When a stranger comes to town intent on unearthing the long buried past, he stirs up deeply repressed emotion and barely concealed anger but finds himself floundering in the maddening snows of a possibly imaginary coastal village.