Three years after taking down illegal arms dealers, “Interpol” agent Andrew Hoshino (Akira Takarada) returns with another globetrotting adventure, this time concerning a missing coin worth a great deal to an amoral gold smuggler. Ironfinger had appeared in the midst of Bond-mania and boasted a script by none other than Kichachi Okamoto which was full of cartoonish fun and surreal humour as Andy made use of a series of spy gadgets to aid him in his cause. The similarly Bond-referencing sequel, Golden Eyes (100発100中 黄金の眼, Hyappatsu Hyakuchu: Ogon no Me) , attempts something much the same but perhaps without so much of Okamoto’s trademark sophisticated silliness.

This time the action opens in Beirut where a chauffeur is being hunted by a man in a helicopter as he attempts to escape through the sand dunes. Skewered by a giant grappling hook, the driver’s body is apparently then deposited on the roof of a hotel, causing not a little embarrassment to gold smuggling kingpin Stonefeller (see what they did there?) who is already quite worried about attracting the attention of the local police. Meanwhile, Andy happens to be in Beirut on another “vacation”, having fun driving the owner of a shooting game in an arcade out of his mind before he runs into a little girl who tells him that she’s looking for an assassin to avenge the death of her father, the body deposited on the hotel roof. All she can afford to pay him is the silver dollar her dad gave her as a keepsake before he died, but it’s good enough for the kindhearted Andy who decides to get justice for the little girl no matter what. Just then, however, an attempt is made on his life by means of a bomb hidden in a bouquet given to him by pretty Japanese singer Mitsuko (Tomomi Sawa) who is in Beirut to find wealthy men to finance her love of rally car racing.

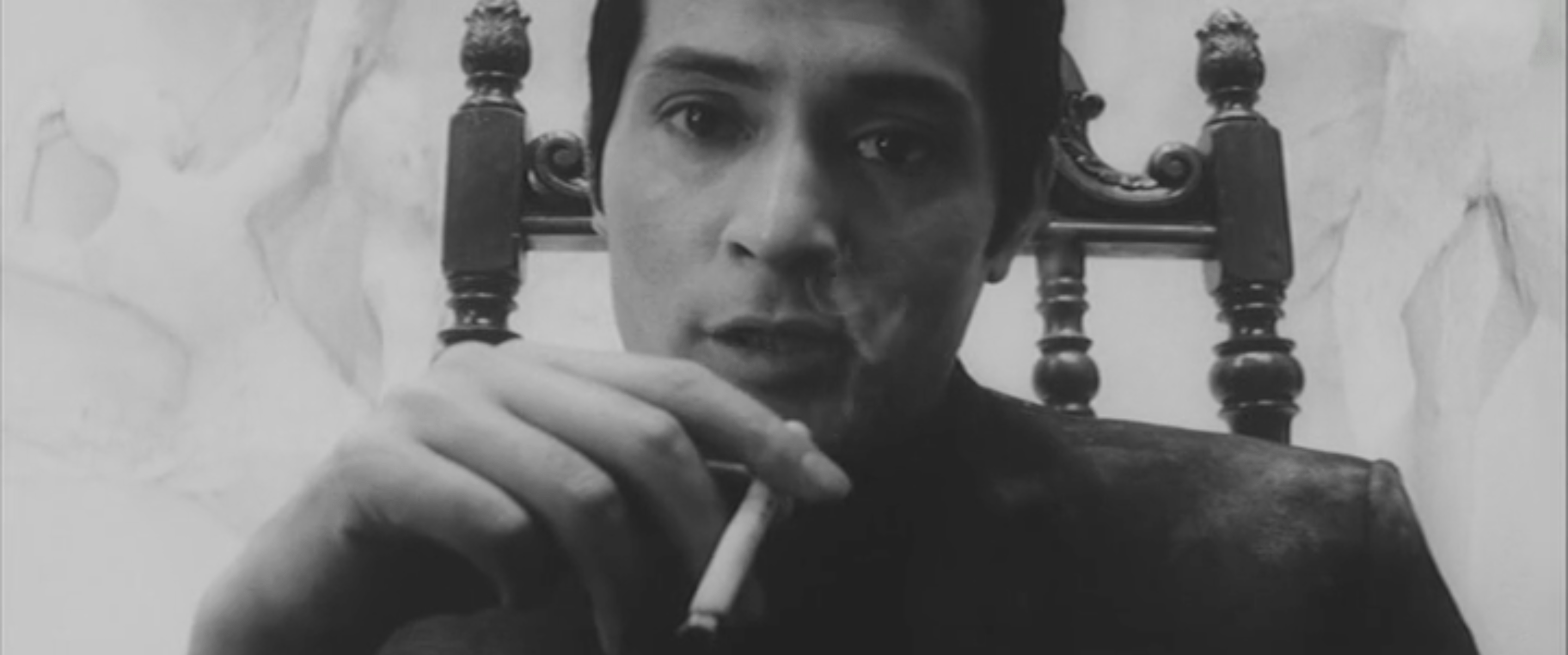

The major antagonist is an ancient American “industrialist” with a dog called Sinbad who thinks that the gold must flow and that he’s doing a public service delivering it to Japan where its absence only highlights the “backwardness” of the Japanese state. Stonefeller is also blind but an ace sniper thanks to a directional microphone in place of a sight on his rifle. In any case, though Stonefeller is the kingpin, the true “villain” is Kurokawa (Yoshio Tsuchiya) who is responsible for the death of the little girl’s father, killed while thought to be in possession of the missing gold coin. The coin later makes villains of the two Beiruti gangsters working with Stonefeller who end up chasing after Kurokawa to try and retrieve it while Andy, mysterious “reporter” Ruby (Bibari Maeda), and earnest detective Tezuka (Makoto Sato) do their best to stop them.

The international villainy may reflect a certain anxiety about Japan’s increasingly global role, rising economy prosperity, and relationship with the Americans, but it’s also a little guilty of exoticisation in its Middle Eastern setting with the majority of Beiruties played by Japanese actors in awkward brown face. An early, spectacular set piece sees Andy and Tezuka beset by Stonefeller’s goons swarming over the dunes dressed as mothers pushing prams which turn out to be fitted with machine guns while Andy sets up a complex stunt which sets off two abandoned weapons with a single pistol shot to take down the bad guys.

Mitsuko, meanwhile, seems to be a symbol of out of control celebrity, an aspiring singer taking part in rally races sponsored by the Japan Economic Council dedicated to fuel efficiency. She is content to be discovered with a dead body because of all the free publicity it’s about to buy her, but more than holds her own when in a difficult situation with the amoral Kurokawa, perhaps a representative of unbridled capitalist greed. Almost blown up with flowers, encased in plaster like a giant mummy, and delivered poisoned gas by room service, Andy maintains an ambiguous cool while still making constant references to his dear French mama waiting for him at home in Paris. As expected, no one except for Tezuka has been quite honest about their intentions or identities, but it hardly seems to matter as they work together while pursuing their own angles to get their hands on the coin and stop the Stonefellers of the world messing around in their economy.