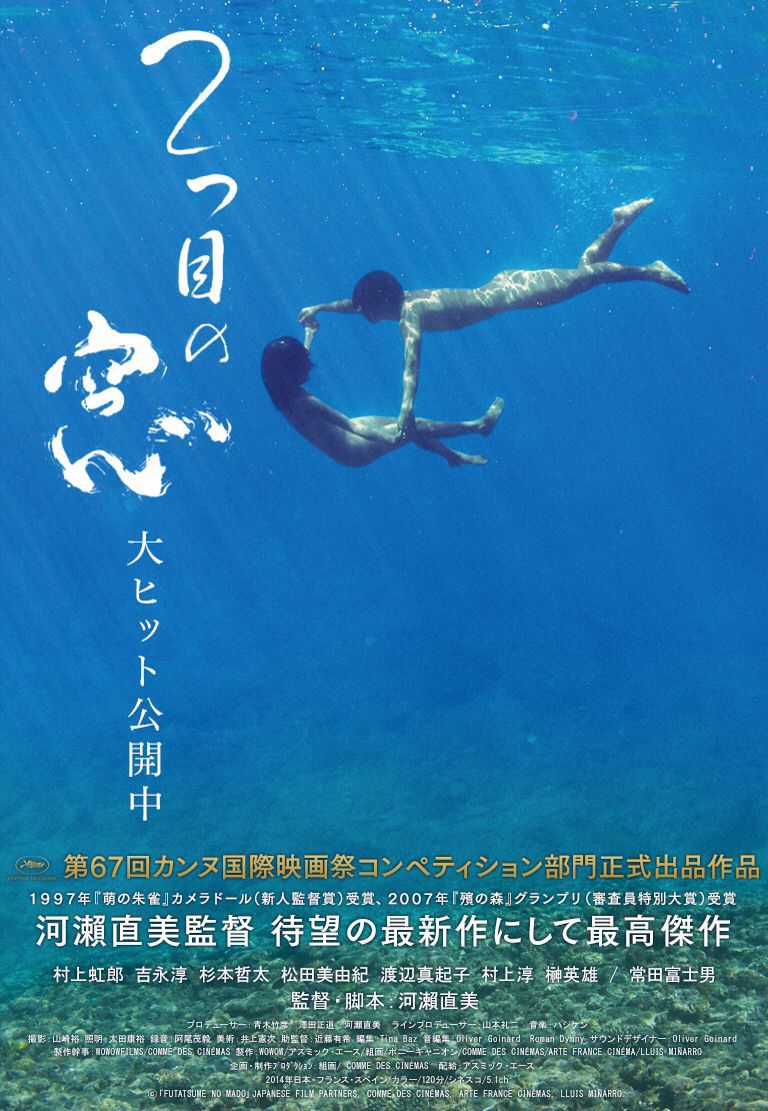

“Why is it that people are born and die?” asks the heroine of Naomi Kawase’s existential odyssey Still the Water (2つ目の窓, Futatsume no Mado). It’s a question with which the director has long been wrestling, though this time more directly as her adolescent protagonists ponder life’s big questions as they prepare to come of age. Moving away from the verdant forests of Nara Prefecture with which her work is most closely associated, Kawase shifts to the tropical beaches of Amami Oshima, a small island somewhere between Kyushu and Okinawa as two youngsters discover life and death on the shore while contemplating what lies beneath the sea.

Opening with rolling waves and the graphic death of a goat, Kawase’s trademark visions of nature soon give way to night and the discovery of a tattooed man washed up on the shore made by moody teen Kaito (Nijiro Murakami) who leaves abruptly, walking past the confused figure of his tentative love interest Kyoko (Jun Yoshinaga) with whom he was supposed to meet. The next morning the townspeople are all aflutter with news of the body, confused by the sight seeing as there are few crimes in this community but admittedly many accidents. The cause of death however is an irrelevance, the import is in the body and what it represents.

First and foremost, it turns the ocean into an active “crime” scene, placed off limits to the locals but Kyoko, a bold and precocious young woman, dives right in in her school uniform and all merely laughing as Kaito remains on the jetty asking her if she isn’t afraid. Raised in they city, Kaito finds the sea disquieting, apparently squeamish of its “stickiness”, describing it as something “alive” only for the bemused Kyoko to point out that she is a living thing too, exposing his essential fear of her as she kisses him and he freezes. On the brink of adulthood, Kaito is afraid to live, afraid of the “death” that change represents, and most of all afraid of the sea inside in the infinite confusion of human feeling.

That confusion spills over into animosity towards his mother, Misaki (Makiko Watanabe), who, obviously at a different stage of life, exists in a world inaccessible to him. He’s at school during the day while she works evenings at a restaurant so they are rarely together and he’s quietly resentful on coming to the realisation that his mother is also a woman, berating her for daring to have a sex life and flying to Tokyo to attempt a man-to-man conversation with his absent father to figure out why their marriage failed. His dad, however, spins him some poetic lines about fate and romance which don’t really explain anything, paradoxically affirming that he feels more connected to Misaki now that they’re apart while admitting that age has shown him “fate” is less soaring emotion and more an expression of something which endures.

Kyoko meanwhile is considering something much the same as she tries to come to terms with her shaman mother’s terminal illness, reassured by another priest that although her mother’s body will leave this world her warmth will survive. She and Kaito are treated to a lesson in nature red in tooth and claw as an old man slits the throat of a goat while the pair of them watch something die. “How long will it take?” Kaito asks in irritation, while Kyoko looks on intently until finally exclaiming that “the spirit has left”. Later she is forced to watch as her mother dies but even on her deathbed is painfully full of life, listening to plaintive traditional folksongs and moving her arms in motion with the music as the others dance.

The old man, Kame, tells the youngsters that as young people they should live life to the full without regret, do what they want to do, say what they want to say, cry when they want to cry, and leave it to the old folks to pick up the pieces. But he also admonishes them for not yet understanding what lies in the sea. It’s Toru, Kyoko’s equally new age father, who eventually talks Kaito out of his fear which is in reality a fear of life, explaining that the ocean is great and terrible swallowing many things but that when he surfs it’s akin to becoming one with that energy and achieving finally a moment of complete stillness. Kaito needs to learn to “still the water”, to bear the “stickiness” of being alive to enjoy its transient rewards while the far more active Kyoko finds solace in her mother’s words that they are each part of a great chain of womanhood which is in itself endless, something Kame also hints at in mistaking the figure of Kyoko walking on the sand for that of her long departed great grandmother.

Nature eventually takes its course and in the most beautiful of ways as the young lovers learn to swim in the sea in spite of whatever it is that might be lurking under the surface. Death and life, joy and fear and misery, the sea holds all of these and more but they roll in and out like waves hitting the shore and the key it seems is learning to find the stillness amid the chaos in which there lies its own kind of eternity.

Trailer (English subtitles)